TikTok fuelling rise of fascist youth movement in the Philippines, experts warn

The far-right Philippine Falangist Front seeks to evoke nostalgia for Spanish rule while calling for Catholic authoritarianism

In a TikTok video viewed more than 170,000 times, the eyes of senatorial candidates from the Philippines’ ruling coalition are blacked out with a caption that reads: “Liberal politics is the most corrupt thing you can get.”

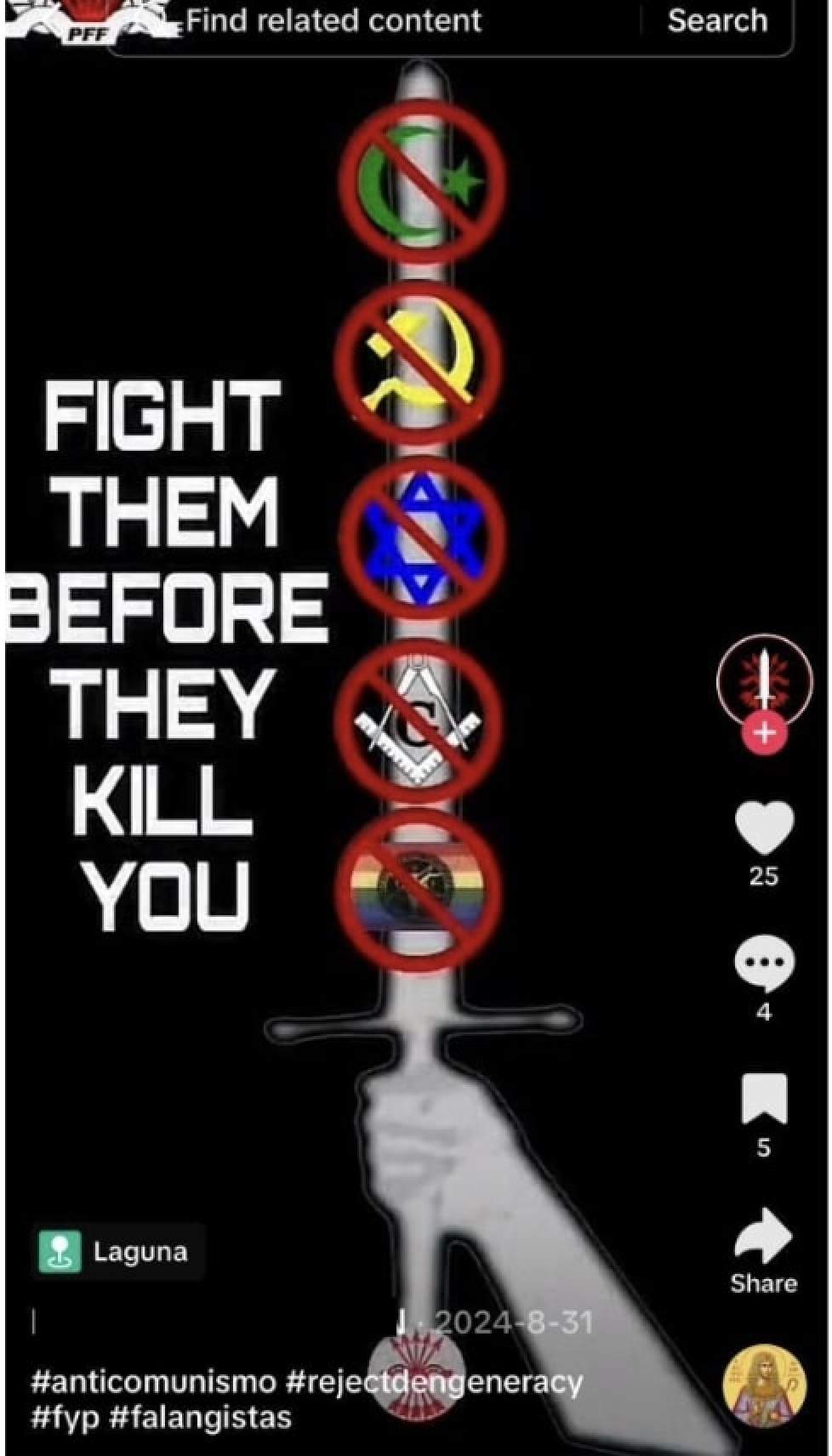

Another video, more ominous still, flashes the phrase “Fight them before they kill you” over symbols of Muslims, Jews, communists, Freemasons and the LGBTQ community – each struck through by a sword.

They are just a few examples of an increasingly visible fringe movement brewing in the Philippines’ online underworld, where a new generation of far-right extremists is using social media platforms such as TikTok and Discord to recruit, radicalise and rally disaffected youth.

The movement, known as the Philippine Falangist Front (PFF), is part of a small but growing network of digital communities promoting fascist ideology in Southeast Asia, according to a recent study by the Global Network on Extremism and Technology.

Their message is incendiary: the Philippines is a nation in crisis, and only a return to authoritarian Catholic rule can restore order.

“They commonly produce content or engage in discussions lamenting the Philippines’ and the world’s descent into a so-called godless society,” said Saddiq Basha, the report’s author and a research analyst at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

The perceived culprits, according to the PFF: communists, Muslims, LGBTQ individuals, Freemasons, Jews, and a modern society they describe as decadent and degenerate.

