Pakistan’s bitcoin reserve plan aims to turn energy surplus into tech investment

The strategy to diversify the economy and hedge against currency volatility carries high risks, but the rewards could be great, analysts say

Following in the footsteps of US President Donald Trump’s administration, Pakistan plans to create a sovereign bitcoin reserve powered by unused electricity in a bold bid to monetise its energy oversupply and attract foreign tech investors.

Analysts warn that the high-risk strategy could strain Pakistan’s fragile power grid, raise red flags with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and expose Islamabad to cryptocurrency market volatility. However, some argue it could also help diversify the economy and hedge against currency instability, if managed well.

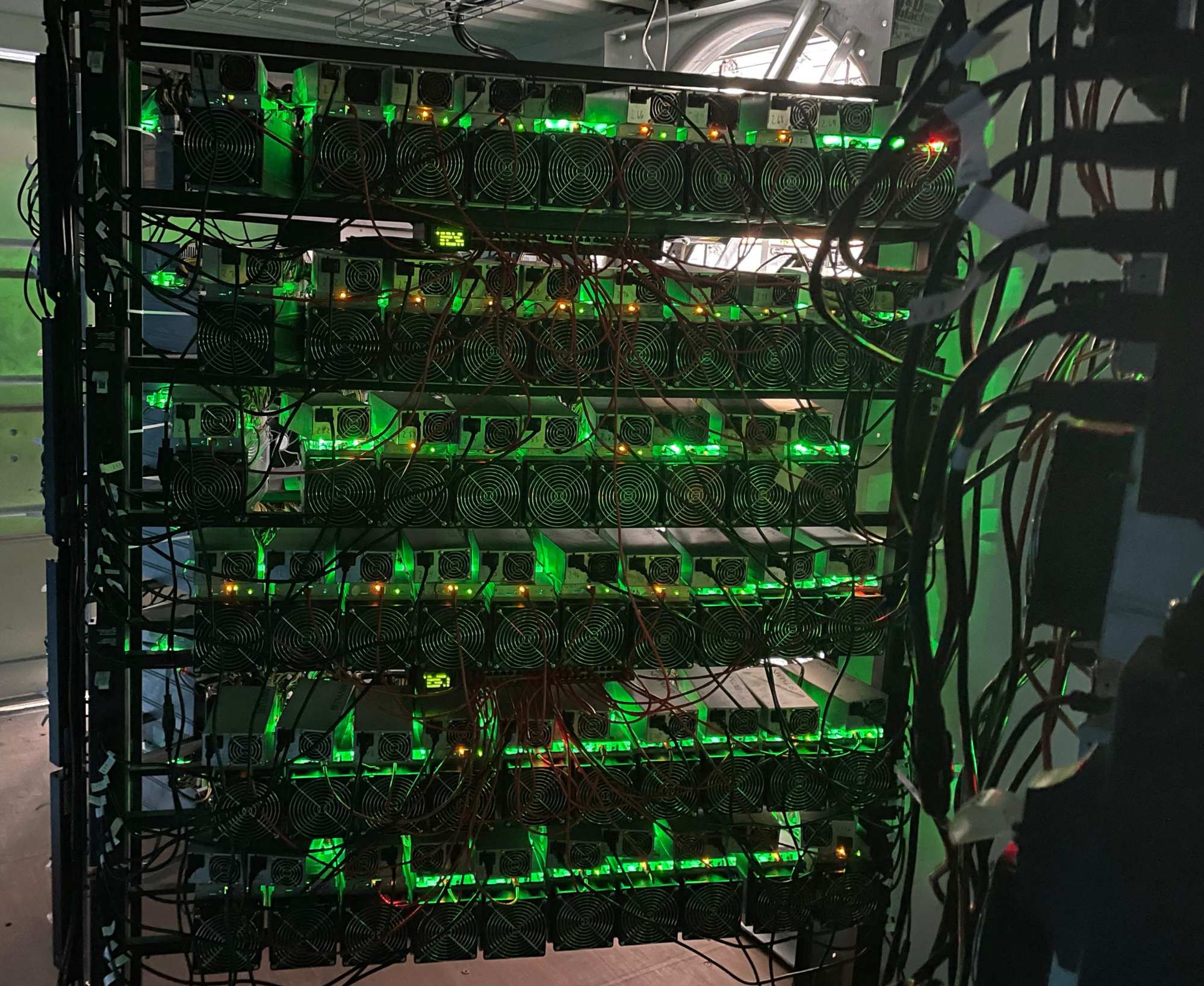

The official Pakistan Crypto Council (PCC), set up in February and led by British-Pakistani tech entrepreneur Bilal bin Saqib, will offer 2,000 megawatts of spare power plant capacity to attract foreign bitcoin miners and artificial intelligence data storage centre investors.

Its first client is set to be World Liberty Financial (WLF). The stablecoin firm that is majority owned by the Trump Organisation signed a letter of intent with the PCC on April 26 to “accelerate blockchain innovation, stablecoin adoption and decentralised finance integration across Pakistan”.

Their envisioned scope of cooperation includes the launch of “regulatory sandboxes” for blockchain financial product testing, easing the “responsible growth” of decentralised finance protocols and exploring the tokenisation of real-world assets like real estate and commodities.

They also plan to expand stablecoin applications for remittances and trade – opening up the possibility of Pakistan using WLF’s stablecoin USD1, which is issued on Binance’s blockchain.

