Why US exceptionalism and the export of crassness are losing shallow appeal

America’s inevitable decline proves that nations thrive by prioritising their needs and working with others, not seeking economic dominance

In early May, as Roman Catholic cardinals convened for their conclave, US President Donald Trump posted an AI-generated image of himself as the pope. Shortly afterwards, he declared that he would like to become a pontiff. Reactions from around the globe were swift, though not everyone was shocked. After all, this was American crassness at its finest – a spectacle the world has grown accustomed to. Trump is neither the first nor the only US figure to inure the world to such behaviour; there is a long list.

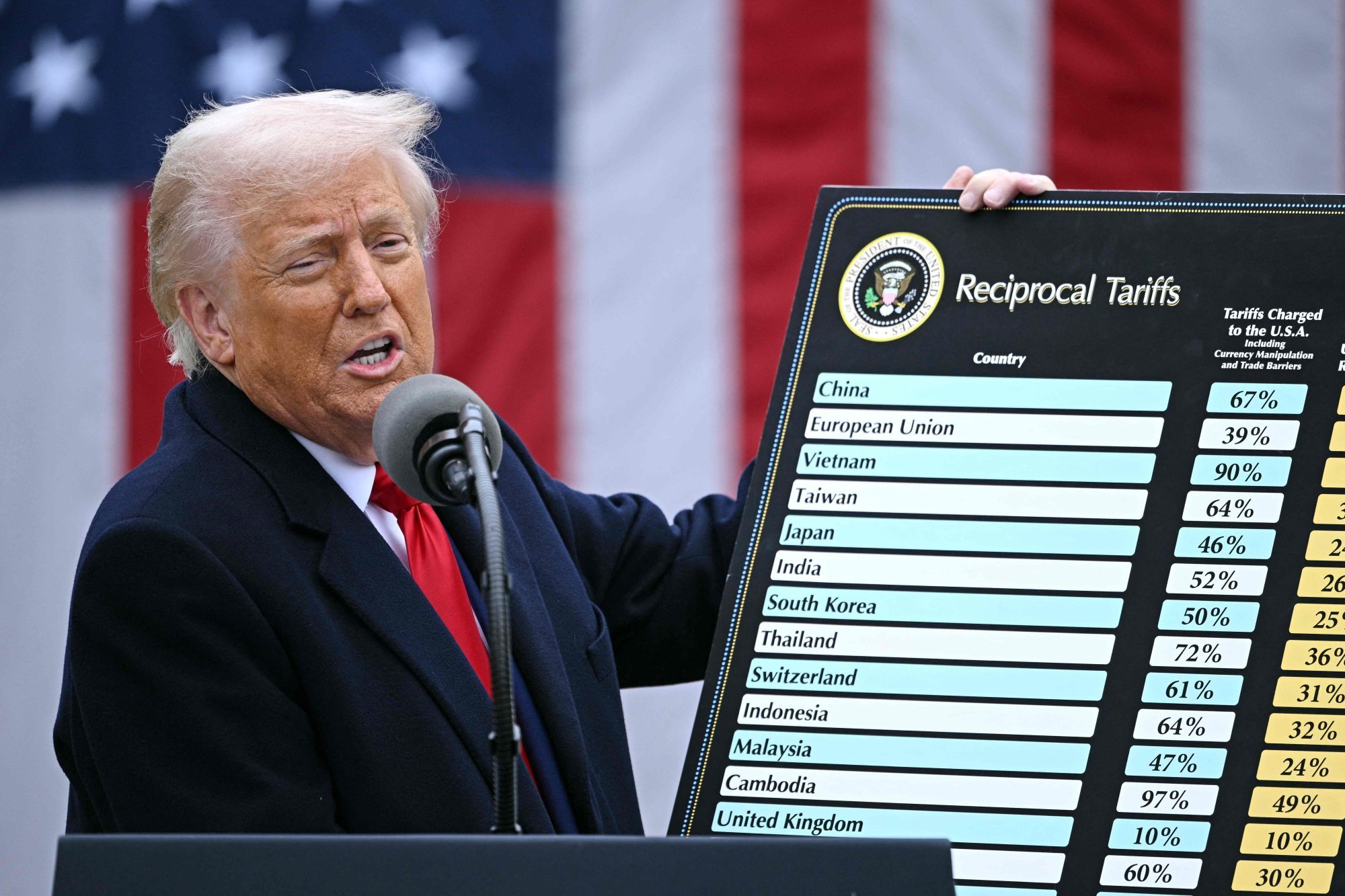

When Trump announced sweeping tariffs on global trading partners in April, with China bearing the brunt, financial markets plunged into their worst turmoil since the early days of the pandemic. Ignorance, arrogance, exceptionalism, and fear of “the other” converged in a display of American crassness on steroids. Trillions of dollars evaporated from stock valuations. Only when the fallout became too severe did Trump pause tariffs for most countries, eventually negotiating with China in mid-May. Yet much of the American public missed the larger picture: these tariffs weren’t about sparking a trade war or addressing claims of the world “ripping off” America. They were a desperate gambit to prop up the American brand – a brand that was sustained for decades by economic hegemony and the “exorbitant privilege” of the dollar, but is now facing its moment of decline.

Desperate to project strength, Trump boasted that world leaders were queuing up to make deals and even “kiss his a**”. To call such behaviour crass would be an understatement, but the world barely blinked. This crude bravado has long been central to the American way, manifesting in entertainment, politics, media, finance and even sports. To much of the world, it reflects the immature culture of a brash young settler nation. Wealth accumulated through the colonisation of Native American lands bred an unfettered arrogance that normalised such behaviour. The world once playfully dubbed this the “Ugly American”, but that playful tolerance only emboldened the American psyche. Today, this has culminated in a rogue state run by supremacists, supported by a large majority.

