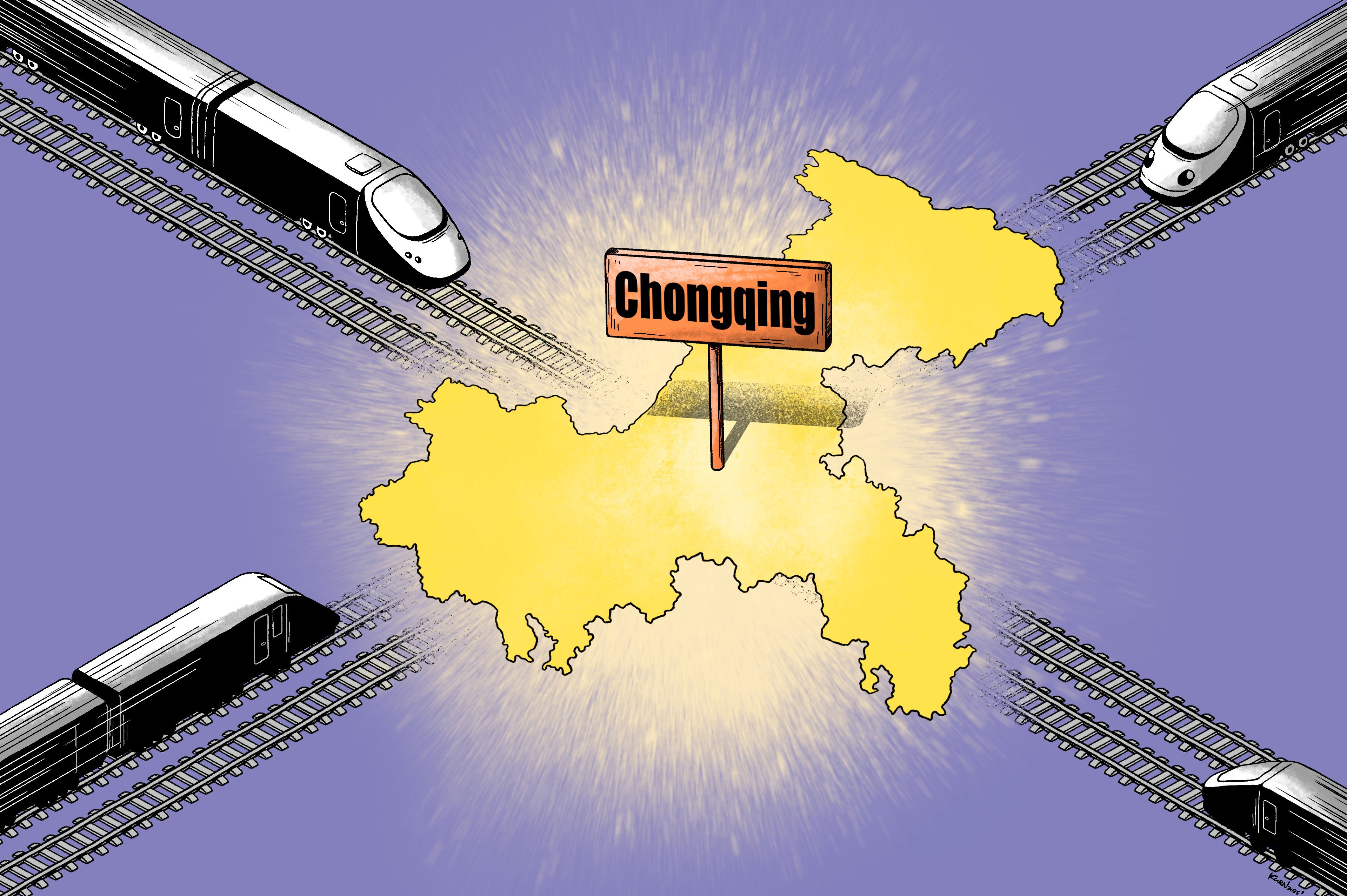

Suez Canal on rails? How this inland Chinese city wants to revolutionise global trade

The metropolis is already a rail-powered gateway to foreign markets – now, it wants to go one step further

In Tuanjie Village, in the heart of Chongqing – China’s largest inland city, best known for its spicy hotpot – orange gantry cranes hoist cargo onto goods trains bound for Europe and Russia. Each day, hundreds of containers pass through the sprawling 82,000-square-metre yard, exporting electric vehicles and components or returning with cars, meat, wine and dairy.

