Why China-Russia ‘troika’ talks are back on India’s table

New Delhi’s cautious openness to reviving the long-dormant Russia-India-China dialogue signals a careful hedging of its geopolitical bets

As friction with the West builds over energy imports and trade, India is weighing a delicate recalibration: reviving its long-dormant trilateral dialogue with Russia and China, even as it insists it remains committed to its partnerships with the US and its allies.

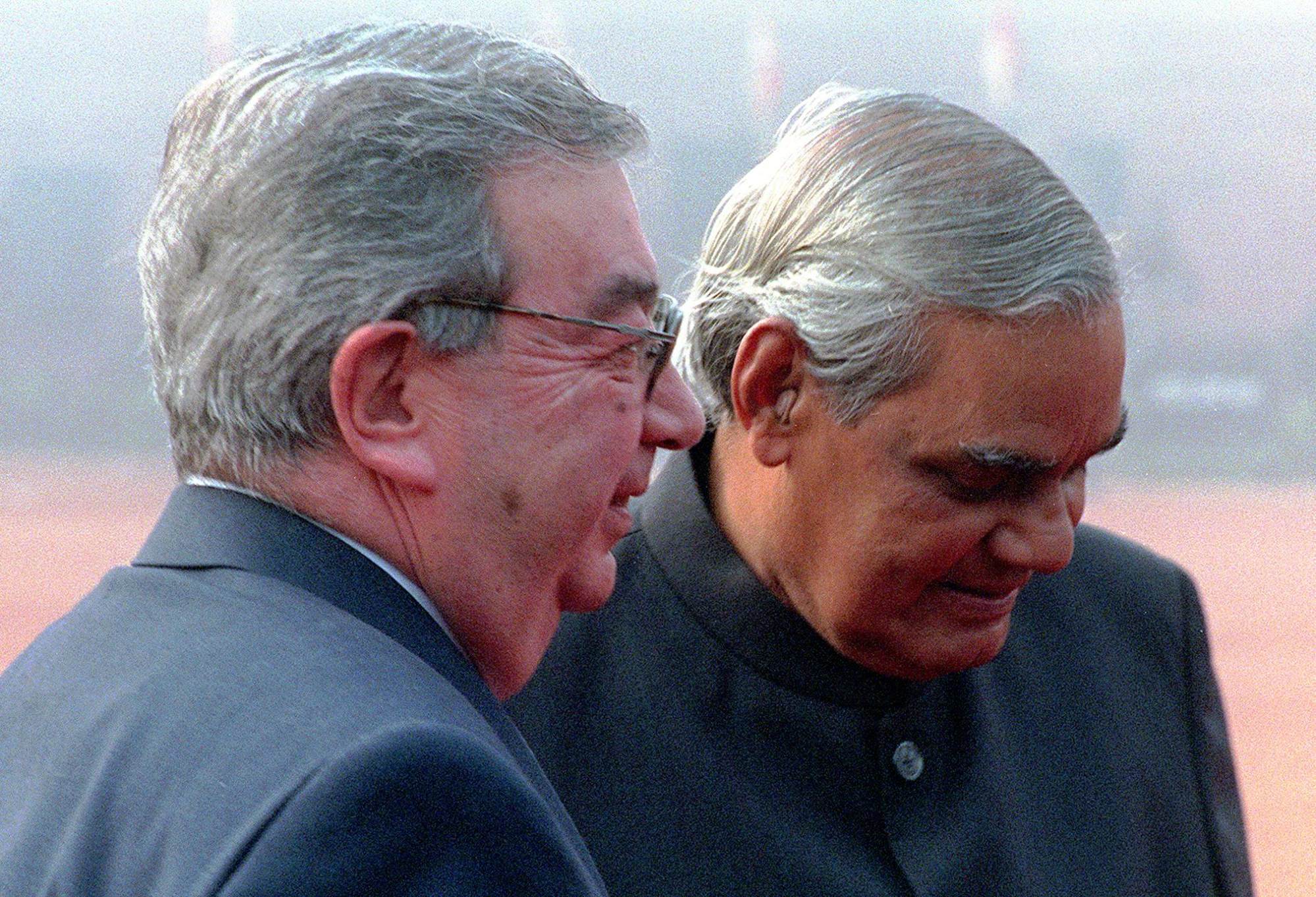

India indicated earlier this month its openness to resuming the Russia-India-China (RIC) dialogue, a platform established in the early 2000s to foster coordination among the three Eurasian powers.

