‘Shrimp among whales’: South Korea faces stark choices amid US-China rivalry

South Korea is coming under intense US pressure to pick a side, even as its new president would prefer to equivocate

The Korean peninsula has once again become a fulcrum of global anxiety, as South Korea grapples with intensifying pressure from its US ally to take sides in Washington’s deepening rivalry with China, all while North Korea rattles its sabres on Seoul’s doorstep.

Analysts warn that Seoul must tread this delicate geopolitical tightrope with unequalled agility to avoid being drawn into a major-power confrontation.

“As tensions escalate between superpowers, South Korea must retain strategic flexibility – otherwise, it risks becoming the proverbial shrimp crushed between two fighting whales,” said Chang Yong-seok, a senior researcher at Seoul National University’s Institute for Peace and Unification Studies.

Chang, who is also a former presidential adviser on national security, argues that Beijing must also play a constructive role if it seeks to ease US pressure on South Korea.

“To create more diplomatic room to manoeuvre for Seoul, China should take visible steps to stabilise the Korean peninsula, including restraining North Korea’s provocations,” he told This Week in Asia.

But the room for manoeuvre is shrinking. Koh Yu-hwan, emeritus professor of North Korean studies at Dongguk University, described South Korea as being mired in a policy dilemma, particularly regarding any potential conflict in the Taiwan Strait.

“Washington is urging Seoul to take clearer positions, but South Korea’s strategic interests are not always aligned with a full containment approach towards China,” Koh said. “This leaves Seoul with limited room to define its own stance in a fast-evolving security environment.”

A ‘linchpin’ of security?

When asked by This Week in Asia about Washington’s ties with Seoul, a US State Department spokeswoman said that the alliance was viewed as the “linchpin of peace, security, and prosperity” in Northeast Asia and the wider region and had been since 1953.

She emphasised in her email that this partnership, strengthened and modernised over seven decades, “must continue to adapt to a changing regional security environment” and highlighted the ongoing discussions that were being held on Seoul shouldering more of the defence burden.

Should conflict erupt on the Korean peninsula, China could pose a “third-party intervention threat”, according to Sydney A. Seiler, a senior adviser at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies’ Korea Chair.

Mainland Chinese forces would likely support Pyongyang, he said, making it “most prudent to plan today for how the US and ROK [South Korea] can prepare to deal with a breakout of hostilities” over Taiwan. Seiler added that Pyongyang’s stance amid such a crisis would be a critical variable.

“Most important is that Beijing and Pyongyang understand the shared US-ROK commitment” to counter aggression from China or North Korea, Seiler said. “Indifference, apathy, equi-distancing, or hedging risk would be exploited by Beijing.”

