Will Bangladesh’s Asean dream become a reality?

The path to joining the bloc is long and complex, requiring sustained political will and a resolution to the ongoing Rohingya crisis

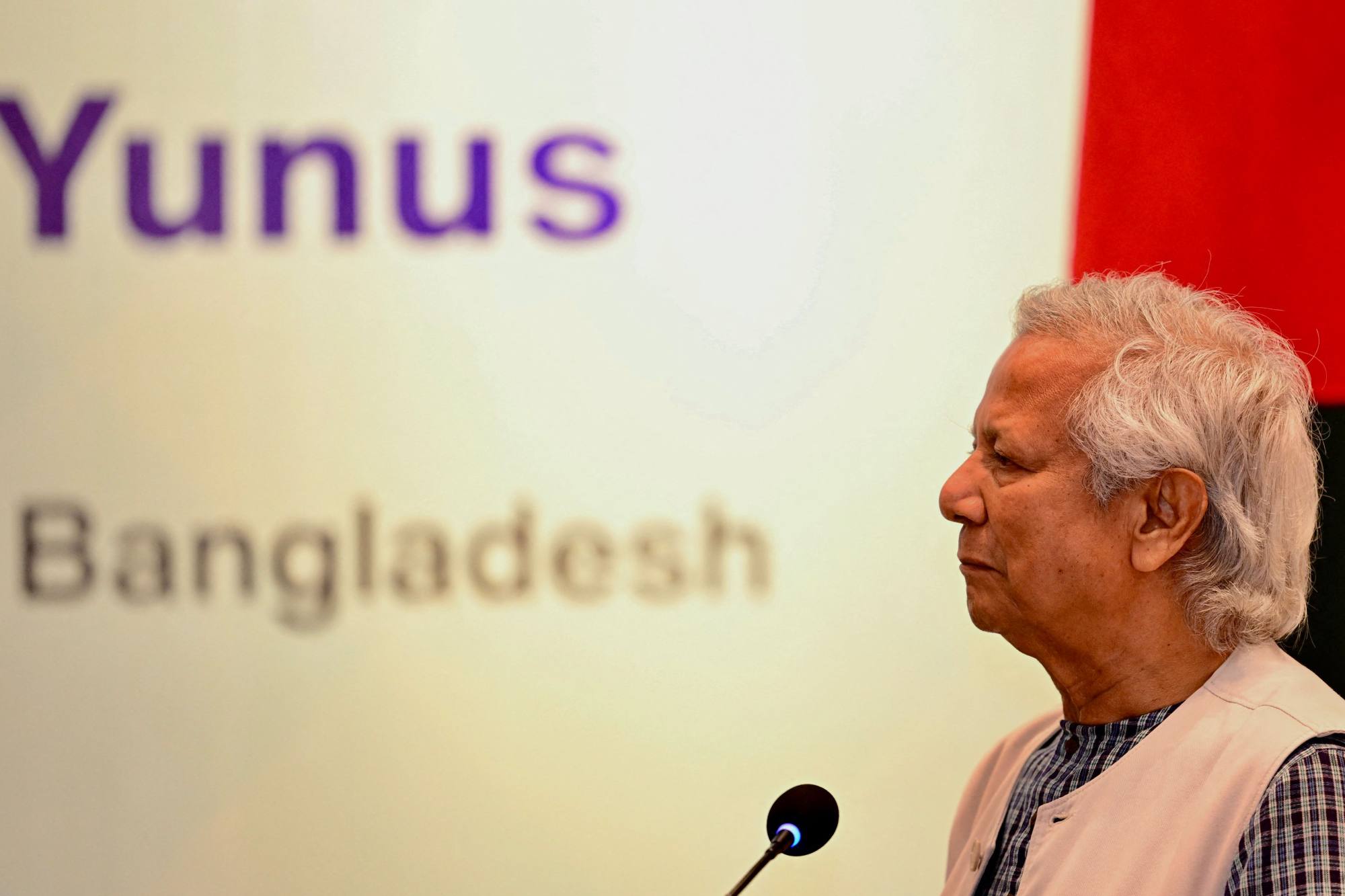

Bangladesh’s renewed quest for Asean membership comes at a moment of acute internal flux and regional scepticism, as interim leader Muhammad Yunus looks to Malaysia for support but finds the path to entry blocked by questions over governance and stability.

