Why Singapore refused to be a ‘Third China’ – and how Lee Kuan Yew made it clear

In his new book, veteran editor Cheong Yip Seng recalls how Lee Kuan Yew drew a diplomatic line that defined Singapore’s independent path

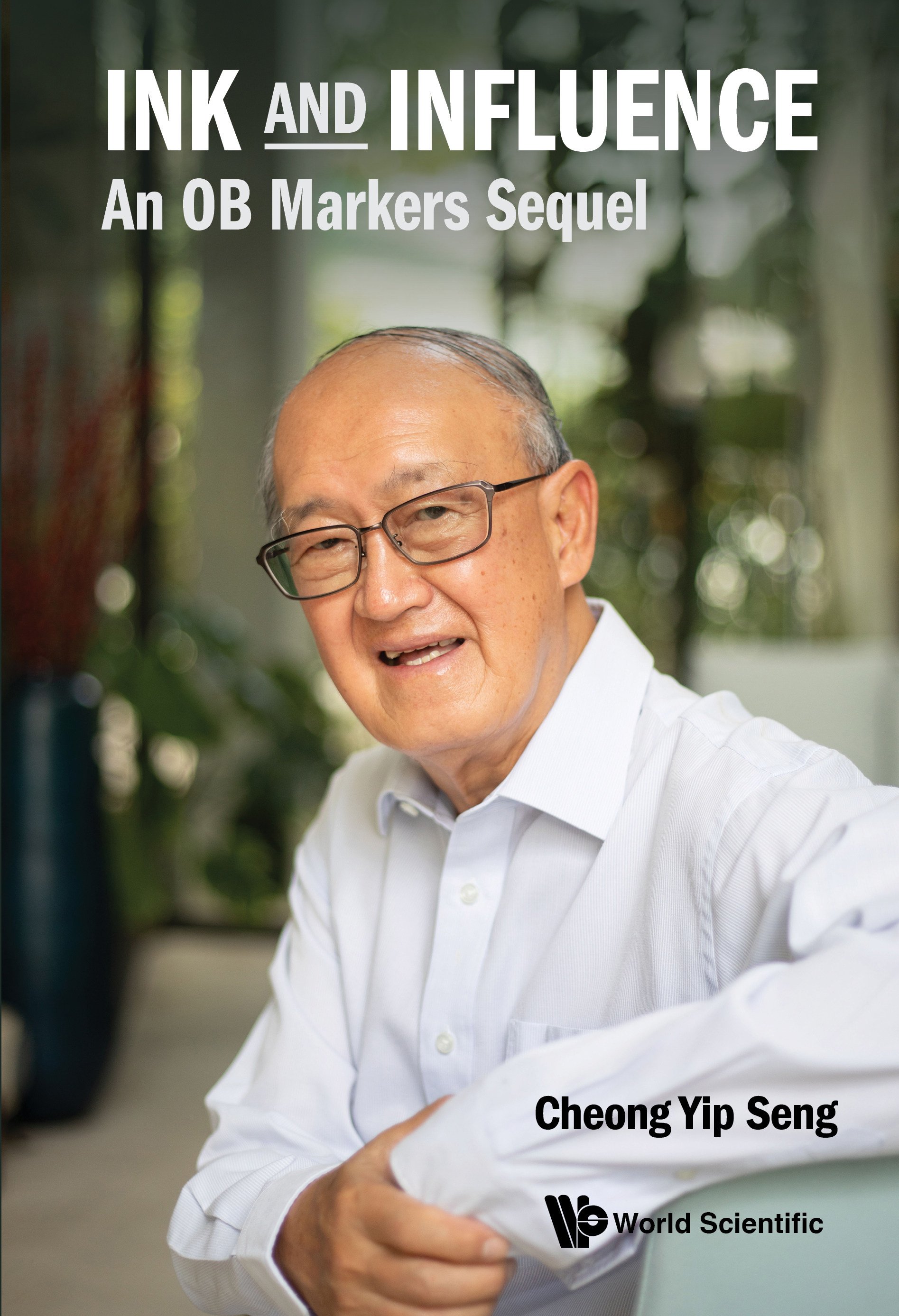

In his new memoir Ink and Influence: An OB Markers Sequel, Cheong Yip Seng reflects on the intersection of geopolitics, media, and identity through the lens of his long career as editor-in-chief of The Straits Times. In this excerpt, Cheong recounts a revealing moment during an official visit to China in 1976 with then-prime minister Lee Kuan Yew. Among the officials present was S.R. Nathan, later Singapore’s sixth president, who witnessed Lee subtly rebuff a Chinese attempt to influence the city state’s foreign alignment.