Just a five-minute drive away, blue cranes mark another yard – this one unloading tropical fruits and raw materials from Southeast Asia.

Over the past decade, the southwestern Chinese metropolis has evolved into a hub of international trade, thanks to the launch of two expansive cross-border rail networks. One runs west to Germany and the other extends south, reaching as far as Singapore – trade corridors that give China faster, more reliable access to global markets while offering other countries a clear route into its vast interior.

But the city’s ambitions go beyond simply doing business with foreign partners. It aspires to become a central node in the global economy through which other countries trade – a rail-based “Suez Canal”, connecting Asia and Europe.

The changes under way in Chongqing could offer a snapshot of how the world’s second-largest economy is deepening its global trade footprint amid rising geopolitical risks, including the possibility of a complete decoupling from the United States.

“Shipping goods from Asean to Europe via Chongqing by rail is 10 to 20 days faster than traditional sea transport,” said Liu Yizhen, vice general manager of the New Land-Sea Corridor Operation Company, which is in charge of the freight route from Chongqing to Southeast Asia.

The debut train on the fast track route, named the Asean Express, launched in October last year. It departed from Hanoi, Vietnam, and took five days to reach Chongqing, where its wagons were briefly reorganised before continuing for another two weeks to its final destination in Malaszewicze, Poland.

The service allows importers and exporters to streamline logistics by placing a single order to ship goods directly between Southeast Asian countries and Europe, according to Liu, whose company runs the route in collaboration with the China-Europe Railway Express operator.

“For clients prioritising speed and stability, land transport may be their preferred choice. Those seeking better prices might opt for maritime shipping,” Liu added.

The Asean Express now operates weekly freight trains. The route had already transported cargo totalling 1.65 billion yuan (US$229.6 million) by the end of April, Liu said.

Officials believe the groundbreaking initiative from Chongqing could revolutionise global trade, mirroring the city’s own experience as the birthplace of the China-Europe Railway Express, launched in 2011.

The idea of linking China and Europe by rail came from HP, the American computer and printer manufacturer. In 2009, the company proposed the route to local officials as a logistics solution that was faster than sea freight and cheaper than air.

Over the past 14 years, the route has expanded into a comprehensive rail network spanning China, Central Asia and Europe, bolstered through considerable government subsidies as a flagship project under the Belt and Road Initiative.

“Chongqing’s original conditions are far from ideal to develop an export-oriented economy,” said Huang Yiwu, deputy director and research fellow at the Chongqing Academy of Social Sciences, referring to its mountainous landscape and over 1,000 km distance from coastal ports.

“The China-Europe Railway Express has truly been a game changer.”

Chongqing’s industrial and manufacturing sectors have also thrived, as businesses ride the tide of the rail network to attract foreign orders. The city produced one-third of the world’s laptops, according to the city’s mayor in 2024. Among its flagship local brands are electric vehicle maker Seres Automobile – which produces EVs in collaboration with Chinese telecoms giant Huawei Technologies – and state-owned Changan Automobile.

Changan’s assembly plant for its EV line, Avatr, in western Chongqing, is capable of producing 50 cars per hour. Many of the vehicles are right-hand drive and ordered by markets such as Thailand, according to Tang Junze, a Changan engineer in charge of the final assembly of the vehicles. Once they leave the assembly line, the vehicles head directly to Tuanjie Village for export.