Describing the RIC as a consultative mechanism for addressing shared regional and global challenges, New Delhi’s Ministry of External Affairs emphasised on July 17 that any decision on resuming talks would be taken “in a mutually convenient manner”. No timeline was provided for when this might happen.

The move came just weeks after Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov had voiced strong support for reviving the format. Speaking at a conference last month, Lavrov reaffirmed Moscow’s desire to “confirm our genuine interest in the earliest resumption of the work within the format of the troika – Russia, India, China – which was established many years ago on the initiative of former Russian prime minister Yevgeny Primakov”.

Analysts suggest the impetus behind India’s overture stems from growing frustration with what it perceives as Western “double standards”. Sriparna Pathak, a professor of China studies and international relations at O.P. Jindal Global University in India, pointed to recent warnings from Nato chief Mark Rutte that India could face “100 per cent secondary sanctions” for buying Russian oil.

Pathak said India had consistently maintained that securing its energy needs was an “overriding priority” and had previously “called out the hypocrisy” of European nations who continue to import substantial amounts of Russian oil and gas.

EU member states bought €21.9 billion (US$25.72 billion) worth of Russian oil and gas in the third year of the Ukraine war – one-sixth more than the €18.7 billion allocated to Kyiv in financial aid in 2024, according to the Helsinki-based Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air think tank.

Another factor was the United States’ “transactionalism” under Donald Trump, Pathak said. The India-US bilateral trade deal was stalled due to “hypocrisy and constant and unnecessary threats of tariffs” from Washington, she said, particularly regarding access to India’s agricultural sector.

While China “is simply not a choice for India”, she argued that Russia was a viable partner, having “not engaged in hypocrisy in ways that the US has”.

“This is the biggest reason for the rumblings behind RIC,” Pathak said. “India chooses its own national interests and will not give in to bullying.”

Delhi’s China carrot

Although India is interested in reviving RIC, it is proceeding with caution to avoid the perception that it is aligning with Beijing and Moscow against Washington, according to Ivan Lidarev, a visiting research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Institute of South Asian Studies.

Delhi would prefer to “improve relations with China a bit more” before fully committing to the trilateral, potentially using RIC as a “carrot” in its ongoing thaw with Beijing, the security expert said.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

“RIC reassures Beijing that Delhi is not aligned with Washington,” Lidarev added.

Ties between India and China, strained since the deadly Galwan Valley clashes of June 2020, have shown signs of gradual normalisation in recent months. Last week, India announced the resumption of tourist visas for Chinese citizens for the first time in five years.

Lidarev said India’s consideration of RIC was also a hedge against growing instability and unpredictability in the global order, particularly amid concerns over an “unpredictable and aggressive” US administration.

“[RIC] allows India to hedge its political and economic bets on the international stage and gives India more engagement options beyond the West,” he said, describing the platform as a source of “leverage” against the US.

India’s calculations are also shaped by the possibility that Trump could impose tariffs on countries buying Russian oil, including India and China. Such a move could trigger a crisis in US-India relations, Lidarev warned.

“The tariffs are a serious threat to India’s economy and can potentially provoke a crisis in relations with the US, in case India resists them,” he said, adding that Delhi was “clearly preparing for this possibility”.

Recent setbacks in US-India relations, including Washington’s stance and rhetoric during the Indo-Pakistan conflict in May, as well as fraught trade negotiations – particularly over agriculture and non-tariff barriers – have deepened India’s doubts about the US.

“More broadly, India has begun to doubt US reliability and resent US demands, while Washington has become much more impatient with Delhi’s strategic autonomy and its market protectionism,” Lidarev said.

India was willing to pay a “substantial” price to keep ties with Washington cordial, he said, but “there are limits to how steep this price can be”.

Gaurav Kumar, a researcher at the United Service Institution of India, a defence and security think tank, noted that with India set to chair Brics next year, Delhi was keen to demonstrate its capacity to act as a “stabiliser” able to engage both the West and Russia.

China’s recent gestures, including reopening the Kailash-Mansarovar pilgrimage route for the first time since the pandemic and hosting regional forums, signalled a willingness to “reset the tone”, Kumar said.

“Reviving the RIC offers a stabilising platform that may ease tensions, not escalate them, by fostering dialogue among key regional players,” he said.

“Beijing’s recent steps have opened the door, now it is up to all three nations to walk through it.”