South Korea, Japan step up as US targets China’s shipbuilding – can they succeed?

Washington’s curbs on Chinese shipping give Tokyo and Seoul a chance to revive their sectors – but analysts warn challenges remain

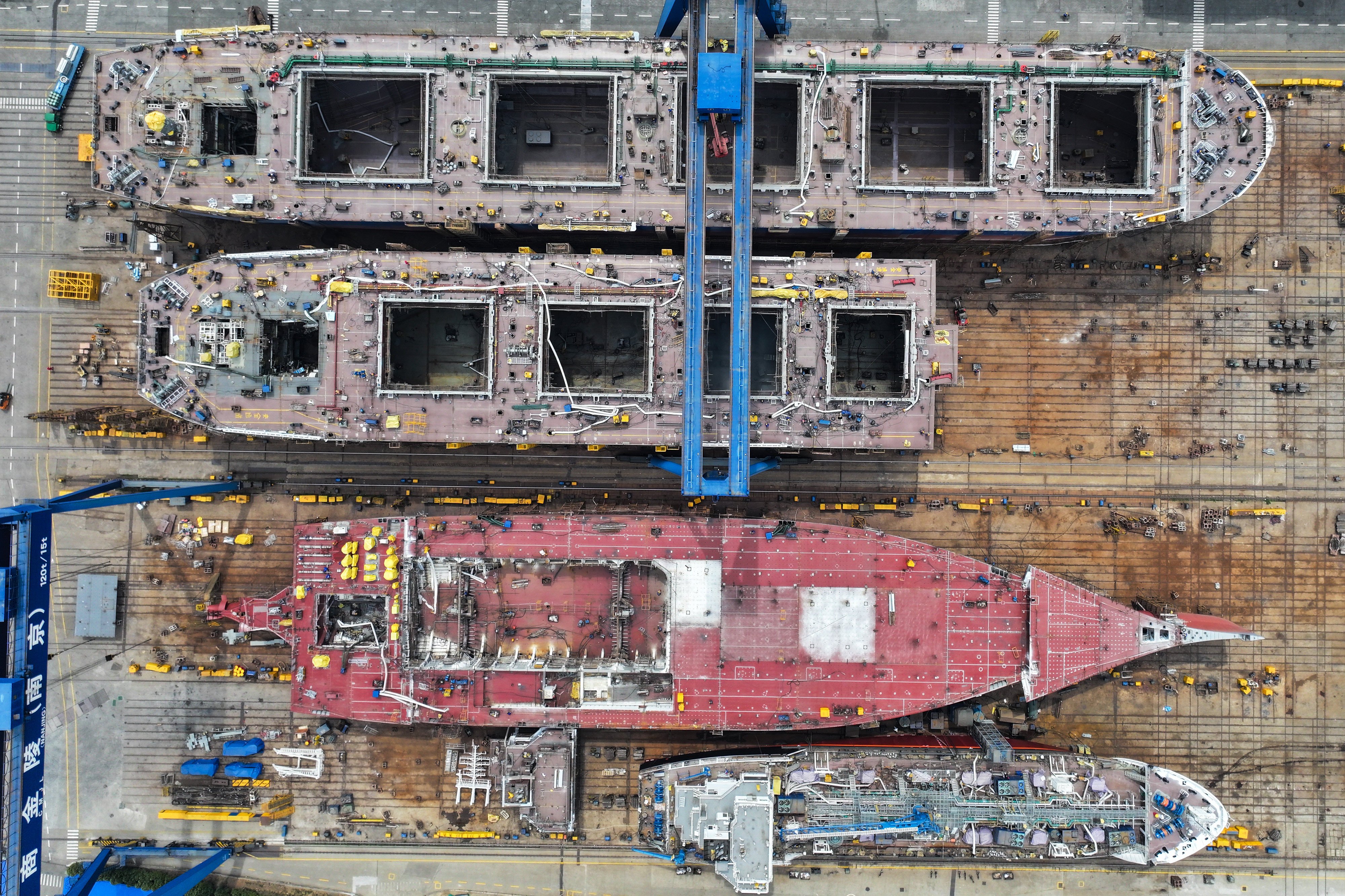

As the United States vows to curb China’s dominance in shipbuilding – despite its domestic capacity being nearly nonexistent – South Korea and Japan are looking to benefit from the rivalry and reclaim their competitive edge.