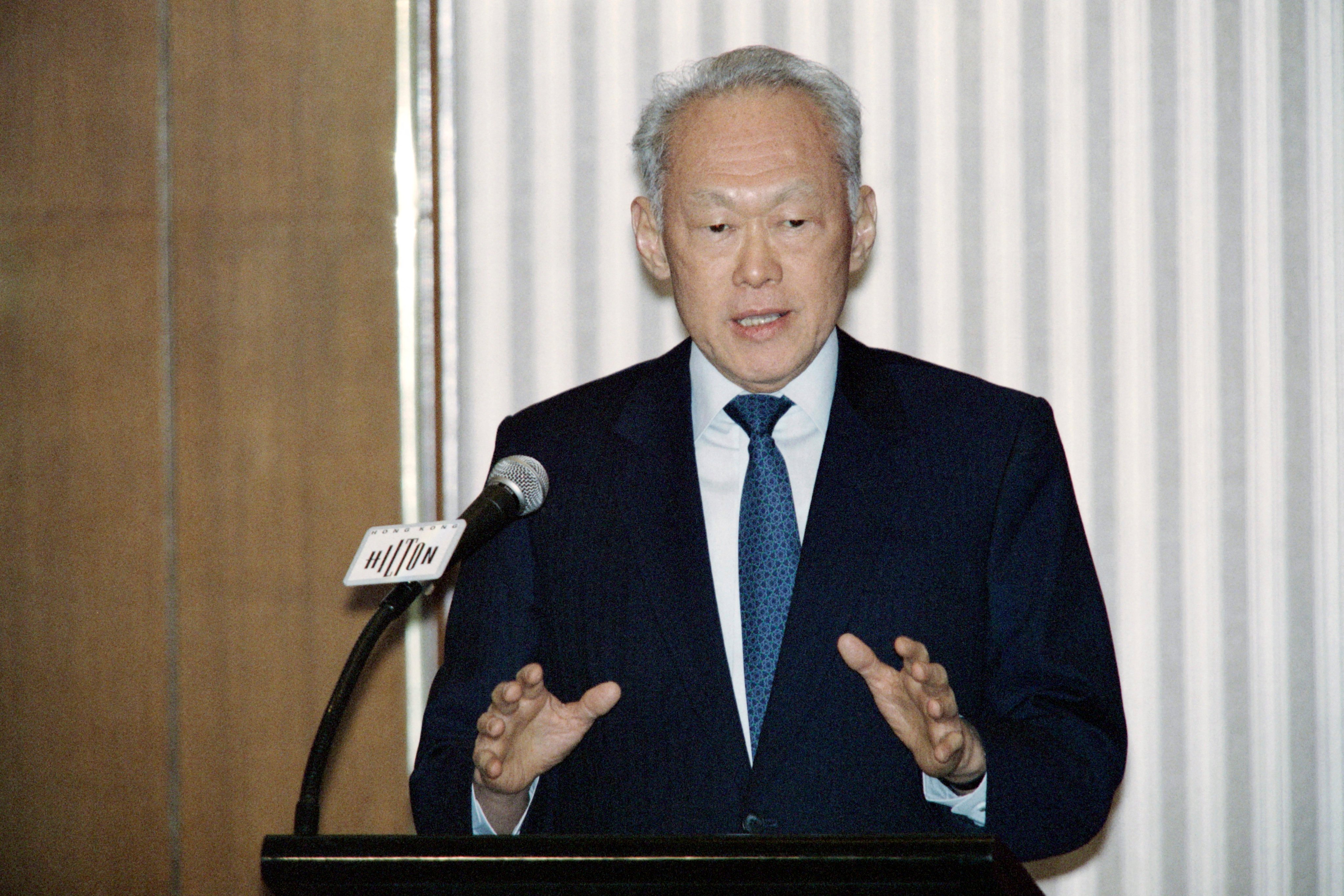

S.R. Nathan was in the delegation. Later, he told me this story: During Lee Kuan Yew’s (LKY) talks with the Chinese, his hosts gave him a book, India’s China War. It was written by Neville Maxwell, a journalist and Oxford academic.

