Warship diplomacy: UK carrier makes a splash in Singapore

HMS Prince of Wales’ decision to dock at Marina Bay aims to boost public outreach, showcase Britain’s influence as a global power, analysts say

The decision by a British carrier strike group to dock at a civilian cruise centre instead of a naval base in Singapore during a visit has put into focus London’s priority on soft power and public outreach in the region amid conflict in the Middle East.

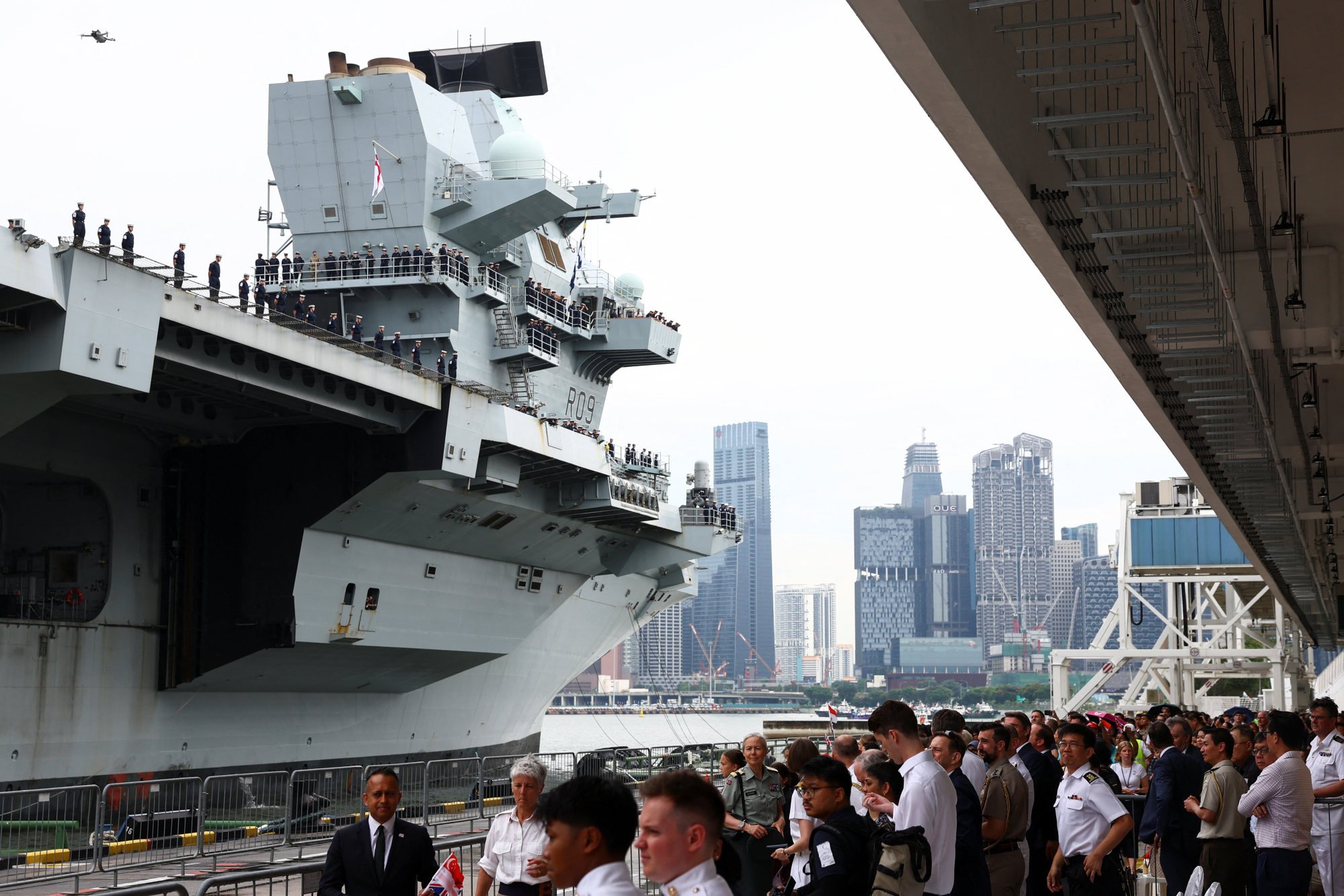

With the city state’s iconic skyline as a backdrop, the 284-metre-long, 80,000-tonne HMS Prince of Wales became the first warship to dock at the Marina Bay Cruise Centre on Monday for its first port of call as part of its eight-month deployment for Operation Highmast.