The US trade deficit, often cited as justification for protectionist tariffs, is merely a symptom of a deeper malaise. The real issue is that American goods – and the culture that sells them – are losing their appeal. Nations like China, South Korea, and before them Japan, now produce superior goods. Meanwhile America, high on its own rhetoric about globalisation, shifted its economy towards services dominated by the financial sector, hollowing out its manufacturing base. Yet Americans continued to borrow and consume at unparalleled levels, encouraged by the state. Living beyond their means, they amassed crippling debt. All the while, they were led to believe that their consumerism was the engine of global growth, a myth perpetuated by American business media like Bloomberg and CNBC. For decades, this propaganda painted American life as the global standard. What was once irresistible now feels unsustainable, replaceable and, to the rest of the world, deeply crass.

The world has finally woken up to the unsustainable mechanisms of the US-led “rules-based order” and the hollowness of the so-called American dream. So why did it take so long for the world to realise that this dream is, in truth, a paper tiger?

The myth of American superiority

The United States has long seen itself as a guiding light for the world – a perception shaped by Puritan self-righteousness and 19th-century expansionist zeal, epitomised by the doctrine of “manifest destiny”. Rooted in Judeo-Christian ideologies and white supremacy, early settlers viewed their arrival in America as a divine mission, fostering a misguided sense of superiority. This was no different from the Calvinist settlers who created apartheid in South Africa. The belief that Americans were divinely ordained to dominate the continent fuelled an unearned sense of entitlement masked as moral duty.

Today, this arrogance persists, even as evidence of American decline mounts. The propaganda that accompanied America’s global expansion – driven by the narrow interests of its business elite – is unparalleled. A world emerging from centuries of colonisation was sold the virtues of crass consumption and exports like junk food and B-movies. But this era is drawing to a close as a multi-polar, post-Western and truly interconnected world emerges.

Consider education, long touted as a pillar of American soft power. Despite 16 industrialised nations outperforming the US in science education and 23 in maths, most Americans still believe their country ranks among the world’s top three. This cultural overconfidence extends far beyond academics, as evidenced in its declining competitiveness, stagnating innovation and an ill-prepared workforce. The media, Hollywood, and Silicon Valley package American life as the global aspirational standard, ignoring its underlying rot: obesity epidemics, opioid crises, gun violence, systemic racism, and a political system that oscillates between dysfunction and spectacle. The “American dream” is aptly named, as one must be asleep to believe it. The world, however, is no longer fooled.

