Philippines’ US security blanket muffling hopes of strategic autonomy

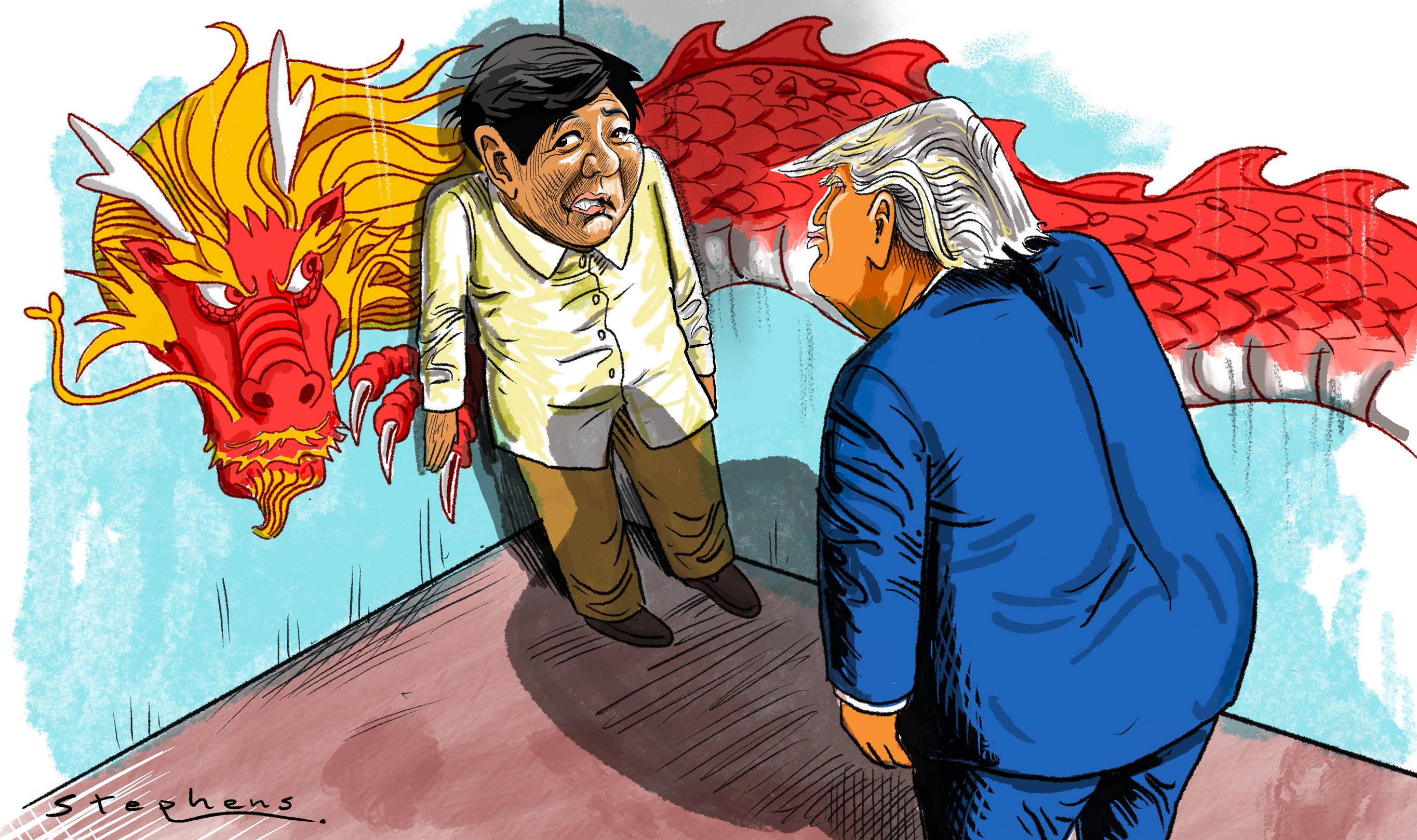

Marcos’ goal of a balanced foreign policy is at odds with efforts to further intertwine the US and the Philippines in the security sphere

Since coming to power earlier this year, US President Donald Trump has broadly signalled a historic departure from America’s traditional role in global affairs. Not only has the US decoupled from global institutions such as the World Health Organization, it has disrupted international trade by adopting an aggressively protectionist stance through the imposition of massive tariffs on foes and friends alike.

