Re-elected Albanese heads to Indonesia first, signalling Australia’s Southeast Asia focus

The prime minister’s visit to his ‘good friend’ Prabowo shows that the region is central to Australia’s foreign policy agenda, experts say

Fresh from re-election, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is making Indonesia his first overseas stop, a move analysts say underscores Canberra’s intent to place Southeast Asia at the centre of its foreign policy while repairing earlier diplomatic missteps and navigating rising geopolitical tensions in the region.

Albanese will fly into Jakarta for a two-day visit beginning Wednesday to attend the Australia-Indonesia Annual Leaders’ Meeting, according to the Indonesian Foreign Ministry on Monday.

“The visit will be PM Albanese’s first visit after he was reelected and it shows the strategic closeness of both countries,” spokesman Rolliansyah “Roy” Soemirat said.

Australia and Indonesia upgraded their relations to a Strategic Comprehensive Partnership in 2018 and forged the Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement in 2019.

During this week’s meeting, both leaders are expected to discuss increasing bilateral economic cooperation including in food, energy resilience and trade.

In an earlier interview with local media, Albanese said Australia had “no more important relationship than Indonesia”, describing President Prabowo Subianto as a “good friend of mine on a personal level”.

Abdul Rahman Yaacob, a research fellow at the Lowy Institute’s Southeast Asia programme, said the visit reflected Canberra’s desire to maintain its focus on Southeast Asia and was a sign that it valued its relations with Indonesia.

“Albanese had missed Prabowo’s inauguration in October 2024, and that was a misstep,” he said.

The visit was also a signal that relations were not affected by Russia’s recent request for access to an Indonesian airbase, he added.

Last month, Jakarta dismissed reports of a Moscow proposal to base several of its aircraft at an Indonesian Air Force base in Papua – news that rang alarm bells in Canberra. Indonesia has made it clear that it will not allow any foreign military bases in the country.

Sending a strong message

Gatra Priyandita, a senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute think tank said that traditionally, Australian prime ministers had chosen Indonesia as their first state visit to signal its deep ties to Asia, particularly Southeast Asia.

“By visiting Jakarta first, the government reinforces its message that regional partnerships are not secondary to relations with major powers, but central to Australia’s foreign policy agenda,” Gatra said.

During the visit, both countries are likely to pledge to intensify diplomatic, security, and economic ties, building on a historic defence cooperation agreement signed last year as well as growing trade and investment ties.

In August, the two nations signed an agreement allowing for greater cooperation and interoperability between their defence forces in maritime security, counterterrorism, humanitarian and disaster relief.

Between 2019 and 2024, Australia ranked as the 10th largest investor in Indonesia, with a total investment of US$2.7 billion with mining, hospitality, real estate and industrial estates being the top sectors.

Canberra has implemented the Southeast Asia Economic Strategy aimed at increasing two-way trade and investment. It also established the Office of Southeast Asia within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and “significantly increased” diplomatic and defence engagement with key regional partners including Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines, Gatra noted.

Last month, Canberra said it would double military training activities under the Joint Australian Training Team-Philippines programme this year.

Among Southeast Asian defence and foreign affairs officials, there was broad appreciation of Canberra’s renewed engagements with the region and measured relations with China, Rahman said.

Albanese is also likely to visit other Southeast Asian countries – particularly Singapore as this year marks the 60th anniversary of Australia-Singapore diplomatic ties. Both sides are said to be working on a new strategic partnership.

During the pandemic years, ties between Beijing and Canberra sank to new lows after Australia called for an independent investigation into the origins of the epidemic that first witnessed a major outbreak in China.

Beijing also imposed trade restrictions on a range of Australian agricultural and mineral products.

