Philippines’ Marcos offers reconciliation with Dutertes – will it work?

Marcos’ offer comes after a series of politically charged developments and is seen as a bid to boost his declining approval ratings

President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr has called for reconciliation with Vice-President Sara Duterte-Carpio and her family, despite moves by his administration and political allies to impeach her and send her father to face trial in The Hague – a dramatic shift observers say could reflect either political vulnerability or strategic calculation.

In a one-on-one interview with broadcaster Anthony Taberna aired on Monday, Marcos was asked directly: “Mr President, in your heart do you want to reconcile with the Duterte family?”

The president replied, “Yes. Personally, I don’t want conflict. I want to get along with everyone. That’s better. I already have many enemies and I don’t need enemies. I need friends.”

His surprising comment came just days after Duterte-Carpio said she welcomed her Senate impeachment trial – initiated by House Speaker Martin Romualdez and Representative Sandro Marcos, the president’s cousin and son respectively – saying she looked forward to “a bloodbath”.

It followed a string of politically charged developments: the electoral defeat of most of Marcos’ senatorial candidates in the May 12 midterms; the March 11 transfer of Duterte-Carpio’s father, former president Rodrigo Duterte, to The Hague to face trial for alleged crimes against humanity; and the February 5 vote by the House of Representatives, led by Romualdez, to impeach the vice-president.

While Marcos’ offer of reconciliation has dominated local headlines, there has been no public response from the Duterte family.

However, Salvador Panelo, who served as Duterte’s chief presidential legal counsel, posted on Facebook that “if he brings back the former president to the Philippines then there will be reconciliation”.

“All [Marcos] has to do is to tell the International Criminal Court [ICC] that his people made a mistake in arresting, detaining and sending to the jail the former president and he is correcting it by asking them to bring him back. And I think that will be a very important reconciliation gesture,” Panelo pointed out.

But University of the Philippines political science professor Jean Franco dismissed such a move as symbolic at best.

“It is too late because the impeachment [of Duterte-Carpio] and the arrest and trial of Duterte are already in progress,” Franco told This Week in Asia.

Franco also said the offer was “maybe” sincere on the president’s part, “but the motivation it seems is his declining approval ratings”.

Ahead of the May 12 election, Marcos’ approval ratings tracked by private pollster Pulse Asia had plunged 17 percentage points from 42 per cent in February to 25 per cent in March.

In contrast, that of Duterte-Carpio rose seven percentage points from 52 per cent to 59 per cent during the same period.

According to Professor Walden Bello, a political risk analyst and former congressman, the test of the president’s sincerity is “if he gets his allies in the House to withdraw the impeachment” of his vice-president.

Bello described Marcos’ offer as “not an olive branch but a white flag of surrender”.

He told This Week in Asia: “The Dutertes’ price for peace is the return of Duterte from The Hague. But that won’t happen without the ICC losing credibility. And without provoking a huge outcry from a large sector of the country concerned with human rights and due process.”

Historian Manolo Quezon offered a more cynical take on Marcos’ apparent change in tone, drawing a parallel with the political tactics of his father, the late Ferdinand Marcos Snr.

He cited how Marcos Snr had managed a similar feud with then vice-president Fernando Lopez. According to Quezon, Marcos Snr “bought time by suddenly brokering a truce with the Lopezes”, allowing Lopez to remain in high-level meetings with congressional leaders even after the declaration of martial law.

At the time, a constitutional convention was under way to replace the 1935 Philippine constitution. Quezon noted that Lopez “sat in on the meeting with congressional leadership planning the campaign to approve the 1973 constitution even after martial law was imposed”. Ironically, the 1973 constitution would ultimately abolish the vice-presidency and remove him from the line of succession.

Historical records show that the truce between the Marcos and Lopez families lasted only long enough for Marcos Snr to consolidate power. After imposing martial law in 1972, he turned on the Lopez clan – shutting down their radio, television and newspaper outlets, seizing their assets, jailing Lopez’s nephew Eugenio Jnr, and accusing Lopez himself of involvement in an assassination plot.

In a similar vein, Marcos Jnr campaigned in 2022 alongside Duterte-Carpio on a platform that included replacing the 1987 Philippine constitution – a charter enacted after the fall of his father’s regime.

But Bello questioned whether the president had the political resolve to see such a plan through.

“I don’t think Marcos Jnr has either the smarts or the determination to pursue a long, drawn-out fight. He has neither the ruthlessness nor the cunning of his father,” Bello said.

