South China Sea: Vietnam protests against Sandy Cay moves, raising flashpoint fears

Vietnam has urged China and the Philippines to ‘refrain from actions’ and respect its sovereignty over the archipelago

Vietnam’s protest over a reef in the South China Sea also claimed by the Philippines and China could become a “new flashpoint” in the longer term, analysts said, adding that Beijing might try to exploit differences between Manila and Hanoi.

Hanoi said on Saturday that it had sent diplomatic notes to China and the Philippines to protest against their activities in the contested South China Sea, urging them to respect Vietnam’s territorial claims.

Its foreign ministry spokeswoman Pham Thu Hang said Vietnam demanded that “relevant parties” respect its sovereignty over the archipelago, urging them to “refrain from actions that further complicate the situation”.

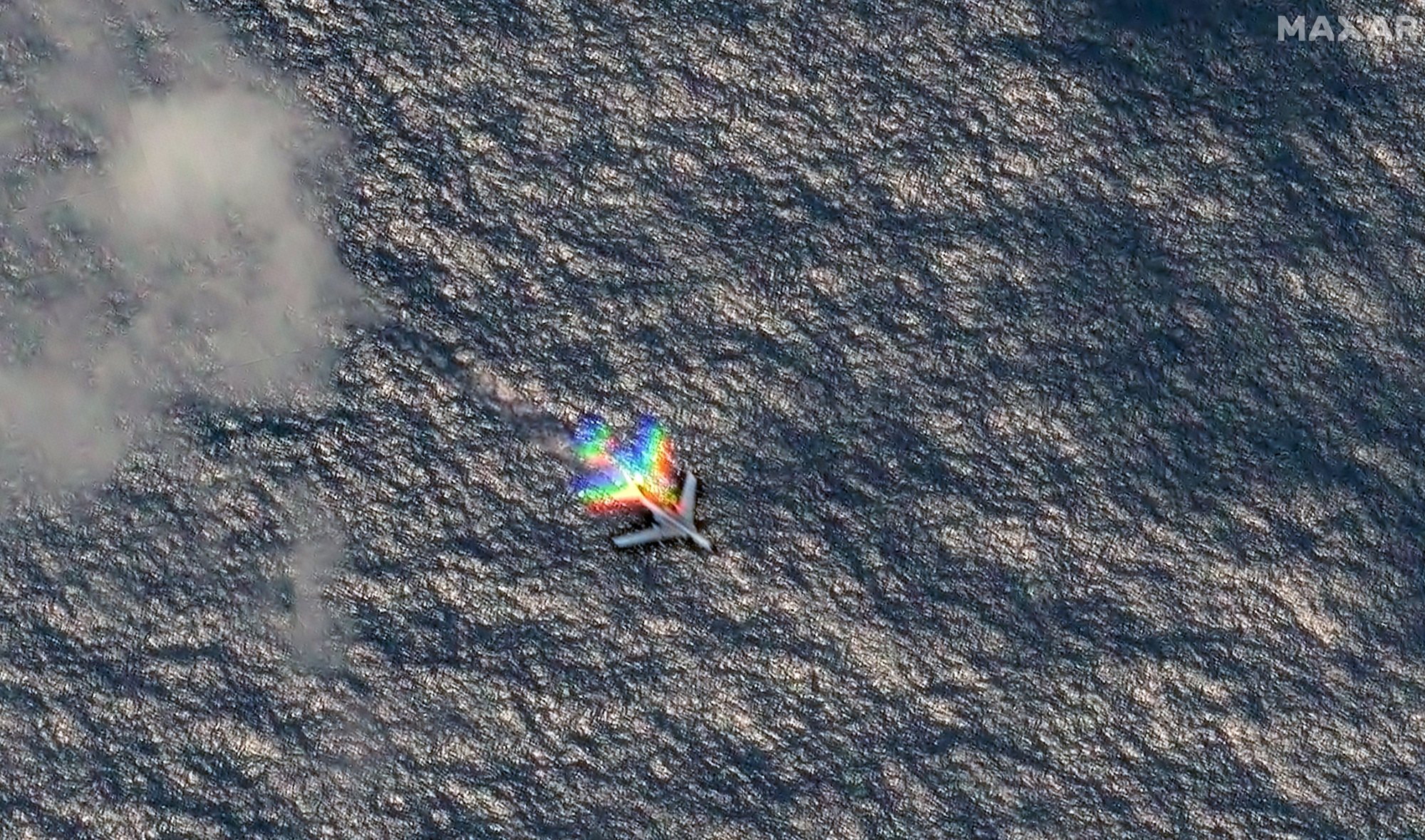

Chinese state broadcaster CCTV reported on April 26 that China’s coastguard had landed at Sandy Cay as part of a maritime operation to assert Beijing’s sovereignty over the Spratly Islands.