While experts told This Week in Asia that the main trade-off of not berthing at Changi Naval Base was the extensive security measures offered, the decision showed London’s desire for soft power projection.

“I believe the UK assesses the security risk is low, and London places higher priority on soft power projection and high publicity, and to create greater awareness of the UK’s defence contributions to Southeast Asia,” said Abdul Rahman Yaacob, a research fellow in the Southeast Asia Programme at the Lowy Institute.

He noted that sufficient security measures would be in place at the cruise centre, with Singapore’s defence ministry and authorities ensuring the security of the carrier while it is docked at Marina Bay Cruise Centre.

British High Commissioner to Singapore Nikesh Mehta explained during a media briefing last Thursday that the choice of the civilian centre was centred on visibility and accessibility, and to have “one of the world’s most advanced warships sitting against one of the most iconic skylines in the world”.

While docked in the city state for the week, the carrier will play host to a range of activities including public tours which saw more than 8,000 people ballot for some 600 spots, and invite-only events like an e-sports tournament and a defence and security expo with British companies in the carrier’s hangar.

Mehta rejected using the word “carnival” to describe the event line-up and stressed that the deployment of 4,000 personnel was a serious one, yet the public diplomacy aspect was also vital to showing the UK’s commitment to the Indo-Pacific.

“Having the carrier strike group here with a multinational group of other ships with it is an important signal of the importance of this region to UK security and growth, but if it’s tucked away at Changi, it’s quite hard for people to see that and understand it, and for them to see that the UK remains an important global defence power,” he said.

Mehta also pointed out that stability in the Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic was indivisible and much of the world’s trade went through this part of the world. “Ensuring that we’ve got stability for freedom of navigation and freedom of movement is absolutely essential, and that’s the main reason why our carrier strike group is coming,” he said, prior to the carrier’s arrival.

Some 4,000 UK personnel from the Royal Navy, the British Army and Royal Air Force are part of the deployment, with the carrier strike group engaging more than 30 countries and conducting exercises in the Mediterranean, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, Japan, South Korea and Australia.

The Royal Navy said in April that up to 24 F-35B fighter jets and 16 Merlin and Wildcat helicopters would fill out the bulk of the air wing for the carrier strike group during the deployment.

Next month, the carrier strike group will participate in the Australian-led multinational Exercise Talisman Sabre, which involves the United States and other regional partners. While in Australia, it will conduct a port visit to Darwin, to develop the Aukus relationship with Australia, the UK and the US, before making port calls in Japan and South Korea.

On its return journey, it will participate in Exercise Bersama Lima, marking the first time since 1997 that an aircraft carrier is taking part in the Five Power Defence Arrangements’ capstone exercise.

Muhammad Faizal Abdul Rahman, a research fellow at S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, noted that it was possible the UK perceived that the re-routing of US military assets, like the USS Nimitz aircraft carrier, to the Middle East could create gaps in Western force projection in the Indo-Pacific.

“Continuing with the UK’s deployment could help to some extent address this concern by substituting US carrier presence with a UK one. Furthermore, a US military distracted by the Middle East conflict, could create opportunities for UK and other European powers to promote their defence and economic influence in the Indo-Pacific,” Faizal said.

Collin Koh, a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, said the decision to berth the carrier at Marina Bay Cruise Centre instead of Changi, which would facilitate public visibility and greater public access to the slate of public outreach events, “appears to reflect London’s desire to promote its ‘Global Britain’ posture beyond mere ‘show of flag’ exercise of presence typically seen in the regional military engagements”.

Global Britain refers to the UK’s post-Brexit foreign policy and trade strategy to champion a rule-based international order and show that the country is open, outward-looking and independent on the world stage.

“London might have viewed the need to widen public outreach to not only promote this ‘Global Britain’ strategy but also to dispel any potential disinformation or misinformation regarding UK military presence in the Indo-Pacific,” Koh added.

Koh noted that misinformation included the narrative put forth by Chinese state-affiliated media outlet Global Times in 2021 that questioned the UK’s naval deployments in the region then.

The news outlet referred to the UK as a declined power seeking to revive its past glory, and questioned the effectiveness of London’s show of force in the region.

“Based on these, I’m not surprised if London dedicated efforts to public outreach to seek to dispel such narratives,” Koh said.

He argued that public outreach programmes were not mutually exclusive from the traditional defence or naval diplomacy activities the carrier would conduct.

“In today’s more complicated and complex geopolitical landscape, I believe public outreach has become ever more critical in the battle of strategic narratives. The geopolitical tensions we see happening in this region and beyond are in no small part also about contestation of the geopolitical narrative space, shaping public perceptions and how that impinge on policy.”