Nostalgia for fascism

The PFF draws ideological inspiration from falangism, a far-right doctrine founded in the 1930s in Spain by José Antonio Primo de Rivera. Characterised by nationalism, authoritarianism, Catholic identity and violent anti-communism, falangism gained traction during the regime of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco.

The Filipino variant reinterprets these tenets through the country’s colonial Catholic heritage, reframing the Spanish era as a golden age and positing Catholicism as the only legitimate moral authority. One of the group’s viral posts calls the Catholic Church “the one true Church founded by Christ Himself”.

According to Basha, the group appears to consist largely of young Filipino men, with a presence not only on TikTok but also on Facebook and encrypted platforms like Discord. While its total follower count appears to be in the low thousands, the group’s most active members maintain a steady stream of ideological content and offline organising.

“Based on the nature of their propaganda content and online discussions, there are indications of a small inner cadre of highly active members who appear more ideologically committed,” Basha said. “This group likely plays a central role in producing propaganda and coordinating offline activities.”

The PFF first surfaced as a reincarnation of an earlier self-described Christo-fascist group known as Christ Korps, which had promoted similar views on Discord before being deactivated for breaching the platform’s rules on violent extremism.

“They resurfaced with a new identity – recycling the same propaganda, messaging, and user-generated content,” Basha said.

Among their offline activities: burning magazines published by the Iglesia Ni Cristo, a politically influential church that claims 2.8 million members in the Philippines. Posters have also been vandalised with slogans decrying political dynasties and liberalism.

Fertile ground for radicalisation

Basha noted that a key component of the group’s propaganda was the constant portrayal of the Philippines as a “nation in crisis”, with members often citing the Philippines’ instability to justify their ideological alignment.

“Through such imagery, PFF propaganda taps into followers’ deep frustrations over the perceived failure of the Philippine state,” he said.

The group capitalises on poverty, corruption, and persistent threats such as Maoist insurgencies, Moro separatism, and Islamist extremism to fuel what Basha described as “a pervasive sense of national decline and insecurity”.

These conditions, he noted, can foster feelings of marginalisation and helplessness, pushing individuals to seek alternative ways to regain a sense of meaning and control over their lives.

“They’re often navigating emotional turbulence and identity formation during their teenage years,” Basha said. “At that stage, their ability to regulate emotions and impulses is still developing, making them more reactive and impressionable.”

Basha added that far-right extremist groups are typically well-positioned to fill their needs for belonging, purpose, and self-worth, and offer black-and-white answers to complex social or political issues.

“What makes them especially potent is the way they operate in tightly controlled echo chambers, where extreme views are constantly reinforced and rarely challenged. For young individuals feeling isolated or disillusioned, that kind of certainty and affirmation can be powerfully persuasive,” he said.

Preying on insecurities

Rosana Pinheiro-Machado, professor of global studies at the University of Dublin and director of the contemporary extremism research lab Deeplab, said these movements are no longer confined to Europe or North America.

The young male demographic is “the most common profile associated with far-right online extremism across the globe,” she said. “These vulnerabilities have historically been exploited by various actors – from drug trafficking networks to terrorist groups – and now by far-right movements.”

“What these groups offer is a narrative that soothes anxiety by identifying scapegoats – often those who are even more vulnerable – as the enemy,” she added.

In Southeast Asia and other parts of the Global South, these dynamics are compounded by precarious economic conditions and aspirational cultures.

In the Philippines, widespread livelihood and labour insecurity, “coupled with a highly aspirational entrepreneurial culture”, create fertile ground for both libertarian and authoritarian ideologies to take root, Pinheiro-Machado said.

The country’s embrace of strongman politics has also made it more receptive to such ideologies. Former president Rodrigo Duterte, elected in 2016, gained popularity for his brutal crackdown on crime and drugs, as well as his anti-liberal rhetoric – an appeal now carried forward by his daughter, Vice-President Sara Duterte-Carpio.

“In the case of the Philippines, as in other countries in the Global South, we are dealing with large segments of the population who have normalised authoritarianism, violence, and the concentration of political power within families,” Pinheiro-Machado said. “These are not political cultures where democracy and universalism are deeply embedded values.”

Memes and menace

Basha said the PFF and other far-right subcultures in Southeast Asia appear to be non-violent, but warned that “this does not preclude the possibility of escalation”.

“A similar trajectory has already been observed in the West, where multiple far-right extremist attackers were shaped by or deeply engaged with far-right meme subcultures,” he added.

“With elements of that same subculture now diffusing into Southeast Asia, groups like the PFF could, over time, contribute to the normalisation of extremist ideas. This does not mean violence is imminent – but it does point to the value of early monitoring and research,” he said.

Online platforms have become increasingly harmful for political purposes as they have become conduits for “clusterisation,” or the capacity of social media to form tightly-knit groups around specific subjects or identities, Pinheiro-Machado said.

She added that TikTok has “not only embraced but also amplified this model”.

“Today, it plays a central role in disseminating far-right ideologies to younger generations through a seemingly harmless format – fun, entertaining content based on jokes, choreographies, and short, punchy messages. These formats are highly effective at capturing attention continuously, yet they often lack broader context, leading to widespread mis- and disinformation,” she said.