A day later, the Philippines sent its own coastguards and found no one there, with both nations raising their flags on the disputed reef.

Abdul Rahman Yaacob, a research fellow at the Lowy Institute’s Southeast Asia programme, said Sandy Cay was “potentially a new flashpoint” if the three countries decided to set up a more permanent presence by erecting facilities or deploying troops there.

“[Currently] it is less likely to be a new flashpoint in the immediate and medium term,” he said, adding that it was possible that all three were staking their claims but avoiding taking steps which might escalate tensions.

The Philippines and Vietnam have been working closely to manage their overlapping claims in the South China Sea and increase mutual trust.

In August last year, both countries agreed to advance defence and military relations and deepen collaboration on maritime security.

Rahman said that Beijing had often exploited differences among Southeast Asian claimants in the South China Sea, especially during code of conduct negotiations.

“China uses the ‘divide and conquer’ method during the negotiations, which could lead to misunderstanding among the claimants,” he said, noting that Beijing was more keen to deal with countries bilaterally rather than multilaterally.

Despite two decades of inconclusive discussions, China and Southeast Asian nations are “politically committed” to establishing legally binding rules for their conduct in the South China Sea by next year, according to a statement from Manila last month.

Lucio Blanco Pitlo III, a research fellow at the Manila-based Asia-Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation think tank, said new claims on natural features in the disputed waters “are bound to become new flashpoints in the South China Sea”.

“Denying occupation or control of such features by rivals becomes second nature, triggering a new round of contest in the dangerous grounds,” Pitlo said.

“Hanoi expressed its position to avoid the impression of acquiescing to the claims or actions of other disputants.”

Adding that Vietnam occupied the most number of features in the Spratlys, Pitlo said that Hanoi was also expanding and building new structures in the region.

Sandy Cay’s ‘higher value’

Pitlo said that Manila and Beijing were expected to attach “higher value” to Sandy Cay, which is near the Philippine-occupied Thitu Island and Chinese-occupied Subi Reef.

Thitu is the Philippines’ largest administered military outpost in the Spratlys group and Manila “is wary of possible Chinese designs” on the low-lying island, he added.

Describing the recent developments as concerning, Minh Phuong Vu, a PhD candidate in international relations at the Australian National University said that while raising a flag was “provocative”, it was also a “symbolic act with no legal weight under international law”.

Disputes over Sandy Cay were not new, she said, pointing to Manila’s proposal to build a fisherman shelter there in 2017, which was blocked by China.

Given the reef’s proximity to Thitu, there was potential for escalation “especially if China seeks to provoke Manila”, Vu said, noting that while Vietnam’s diplomatic protest might seem like an escalation, it was more likely a “routine assertion of sovereignty” over the Spratlys.

While Hanoi criticised Manila and Beijing for undermining both the declaration of conduct and code of conduct negotiations, Vietnam has not raised its own flag on any of the disputed islands.

“[This] suggests that it does not wish to further inflame tensions,” Vu said, pointing to the clear divergence in how the two Southeast Asian countries had responded.

“The Philippines appears to be engaging in a tit-for-tat with China, while Vietnam maintains a more restrained posture that emphasises Asean centrality and stability,” she said, referring to the Association for Southeast Asian Nations.

“Hanoi’s note can also be read as a subtle attempt to encourage Manila to refrain from actions that could further destabilise the area.”

While the Philippines has engaged in skirmishes with Chinese vessels in the disputed waters in recent months, Vietnam has maintained a much lower profile.

In April, Vietnamese coastguards conducted a joint patrol with their Chinese counterpart in the Gulf of Tonkin, described by Beijing as “a model for maritime law enforcement cooperation in the South China Sea”.

And although China hopes to exploit differences among Southeast Asian claimants, both Vietnam and the Philippines remain wary of Beijing’s intentions.

“While these divisions may impact Asean unity and bargaining power, it is not guaranteed that China can fully capitalise on them,” Vu said.

Additional reporting by Reuters