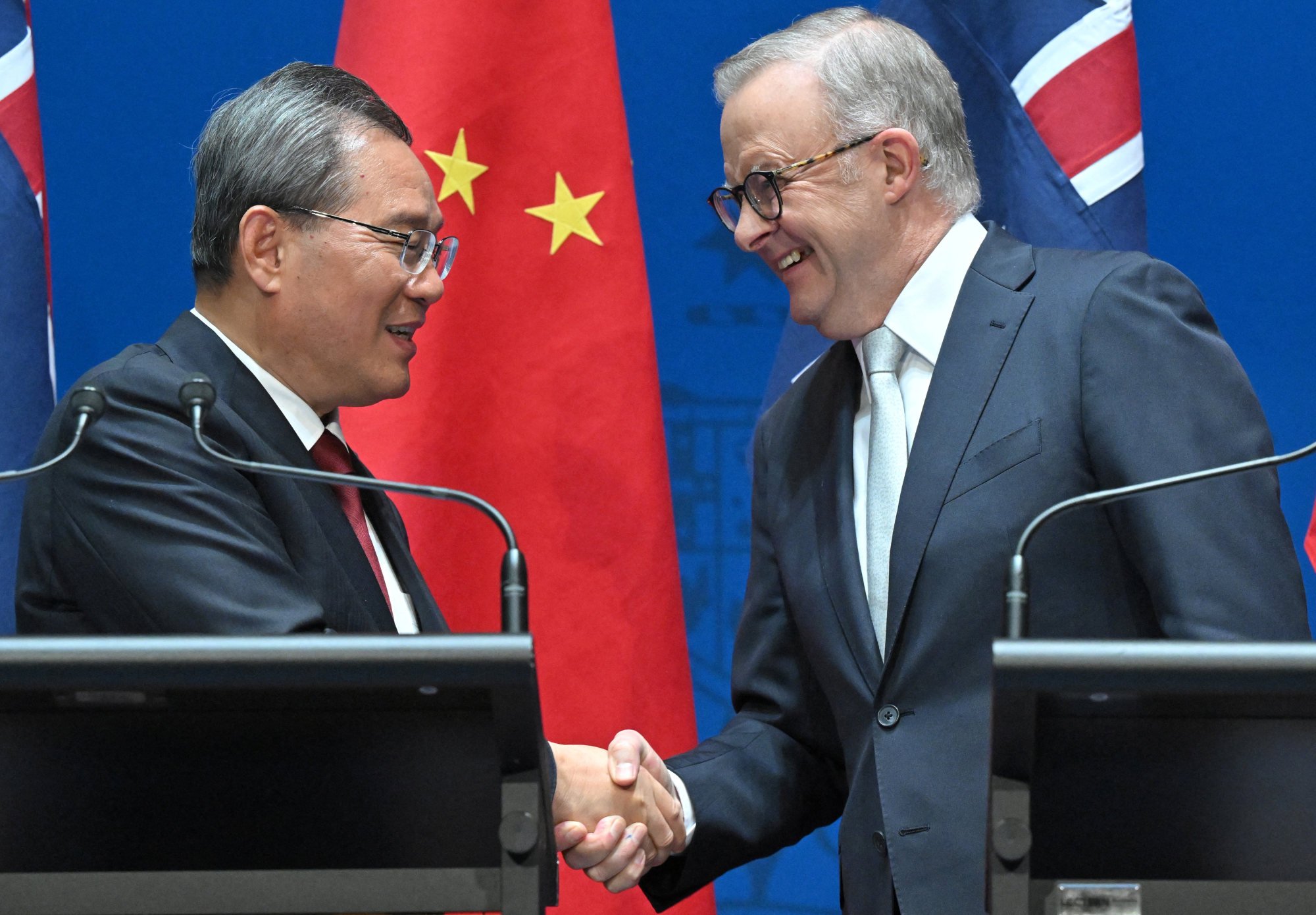

But relations were “back on track”, according to Chinese Premier Li Qiang after a visit to Australia last year.

Trade restrictions had eased by then and Albanese – during his first term in office – had also adopted a softer diplomatic approach to Beijing.

Challenges in Southeast Asia

As for the broader Southeast Asian region, Gatra said Australia would continue to intensify economic, diplomatic, climate, energy and security links with the region.

“[These will be] tailored to the diverse needs and strategic priorities of individual Southeast Asian states,” he said.

He added that a major challenge facing Australia was how it would manage perceptions of its close security links with the United States “without undermining its credibility as an independent and trustworthy partner to Southeast Asia”.

Canberra and Washington cooperate both bilaterally and through regional groups such as the Quad, or the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue. The two countries also conduct routine joint military exercises.

Anxious about the US-China rivalry, Southeast Asian countries have often expressed reluctance in picking a side.

Southeast Asian states generally perceive Australia as being interested in the region primarily from a security perspective. These include implementing the 2020 Defence Strategic Update focusing on maritime Southeast Asia and the 2024 National Defence Strategy which point towards the region as an important one for Australia.

“Australia should engage the region more on non-security areas – such as digitalisation, investment and clean energy while working on to improve people-to-people connections,” Rahman said.

Some in Australia have also argued that Canberra should “engage less” with Southeast Asia as the region did not share Australia’s stance on China and the Ukraine war, he added. There was criticism when Malaysia and Indonesia joined Brics, for instance.

“That is a strategically wrong approach which could potentially maximise the number of regional states turning against Australia,” Rahman said.

It also reflected a lack of understanding of Southeast Asia’s nuances on strategic issues, which was to establish friendly relations with all parties.

“Canberra must understand that Southeast Asia will not completely share Australia’s security concern, but that does not mean the two parties could not cooperate and work together on areas of common interest.”