Saqib, who was last month given a minister of state status by Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, announced the initiative on May 29 at The Bitcoin Conference attended by Donald Trump Jnr, Eric Trump and WLF CEO Zachary Witkoff – son of the US president’s Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff.

In his speech, Saqib said that Pakistan had established a national bitcoin wallet “holding digital assets already in state custody – not for sale or speculation, but as a sovereign reserve signalling long-term belief in decentralised finance”.

Pakistan’s government began the process of reviewing proposals for a regulatory framework on Monday, “aiming to align it with international standards and evolving technological trends”, according to an official statement.

They included “an autonomous regulatory authority to oversee and regulate the digital finance and cryptocurrency ecosystem in the country”.

Finance Minister Muhammad Aurangzeb said the government was committed to creating a “future-ready financial infrastructure that supports innovation while maintaining financial stability and regulatory compliance”.

As the largest holder of USD1 and an adviser to WLF, Hong Kong cryptocurrency entrepreneur Justin Sun stands to benefit from the firm’s deal with Pakistan. Earlier in April, WLF announced that USD1 would be integrated into Sun’s Tron blockchain.

Binance founder Zhao Changpeng is another PCC key adviser. Like Saqib, he wears two hats and was also appointed a WLF adviser in April.

Cryptocurrency hurdles

Pakistan would have to overcome numerous challenges to succeed as an early bird adopter of the strategic bitcoin reserve model launched by the Trump administration, fintech experts say. These range from offering competitive prices to overcoming objections from key lender the IMF.

