Why China’s leaders seek a culture that is both modern and distinctly Chinese

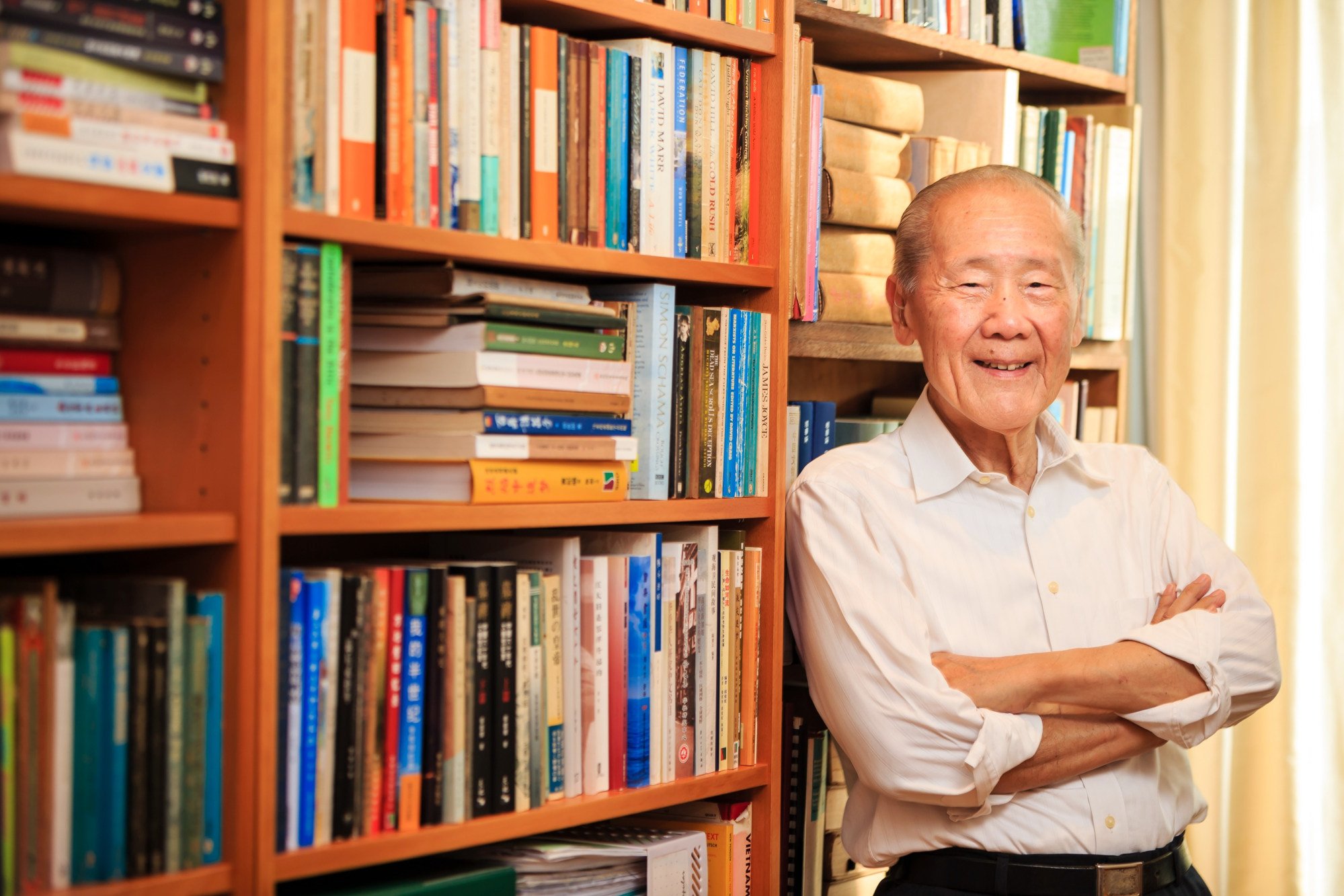

Historian Wang Gungwu on China’s quest for a unifying national ethos, fusing global insights with heritage to ensure stability in a changing world

Renowned historian Wang Gungwu’s Roads to Chinese Modernity: Civilisation and National Culture traces China’s transformation from an ancient civilisation into a modern nation-state shaped by revolution, reform and global engagement. Drawing on decades of scholarship and his unique perspective as an overseas Chinese intellectual, Wang reflects in this excerpt on Deng Xiaoping’s legacy and the enduring challenge facing China’s leaders today: how to build a modern national culture that embraces global ideas while remaining recognisably and distinctively Chinese.

The genius of Deng Xiaoping in 1978 was to see that China could not go down the road of revolution again. The word he used was “reform”. By this, he was asking the Communist Party to recognise that the revolution had been successful in 1949; the time had come to consolidate what had been achieved by learning from the lessons and mistakes of the past. When Deng called for “reform and opening up”, there was a national sigh of relief.

The idea of no more revolutions was something so welcomed by most people that it may be described as the secret of China’s success in the decades that followed. What is still unclear, however, is whether the new generation of leaders are free of the idea that Chinese culture is holistic.

When I talk about the quest for a new cultural identity, I am not certain whether the Chinese people have really moved away from the heritage of culture as a holistic unity. Why do I stress this? Because it is a new challenge to build a new culture that can stand by itself in the world today. Globalisation has made the world much smaller. New ideas are transmitted very rapidly. They include some of the most advanced ideas in science and technology, which all the Chinese admire and are willing to learn without any hesitation whatsoever. For many, this has demonstrated to them that globalisation has enabled the world to be one.