South Korea’s president, Lee Jae-myung, who took office a month ago, campaigned on supporting the industry – which he described as being “in major crisis”.

“Shipbuilding has been a core industry driving Korea’s exports and creating jobs,” he said in a social media post on May 14. “I will create a maritime power that leads the world beyond being a shipbuilding powerhouse.”

Although the new administration has yet to pass any specific policies or bills in support of the sector, it has outlined measures in the “New Government Growth Policy Guide,” said Eon Hwang, a Seoul-based shipbuilding analyst at Nomura.

The guidelines focus on vessel development, production improvements and new growth plans, according to a translation provided by Hwang.

The new administration also aims to promote the development of future vessels, such as autonomous and eco-friendly ships, through digitalisation, automation and improved personnel training and working conditions, the document said.

Jayendu Krishna, a director at Drewry Maritime Services, said that while automation and the green transition were ongoing trends, significant efforts would be required before these technologies reach maturity.

“South Korea has very aptly decided to focus on these [areas],” he said.

The new measures build on the previous administration’s efforts to position South Korea as a key shipbuilding partner to the United States – in both commercial vessels and naval ships – at a time when Washington has explicitly called for allied support in the sector.

Unhandled type: noscript {“type”:”noscript”,”children”:[{“type”:”text”,”data”:” “}]}

“}]}

Seoul has called for building special-purpose ships, such as naval vessels, and developing the ship Maintenance, Repair and Overhaul (MRO) market as a new source of growth.

Despite trade tensions with the Trump administration, cooperation between South Korea and the US, especially in the shipbuilding industry, is strengthening as Washington intensifies its regulations on China, South Korea’s President Lee said in March.

In April, Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI), a major South Korean shipbuilder, signed a memorandum of understanding with Huntington Ingalls Industries, the largest military shipbuilder in the US, to accelerate cooperation and technology sharing.

Another top domestic shipbuilder, Hanwha Ocean – which acquired Philadelphia-based Philly Shipyard in December – announced last month that it had received US approval to acquire a full stake in Austal, an Australian-based shipbuilder that holds major contracts with the US Navy, if it chooses to proceed with the deal.

Both HHI and Hanwha have had access to the US Navy’s MRO services since last year.

Even though most major shipbuilding docks are fully booked through 2027 and 2028, Hwang said no dormant shipyards have reopened in South Korea –despite promising demand from the US.

Expanded capacity would depend on whether the US continues to strengthen regulations on Chinese shipyards and whether the “Ensuring Naval Readiness Act” – which allows allies to build US naval vessels outside the country – gets passed, he said.

In the past two years, Chinese shipbuilders have secured about 70 per cent of new vessel orders globally, while South Korea’s market share has fallen to an eight-year low, according to the China Institute of Marine Technology and Economy, a research institute affiliated with China State Shipbuilding Corp.

The gap has put Korean shipbuilders under pressure, it said in a note on Wednesday.

“Now, the policy measures have been put in place, but their effectiveness will depend on their implementation and the domestic and external conditions,” it added.

Japan, the world’s third-largest shipbuilder, is also keen to benefit from US demand, which the Nikkei newspaper described as the “last chance” for the country’s shipbuilding industry.

Krishna agreed and said, “For the Japanese, it may be tantamount to a drowning man clutching at a straw if US shipbuilding receives a necessary push by Mr Trump’s administration.”

Tokyo is drafting a multibillion-dollar plan that would involve restoring or building shipyards before handing them over to the private sector for operation. The estimated investment could total nearly US$7 billion.

Last week, Japan’s largest shipbuilder, Imabari Shipbuilding, announced that it would acquire a controlling stake in the country’s second largest, Japan Marine United (JMU), turning it into a subsidiary.

“Imabari Shipbuilding and JMU will leverage each other’s strengths to compete with China and Korea, and will also make efforts to develop the Japanese shipbuilding industry by making quicker and more comprehensive judgments in terms of management,” Imabari said in a press release.

However, challenges remain. Japan has struggled to compete in the shipbuilding industry for some time, as it faces a decline in its labour force of about 30 per cent, Krishna said, noting that high production costs pose another significant obstacle.

“Consolidation may be a last-ditch effort to revive its shipbuilding industry,” he said.