On Sunday, he revived his country’s call for Malaysia’s backing to secure a place among the ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

According to his office, Yunus met with Nurul Izzah, daughter of Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim and vice-president of the People’s Justice Party, telling her: “We want to become a part of Asean, and we will be needing your support.”

As current Asean chair, Malaysia is positioned to play a key role in advancing Bangladesh’s application to become a sectoral dialogue partner – a preliminary step towards eventual full membership.

Dhaka first applied for this status in 2020, which is extended to countries engaging with at least two of Asean’s sectors, such as trade, economics, and science and technology.

The road ahead is steep, however. Bangladesh faces “significant” challenges to joining, according to Doris Liew, an economist specialising in Southeast Asian development. Full membership or even observer status, she warned, would require “sustained political will, extensive negotiations and overcoming administrative hurdles”, with the current momentum driven primarily by Yunus himself.

“Whether this initiative will endure beyond his term is uncertain,” Liew said. For Bangladesh’s bid to be “taken seriously”, she argued, Dhaka must ensure a stable leadership transition, display coherent policy direction, and achieve domestic stability.

With “lingering instability in Myanmar”, Asean was likely to proceed cautiously when considering new members with potential governance risks, she added.

The case of East Timor highlights the potential for lengthy delays. Dili applied for membership in 2011, secured observer status only in 2022, and still awaits full accession. “Bangladesh’s bid is likely to face a similarly long and complex process,” Liew said.

Bangladesh has been under an unelected interim government led by Yunus since August last year, after a wave of student-led protests ousted former prime minister Sheikh Hasina. The country’s main opposition party has cautioned that instability and public “resentment” may intensify if elections – postponed by Yunus until 2026 – are not held by December.

Malaysia’s support for Dhaka’s Asean bid remains equivocal. “Discussions are expected to take time,” Liew said, pointing out that Malaysia had yet to prioritise Bangladesh’s membership on this year’s Asean agenda and would soon hand over the chairmanship to the Philippines.

“Bangladesh had also sought support from the Philippines back in March, but progress has remained muted,” she added.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

Md Obaidullah, a visiting scholar at Daffodil International University in Dhaka, said that Malaysia’s support was influential, but stressed that because all 10 member states must agree on membership, “potential resistance, particularly from Myanmar, could pose challenges”.

“Still, Malaysia’s leadership in 2025 offers the best opportunity yet for Dhaka to make diplomatic headway toward its long-term Asean goal,” he said, adding that Bangladesh must also prove its ability to uphold Asean’s foundational values, including non-interference and commitment to regional conflict resolution.

Myanmar’s opposition to Bangladesh’s bid stems primarily from the ongoing Rohingya crisis, which has seen more than 1 million refugees flee the Southeast Asian nation’s Rakhine state to Bangladesh. Despite Dhaka’s persistent calls for repatriation, Myanmar’s junta, installed after a 2021 coup, has shown little willingness to cooperate while facing allegations of human rights abuses against the Rohingya community.

But analysts agree that Bangladesh’s accession could yield substantial economic dividends, enhancing trade and connectivity both for itself and for Southeast Asia.

According to Liew, Bangladesh’s large pool of STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) graduates and skilled, cost-competitive workforce could help Asean move up the value chain and alleviate the region’s demographic and skills shortages.

“This transition could support stronger regional economic growth and broader development opportunities across Asean,” she said.

Obaidullah highlighted the opportunity for Bangladesh to diversify its exports beyond traditional Western markets, tapping into Asean’s US$4.5 trillion economy and integration into the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. As Bangladesh prepares to graduate from its least developed country status in November 2026, a decline of between 7 and 14 per cent in exports to the European Union and North America is expected.

“Asean could serve as a buffer,” Obaidullah said, with the bloc potentially offering a 17 per cent boost to Bangladesh’s exports.

Integration would also allow Bangladesh to enter regional supply chains in electronics, automotive and advanced manufacturing while attracting greater foreign direct investment.

Bangladesh’s new Matarbari deep-sea port, its first, could further streamline trade flows between Asean and South Asia, reducing reliance on narrow maritime chokepoints such as the Strait of Malacca.

“Asean membership would enhance Bangladesh’s diplomatic profile and reduce over-reliance on major regional powers like India and China,” Obaidullah added.