“In Chongqing, for every four cars exported, one is shipped internationally from Tuanjie Village,” said Han Chao, vice-president of Chongqing International Logistics HubPark Construction.

In return, local officials and operating companies hope the city’s manufacturing strength could make the Asean Express more appealing to foreign clients by increasing the value added of transit goods.

“It’s like connecting two markets through bonded zones and logistics channels,” Han said. “When a company [in Asean] wants to import second-hand computer numerical controls from Germany, it can have the machines upgraded and refurbished in [Chongqing’s] bonded zones before heading to Southeast Asia.”

This provides Asean countries with a more cost-effective alternative to directly purchasing brand-new equipment, while allowing EU countries to export more goods to global markets, Han said.

“As for China, we can leverage the advantages of these logistics channels to achieve a closed-loop business model by reducing factor costs and applying technological upgrades.”

The Asean Express is just one example of Beijing’s recent efforts to mitigate soaring external uncertainties amid economic tensions with the US. Beijing’s pivot to other markets – especially top trading partners like the EU and Asean – has become a priority since US President Donald Trump launched an unprecedented trade war in April.

Last year, Peru’s Chancay Port was also launched. Majority-owned by the Chinese state-owned enterprise COSCO, it became the first deep water port on South America’s Pacific coast, providing direct shipping to China in 23 days.

In May, at a new forum bringing together leaders from China, Asean and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) – comprising six Arab states bordering the Persian Gulf – officials signed a joint statement vowing to boost “seamless connectivity”, from developing logistics corridors to digital platforms.

This signalled China’s intention to support more infrastructure projects to connect these regions, according to Su Yue, principal economist for China at the Economist Intelligence Unit.

However, despite the vision, the path forward has rarely been easy – the China-Europe Railway Express’s track record being a case in point.

The service’s main routes currently pass through Russian territory. When the war in Ukraine broke out in 2022, many European traders – out of fear of sanctions or being perceived as friendly to Russia – returned to ocean shipping. The rail route only began to regain customers after the attacks by Yemen’s Houthi group on vessels passing through the Red Sea, starting in late 2023.

Since late last year, not long after the official launch of the Asean Express, a wave of goods seizures by Russian authorities also caused havoc on the China-Europe rail link, discouraging many traders and freight companies from using the service.

In October, Moscow banned certain goods from transiting through Russia, targeting dual-use items – such as mechanical and electronic products – that could be used on the battlefield in Ukraine. Many freight companies only became aware of the rule changes weeks later – after Russian authorities had already impounded large amounts of their cargo.

From January to April, the volume of westbound cargo on the China-Europe Railway Express dropped by 22.1 per cent compared to the same period last year, according to official data.

“Recently there has been some recovery in the freight traffic,” said Hu Ting, an employee at the departure station in Chongqing, in May. “But the ongoing war and sanctions are still bound to have a certain impact.”

China has intensified its efforts to develop an alternative hybrid sea-and-rail route, known as the Middle Corridor, which bypasses Russia by shipping goods across the Caspian Sea.

At the China-Central Asia Summit in June, Kazakhstan President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev also proposed building a joint cargo terminal at Kuryk port on the Caspian, according to local media reports.

Currently, the link faces a host of operational challenges, including strong winds on the waterway, logistical hurdles and excessive customs checks that increase costs and transit times.

With government subsidies now reduced or withdrawn entirely, achieving and sustaining profitability has also become a central focus for intercontinental goods train operators.

Lower operational efficiency in other countries along the route accounts for the lion’s share of the total costs, Han said.

“Whether our goods train services can turn a profit largely depends on overseas suppliers keeping their prices competitive.”

Despite the challenges, Han said he was confident the Middle Corridor would become a highly beneficial supplementary route connecting China and the EU.

“Any new endeavour undergoes a growth process. The old northern corridor, too, has taken over a decade of development to reach its current scale.”