There is a global process going on and one day, some kind of global culture that all human beings could subscribe to and believe in might be created. I am not yet sure if that is part of the popular vision among the Chinese today. There are many signs which suggest that the Chinese deeply hanker for the kind of civilisation they once had, of which they were so proud. I think that old cultural identity is truly gone.

But maybe some valuable parts of it could be recovered and given new life by incorporating new ideas that are coming from elsewhere. With new mixtures or compositions, China could build something that will be distinctively, if not uniquely, Chinese.

As I described earlier, what the Chinese people focused on for the past century were the differences between two roads to progress. One required them to reject their past and totally accept new ideas from the West, whether they came from the capitalists or the communists, to replace what was obviously obsolete. This was still a holistic approach that demanded total acceptance of something new to remake China. Mao Zedong might not say that he subscribed to such a view, but the extreme ends he sought for his Cultural Revolution would suggest that totality.

Others were less ambitious and chose to avoid such a lofty vision. They were more modest in what they hoped for, to preserve what they could of what was good, universal and valid from the past traditions, while at the same time learning from outside, from the West in particular, science, technology, the values of modern society, modern politics and modern economics. Draw them all in and use them to enrich whatever was there that was worth preserving: a very moderate position, a position of compromise and willingness to reshape, readjust and readapt to save what they wanted from the past that was there.

There were many schools in between, but these were the two choices that the various leaders of the Nationalist Party and the Communist Party put before the Chinese people. When the People’s Liberation Army won on the battlefield, the people prepared to live with the Communist Party’s choice. They only began to rethink and start afresh 30 years later, when Mao Zedong led the country to great disasters.

Of course, it was never quite afresh because Deng Xiaoping never intended to throw out the baby with the bathwater. He reaffirmed faith in the Communist Party as the foundation of modern China and set out to reform it to make it stronger and something that could be long-lasting. Deng was a revolutionary who had fought with Mao Zedong and had seen many of his comrades sacrifice their lives for their ideals. What he wanted most was to preserve and improve what the revolution had achieved in 1949.

It was in that context that his reforms depended on the Communist Party structure of power; only that could ensure the country’s continued stability and bring about the rapid economic development that was desperately needed. Deng believed that the goals of socialism should replace those established by the Confucians and Legalists, but expected its progressive ideas to have Chinese characteristics.

This feature has been a source of merriment among his critics, but he was serious that parts of Chinese traditional culture were essential for a future national culture – a cultural identity that could still be recognisably Chinese and not a pale imitation of somebody else’s. In that way, Deng was not so different from those Chinese intellectuals who still hankered for the time when Chinese civilisation was unique.

Implications for the future

The quest for a new culture is far from ended. It is ongoing among the political leaders as well as the intellectual elites in China, who write about this all the time. I cannot imagine them not thinking about the future of China in that context. It was not enough for the country to be wealthy and strong. It was more important to be united and stable politically, economically and socially, with a sense of the oneness of China. Without that, there would not be a modern China. All the new ideas and methodologies would not have had the soil to build on, and the new one might end up becoming nothing more than an imitation of other people’s values and institutions.

That would not satisfy the vast majority of the intellectual Chinese whom I know. To them, they are willing to wait however long it takes, and to use whatever means necessary to enable that to grow. The ultimate goal is to have something that could proudly be called Chinese.

Can they do that? Can they really build a new and distinctively Chinese culture in the midst of rapid globalisation in the world? I am not sure. But I think one should not underestimate the willingness of the Chinese leadership in all fields to want to try. They will try to give substance to what Deng Xiaoping meant by having Chinese characteristics. They are not sure how much of the old traditions can still be fished out and given new life, and how to merge them with the new ideas that are reaching them from all over the world. I doubt they have a timetable for this, but that is no reason for worry. The Chinese people seem content to have that as their ultimate goal.

What will be the final product of all this frenetic activity that has made such a difference to China in 30 years?

In the meantime, what is likely is that they would still want to affirm that there is something Chinese today in China. This is not necessarily dependent on the traditions of old China, although they will not deny that there is much greatness and richness in the old Chinese culture that they can be proud of and that they could bring back into service again. But they are open to new ideas, to accept all the methodologies, technologies and institutions that they think could fit in to make China’s new culture possible. I believe that they have the openness of mind to do that.

But they do know that in their present stage of development, their government feels insecure because the process of change is so rapid. If the rest of the world can feel the drama of growth in China, can you imagine how the Chinese people feel about the speed of that growth around them? It is transforming their lives and the conditions under which they live, producing wealth where none had been, heightening inequalities where there had been equality, producing equalities where there had been centuries of inequality, all these happening almost simultaneously and at all levels. It has been bewildering to most Chinese to come to terms with and understand what all this can add up to. What do they really mean, how will they ultimately resolve itself, what will be the final product of all this frenetic activity that has made such a difference to China in 30 years?

I do not think anybody in China or elsewhere knows, but I think you can take it that there are Chinese people now deeply involved in trying to work out how this will end. Not end in the sense of something that is final and finished, but end in something that is recognisably Chinese that they could say comprises the best of what is Chinese with the best of what the rest of the world can offer. Above all, this product is something that clearly benefits the Chinese people.

Excerpted from Roads to Chinese Modernity: Civilisation and National Culture by Wang Gungwu, published by World Scientific Publishing.