The book was a pro-China version of the border war between India and China. LKY knew the Chinese purpose: It was trying to draw Singapore into its orbit.

According to S.R., LKY put the book aside, and responded, saying words to this effect: This is your version. There is another version of the war.

That left a deep impression on S.R. “I was so proud of what the PM did.” Singapore would not be drawn to take sides. It was also a demonstration of LKY’s commitment to multiracialism.

Three-quarters of Singaporeans are ethnic Chinese. Hence, Singapore is seen in some quarters in Indonesia and Malaysia as a subversive Third China.

If Singapore did not disabuse its neighbours of the notion that it was a Third China, regional peace would be threatened. Malaysia and Indonesia would be suspicious of Singapore’s motives. Singapore would be vulnerable to external pressures, from the east and west.

During the Mao era, Zhou Enlai, China’s PM, had stated China’s policy on its diaspora: Ethnic Chinese living outside China should be loyal to the country they lived in. So the “kinsmen” welcome the Singaporeans received was not expected.

Today, under Xi Jinping, China sees all ethnic Chinese as belonging to a large extended Chinese family.

When I mentioned this to a former colleague, Tammy Tam, the editor-in-chief of Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post newspaper, she gave me her interpretation of the policy: Overseas Chinese who have citizenship in the country they live in should be loyal to that country. Many others do not, those are the people Xi had in mind.

Tammy knew China far better than I. Even if hers was a correct reading of China’s policy, it is, of course, not so simple.

Hence, in 2021, Singapore passed a law to prevent foreign interference in domestic politics by identifying anyone of value to a foreign power as a politically significant person.

In 2024, a Hong Kong-born Singaporean businessman living in Singapore was the first to be so named. Under the law, he has to declare, every year, his foreign affiliation, any migration benefits, and any donation of $10,000 or more.

The man had been invited to China’s annual political meetings held in Beijing. There, he had openly declared, echoing Xi, that it was the duty of every ethnic Chinese to help China tell its story better.

This geopolitical risk is a permanent one. Back in 2005, it had prompted Lee Hsien Loong to summon editors to the Istana.

The PM was concerned about Lianhe Zaobao’s coverage of China. The Chinese morning newspaper had published a series of three articles with what he saw as a pro-China tilt. Worse, one of the pieces was written by a staff writer, one of about 20 recruited from China.

He could not allow such coverage to continue without undermining Singapore’s neutrality, a fundamental foreign policy of the country.

The 2005 meeting would be the last one I would attend at the Istana. I was to retire in a year’s time.

These meetings stood me in good stead. I had used geopolitics as a guide as early as 1974 when I was given my first editorship. It helped me decide what stories to pursue, how they should be played up and how they should be developed.

I am convinced journalists serve their readers better by taking a geopolitical approach.

LKY, by doing this, was able to join the dots and fashion the course Singapore should take.

He had a huge database, built from extensive travels, from engaging world leaders, and reading widely.

He had one major advantage. Global leaders sought him out. They found his insights valuable, especially his reading of China.

He tapped into the database to draw lessons for Singaporeans. With his storytelling skills, he could hold their attention for hours, as he did each year when he spoke at the National Day Rally.

He went one step further with editors: He sent them a stream of articles he had read and which he believed would benefit their journalists.

In the early days, those articles were from the British press. His central message was that state welfarism was ruining Britain.

As a result, he did not tolerate any sign that indicated The Straits Times (The ST) was leaning towards the British model.

I clearly remember one such occasion. It was a letter that The ST published from a reader who was finding it increasingly difficult to pay his medical bills. He wanted more state support for health care.

But what angered LKY more was a picture of a Singapore hospital that The ST had published together with the letter. He saw that as the paper deliberately amplifying the reader’s point.

The other country LKY used to educate Singaporeans was Sri Lanka. His point was that Singaporeans must be aware of politicians playing the race card to win votes.

Civil war in Sri Lanka was wreaking havoc. In 1948, the country was freed from British colonial rule. Immediately, it was engulfed in ethnic conflict. Sinhalese politicians fanned racial sentiments, won their elections handsomely but paid a very heavy price.

In November 2024, I went into what was once the bunker used by the intelligence headquarters of the Tamil Tigers in Jaffna. The war was long over and the place had been converted into an art gallery of a resort hotel, called Fox Jaffna.