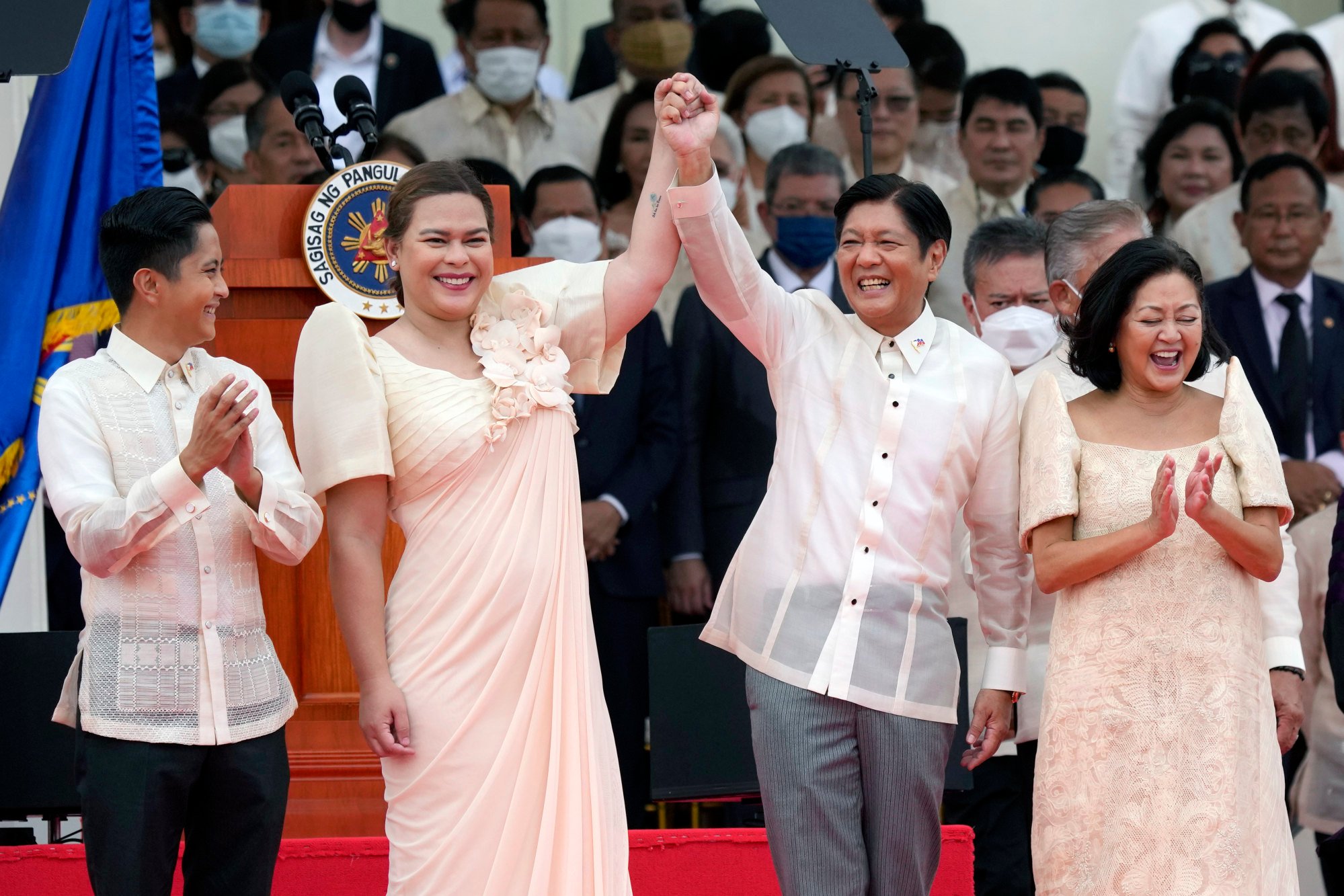

Marcos and Duterte-Carpio swept to power in 2022 under their so-called Uniteam banner. But cracks began to appear a year later, when Duterte-Carpio lashed out at Speaker Romualdez, calling him a tambaloslos – a gluttonous creature from local folklore.

Tensions deepened in June 2024, when she resigned from the cabinet after the president’s wife, Marie Louise, publicly rebuked her for laughing at a rally where her father, former president Duterte, had called Marcos bangag – a slang term suggesting he was drug-addled.