The same unorthodox approach has also characterised the second Trump administration’s approach to its overseas military commitments. From scaling back much-needed defence aid to Ukraine to berating European allies on defence spending, the second Trump administration has ushered in a new era of American foreign policy. When it comes to Asia, however, the US has shown remarkable policy continuity.

This is most notable in the case of the Philippines, which has become a critical ally amid Washington’s deepening rivalry with China. Far from abandoning Manila, the Trump administration and its legislative allies are doubling down on defence aid to, and military cooperation with, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr’s administration.

Aside from deploying state-of-the-art weapons systems and establishing new military facilities in the Philippines, the Pentagon is also mulling the establishment of a regional munitions hub in Subic Bay. Though no formal proposal has been submitted by the Trump administration yet, with the US Congress still reviewing the plan, top Philippine defence officials have welcomed greater US forward deployment presence in Asia.

Though greater defence assistance from Washington is critical to Manila’s ability to protect its core interests in adjacent waters, it could come at the expense of the Philippines’ efforts to develop strategic autonomy.

Early in his tenure, Marcos underscored his commitment to a balanced relationship with the global superpowers. While continuing to mend frayed ties with Washington after years of an acrimonious relationship during the early years of Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency, he also placed constructive ties with China at the heart of his foreign policy. After all, the Marcos family has a historically warm relationship with Beijing.

During his presidential campaign, Marcos negotiated a tactical alliance with the Duterte family, choosing the outgoing president’s daughter Sara Duterte as his running mate. While doing so, he publicly expressed support for the elder Duterte’s soft stance on territorial disputes in the South China Sea in the interest of maintaining regional peace.

Shortly after securing the presidency, Marcos vowed to elevate bilateral relations with China during a phone conversation with President Xi Jinping. Just months later, he portrayed Beijing as his country’s “strongest partner” and a “close neighbour” and a “good friend”. Similar to his predecessor, Marcos chose China as his first major destination outside Southeast Asia, where he signed 14 agreements and secured US$22.8 billion worth of investment pledges.

Deadlock over the South China Sea disputes and simmering resentment over unfulfilled Chinese infrastructure investment pledges, however, made Marcos more open to the West’s overtures. Eager to enhance the Philippines’ leverage, he welcomed expanded defence ties with traditional partners.

This culminated in growing Japan-Philippine-US security alignment, a reciprocal access agreement with Japan and, most crucially, an expanded Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement (EDCA). This latter agreement paved the way for greater US military presence across strategically located Philippine provinces, including those close to Taiwan’s southern shores.

Even so, Marcos has tried to maintain a balanced foreign policy, with even top US officials remaining adamant they don’t want regional states to choose between the competing superpowers. Accordingly, Manila maintained institutionalised dialogue with Beijing in spite of rising tensions in the South China Sea and denied that new EDCA bases in northern Philippine provinces would be used for offensive operations in the event of conflict in neighbouring Taiwan.

However, the Philippines has steadily moved away from strategic hedging during the past year in favour of closer alignment with the US. Shortly after US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth’s visit to Manila – during which he reiterated the urgency of enhancing joint deterrence capabilities against “Communist China’s aggression in the region” – the two allies conducted large-scale drills in the South China Sea and near the Bashi Channel off southern Taiwan.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

During this year’s Balikatan exercises, the two allies simulated full-scale war scenarios, deploying more than 14,000 service members between them as well as advanced weapons systems such as the Navy-Marine Expeditionary Ship Interdiction System missile launcher. The Trump administration raised the stakes by also mulling the possible deployment of a second Typhon mid-range missile system to the region after having semi-permanently stationed one in the northern Philippines.

The proposed munitions manufacturing and storage facility in Subic Bay could serve as a crucial accelerator for the local defence industry in the Philippines under the new Self-Reliant Defence Posture Revitalisation Act.

Technology transfers and an integrated defence supply chain with the US would also enhance the Philippines’ ability to negotiate big-ticket military acquisitions, including modern US fighter jets. Ultimately, it would also be indispensable to the US effectively conducting any large-scale, protracted military showdown with China over either Taiwan or in the South China Sea.

This could serve as a deterrent against China’s territorial ambitions. However, the deepening military entwinement between the US and the Philippines could come at the expense of the Marcos administration’s ability to establish a more autonomous foreign policy in the long run, as well as the risk of being dragged into war against China. Halfway through his presidency, Marcos finds himself at a strategic crossroads unlike that faced by any of his predecessors.