A plaque at the entrance of the gallery told the story, but from the perspective of the victors, the Sinhalese.

“Ravaged mercilessly during Sri Lanka’s decades-long civil war, the Jaffna Peninsula fell under the control of terrorist leaders for several years. During this period, it is reported that the Fox-Jaffna property was used as the rebel intelligence headquarters …”

But the makeover could not completely hide the wounds of war felt by the locals. I asked a local journalist what local history textbooks are used nowadays in the schools. His reply, unhappiness evident in the tone: They are published in Sinhalese by the authorities in Colombo. Jaffna has a local Tamil version of history, but it is not used in schools.

Travelling with members of the Singapore Press Club on a tour of Sri Lanka, I saw the ruinous consequences of the civil war, not just in Jaffna but the whole country. It is distinctly Third World, except for the high-end tourist hotels, like the City of Dreams in Colombo.

When the country achieved its independence in 1948, it had been a model Commonwealth country, with public institutions that were superior to those in Singapore.

Then, as its PM Dr Harini Amarasuriya told the Singapore delegation, the paths of the two countries diverged.

LKY’s Sri Lankan lesson

The Sinhalese, who make up more than 80 per cent of the population, had resented British favouritism towards the nine per cent of Tamils. So, when they came into power, they unleashed severely discriminatory policies.

Sinhalese was made the official language, Buddhism became the official religion, and the country’s name, Ceylon, was changed to Sri Lanka. Tamils were forced to resign from their civil service jobs because they could not master Sinhalese.

University admission was based on ethnic quotas. Eighty per cent of places were reserved for the Sinhalese. Tamils were discouraged from joining the civil service.

The Tamils then launched a guerilla war that lasted from 1983 to 2009. Up to 100,000 lives were lost in the civil war.

LKY frequently spoke publicly about this tragedy.

Hence, Singapore’s strict policies like the ethnic integration policy to ensure public housing estates reflect the country’s multiracial balance. For affected Housing and Development Board owners, the pain is severe. The Malays and Indians found it harder to sell their flats, sometimes even if they offered them at lower prices.

For the nation, as a whole, the scheme has been worthwhile.

I left Sri Lanka after 10 days, with three vivid memories.

Dr Harini was impressive. She was clear-sighted about what her country needed to do, and she made no attempt to gloss over its fundamental problems. She deserves to succeed.

The Singaporeans also met a group of young Sri Lankans, who described themselves as “a tribe of smart, sassy and fun entrepreneurs” dedicated to making their country a leading Asian innovation hub. They exuded confidence, and I can see them making an impact.

Finally, the sense of pride in the voice of our local tour guide as he spoke of the world-class civil engineering works in building royal palaces many centuries ago, though they now lie in ruins.

Sam, the guide, has reason to be proud of his country as its history goes back more than 2,000 years.

Shortly after the Singapore group returned home, Sri Lanka voters made a historic decision. They gave Dr Harini’s party, led by a socialist-leaning president, a massive mandate in the parliamentary elections.

The people – a local political analyst, Krishantha Prasad Coorey, posted on LinkedIn – have turned their backs on racial politics, and had voted as Sri Lankans.

“Today marks the first time that Sri Lankans of all ethnicities across the country spoke with one voice, and placed their faith on a single leader. In one fell swoop, Sri Lanka made clear that it has had enough of race baiting, nepotism, class warfare, corruption, cronyism, political vendettas and rank incompetence.

“They saw in President Anura Kumara Dissanayake a leader they could trust, who sincerely cared for them, who would work hard for them, has no interest in political theatrics and amassing power for himself.

“Even before victory was declared, the President himself reminded Sri Lankans of the discipline and integrity required to not abuse a two-thirds majority to amass power, but to remain committed to strengthening democratic institutions.”

Sri Lankans deserve to see light at the end of the tunnel.

I have dwelt on two of LKY’s political assets – his geopolitical makeup and his huge database. There is a third, a legendary thirst for learning.

He never stopped learning. One of his closest friends told me that even in the final months of his life, he did not miss his daily Mandarin lessons.

He was 91 when he died on March 23, 2015.

Excerpted from Ink and Influence: An OB Markers Sequel by Cheong Yip Seng, published by World Scientific Publishing. Cheong also served as an editorial adviser to the South China Morning Post.