While every nation has its flaws, none have matched America’s shameless promotion of itself as a global benefactor. The US has made contributions to the world, but its unparalleled export of crassness – via junk food, entertainment, and consumerism – has inflicted far-reaching damage across the planet.

In the 20th century, the American empire realised it could no longer rely solely on military might, though the military-industrial complex remains central to its economy. Instead, it wielded its economic power to promote its culture and “soft power”: drive-ins, junk food, B-movies, talk shows and pop music became weapons of cultural domination. Alongside aircraft carriers and Marine divisions came McDonald’s, Coca-Cola and Starbucks.

The Pentagon still earmarks billions for “soft power” projects, subsidising the global saturation of Marvel movies and McNuggets. Hollywood, marketed to the world as a beacon of creativity despite its American-centric biases and naivety, continues to churn out formulaic superhero sequels and unnecessary spectacles, drowning global markets in themes of rugged individualism and machismo.

Meanwhile, brands like Apple, Amazon and Nike, while preaching sustainability, peddle unsustainable consumerism. Social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram, ostensibly designed to connect, have isolated a quarter of humanity in loneliness. The leaders of these corporations, from Mark Zuckerberg to Elon Musk, embody the very isolation and weirdness their products inflict.

This cultural blitzkrieg has deeply embedded American crassness across the globe, from entertainment to finance, processed foods and business schools. Reversing this influence will take decades.

Why the world is walking away

American economic might once bulldozed local traditions, replacing them with homogenised consumer culture. Yet the forces that built its empire now accelerate its decline. China leads in tech, Europe in quality of life, and South Korea in cultural influence, while America clings to tariffs and tired blockbusters like the latest entry in the Mission Impossible franchise. Even foreign-policy blunders such as the wars in Vietnam – and crimes such as the interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan as well as Washington’s support for the genocide in Gaza – show the growing global intolerance for American exceptionalism and bullying.

Rather than engage with the world to negotiate peace in tricky regions its ideological perversions and economic interests always take precedence, and it resorts to force no matter the cost to the world. In the economic arena rather than innovate, the US resorts to blunt instruments like sanctions and tariffs, attempting to mask its fading competitiveness. Its leading tech firms shamelessly lobby for protection from open competition, exposing the hypocrisy of its rhetoric about innovation and commitment to the free market.

Meanwhile, other nations rediscover their unique paths: Sweden’s fika ritual prioritises connection over productivity, and Japan’s culinary traditions value moderation over excess in stark contrast to America’s “gulp and go” and “super-size” everything culture. The world is moving on, and America must do the same, abandoning decades of misguided exceptionalism and embracing humility.

Let its retreat inward, however reluctant, become an unexpected gift – proof that nations thrive not by dominating others, but by fixing their own house first.

If leaders reflect their culture, America’s current crop speaks volumes. Figures like Trump, Musk and Jeff Bezos are products of a system that glorifies wealth accumulation, rewards bombast over substance and idolises celebrity.

Trump’s tariffs and Musk’s Martian fantasies expose a nation that preaches free markets while fearing competition, and denounces empires while building its own. Vice-President J.D. Vance’s dismissal of the Chinese as “peasants” reveals the insecurity beneath America’s swagger.

This unchecked appetite for excess has inflicted grotesque income disparity, an underfunded education system and environmental degradation on an industrial scale. If America doesn’t shed its love and promotion of crassness, it won’t just lose its place at the top of the economic and cultural ladder – it risks combusting under the weight of its own hypocrisy.

Chandran Nair is the founder of the Global Institute for Tomorrow and a member of the Club of Rome. He is also the author of “Dismantling Global White Privilege: Equity for a Post-Western World” and “The Sustainable State: The Future of Government, Economy and Society”.