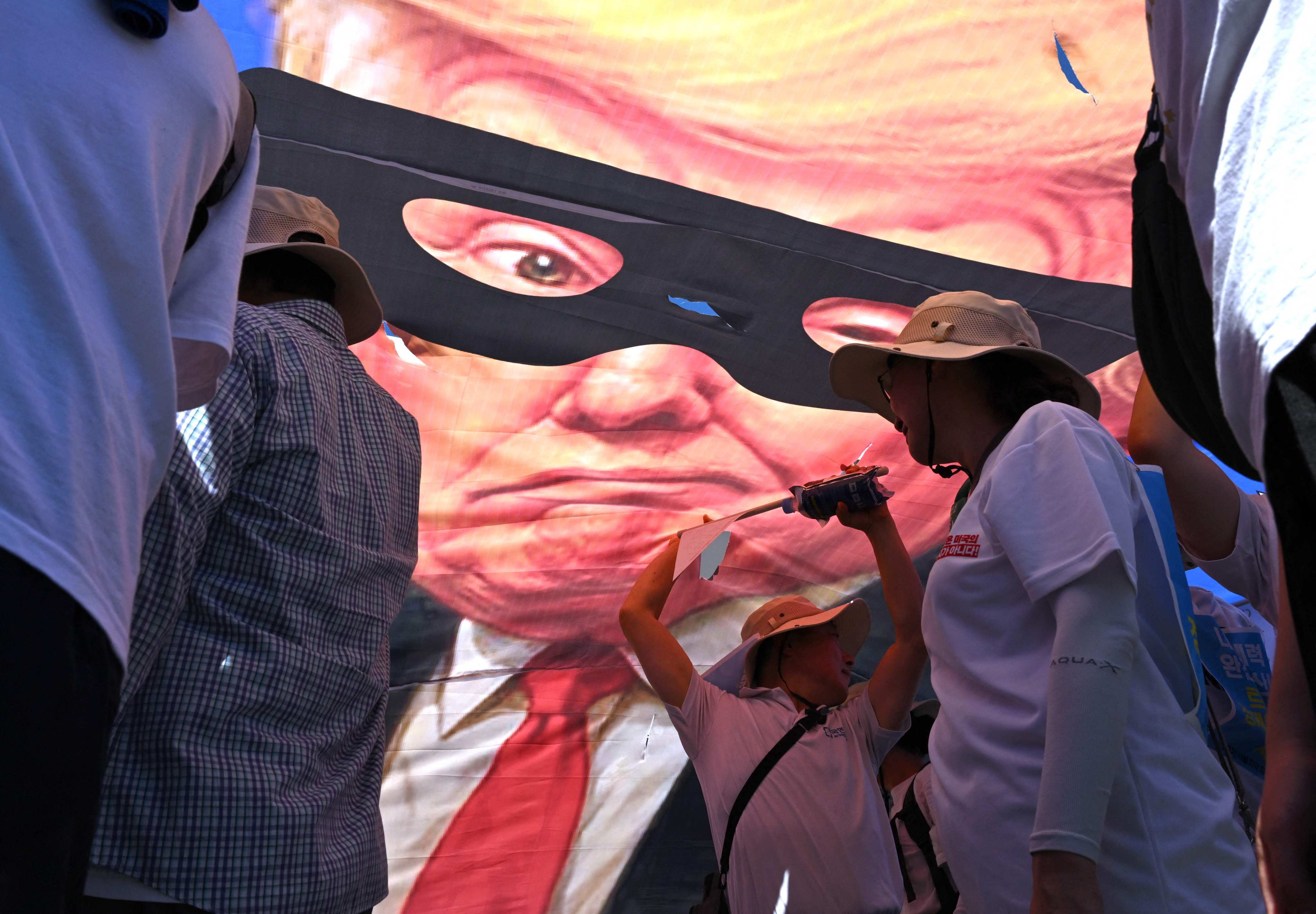

Analysts say Washington has been increasingly explicit in its demands for allies to shoulder more defence responsibilities under US President Donald Trump.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

“Trump explicitly demands the sharing of roles, responsibilities and burdens from allies and friendly nations,” said Park Won-gon, chairman of the East Asia Institute’s North Korea Studies Centre, in a recent commentary.

The call for greater burden-sharing was reinforced at May’s Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, where US Secretary of Defence Pete Hegseth said it “makes no sense” for Asian nations exposed to North Korean and Chinese threats to spend less on defence than their Nato counterparts. South Korea spent around 2.8 per cent of its gross domestic product on defence last year – far below the 5 per cent pledged by some European allies.

Hegseth further warned against “seeking both economic cooperation with China and defence cooperation with the United States”, which he said was becoming increasingly untenable.

“Economic dependence on China only deepens their malign influence and complicates our defence decision space during times of tension,” Hegseth said. “Nobody knows what China will ultimately do, but they are preparing. And therefore we must be ready as well.”

US forces’ expanding role

Under this evolving paradigm, US forces stationed in South Korea – currently numbering some 28,500 – may see their role expand from deterring Pyongyang’s military to broader operations across the Indo-Pacific, including potential contingencies in the Taiwan Strait.

Speaking at a symposium in Hawaii in May, US Forces Korea Commander General Xavier Brunson reportedly described South Korea as “a fixed aircraft carrier floating between Japan and mainland China”.

Stressing the strategic necessity of a continued US ground presence on the Korean peninsula, he told the US Army’s Land Forces Pacific Symposium that “the mission of USFK is not solely focused on North Korea”, signalling a shift in the military command’s traditionally narrow focus.

Against this backdrop, regional cooperation is also deepening. The US, South Korea and Japan have been exploring closer missile defence integration and intelligence sharing, moves analysts say are aimed squarely at countering China’s growing military reach.

But this evolving alliance comes with its costs. In his commentary for the East Asia Institute, Park argued that the Trump administration’s strategy linking economics and security “imposes a substantial burden on US allies”. For South Korea – directly threatened by Pyongyang and economically intertwined with both Washington and Beijing – that challenge is most acute.

“South Korea stands at a crossroads of choices more arduous and momentous than ever,” Park wrote. This was especially true as the USFK’s focus started shifting from “deterring North Korean threats to cover the Indo-Pacific region, targeting China”, he added.

Military strategists say US forces stationed in South Korea are more vulnerable to Chinese attacks than those deployed elsewhere such as Japan, which offers a more defensible staging ground for regional power projection.

In recent months, Washington has reportedly been pressing South Korea to apply their mutual defence treaty to any possible Taiwan Strait crisis.

One article of their treaty does stipulate that an armed attack “in the Pacific area” is to be treated as a mutual threat.

But Seoul, for its part, says it has neither accepted nor rejected such a demand.

In a televised debate before he took office, South Korea’s newly elected President Lee Jae-myung, who self-identifies as a pragmatist, emphasised the need for balance.

“We shouldn’t exclude or antagonise China and Russia. Diplomacy must always prioritise national interest and be approached pragmatically,” he said.

When pressed on whether South Korea should intervene in a potential Taiwan Strait conflict, Lee was unequivocal: South Korea should prioritise its own “national interests” and avoid being drawn in, he said.

But that might be easier said than done. “As long as Seoul remains unable to clearly define its position on USFK’s role in a Taiwan contingency, its direct involvement remains a matter of speculation,” Koh said.