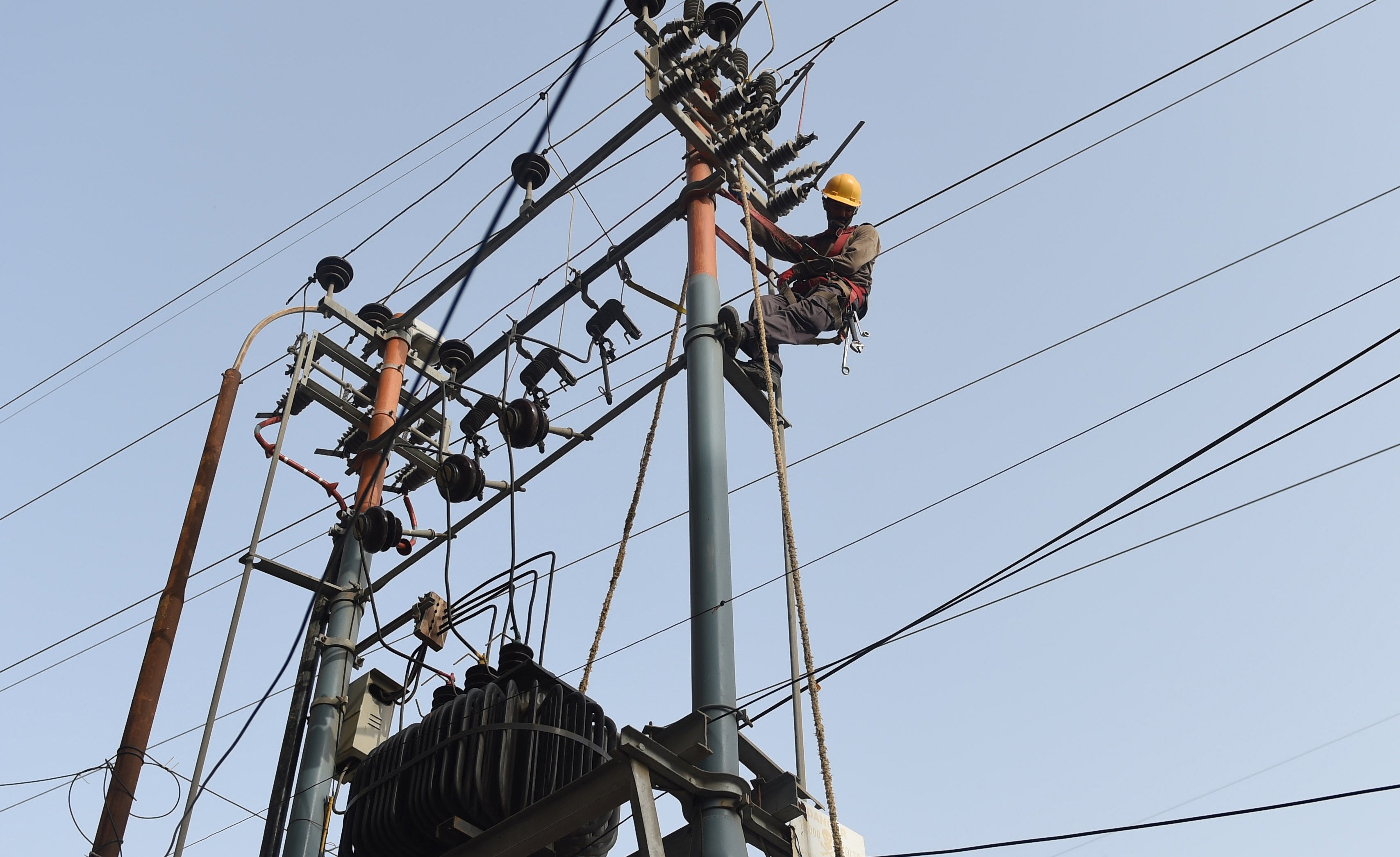

“Significant hurdles related to energy infrastructure and the potential strain on an already challenged power grid, coupled with concerns about the volatility of the cryptocurrency market, make it a high-risk endeavour,” said David Krause, an associate professor of finance at Marquette University who recently published a study of WLF.

Krause said he was “generally sceptical, much like the IMF, about its viability”.

Even if Pakistan’s reserve was not actively traded, its economic benefit was based on long-term appreciation and the ability to attract related industries.

Pakistan’s “never-sell approach means forgoing immediate liquidity and exposes the country to bitcoin’s inherent volatility, which still remains relatively high”, he said. Bitcoin was a non-earning asset and, therefore, “the time value of money works against them”.

“Should the value of bitcoin decline or mining prove unsustainable, this strategic reserve, instead of being an asset, could become a significant liability.”

Bitcoin Association Pakistan partner Luqman Khan was more optimistic. Islamabad stood to earn about US$1 billion in annual revenue by redirecting 2,000MW of unused power – assuming that bitcoin prices stabilise around US$100,000 and mining operations achieve over 90 per cent uptime, he said.

Pakistan’s government pays about US$2.5 billion a year in capacity charges to independent power producers for unused electricity under “take-or-pay” agreements.

That meant Pakistan’s surplus power capacity of 10,000 to 15,000MW was “essentially free in the sense that it’s already paid for through capacity charges”, Khan said. “Mining with this excess could turn a liability into a revenue stream.”

Playing the long game

A non-tradeable bitcoin reserve was primarily about long-term economic positioning, Khan said. It would act as a hedge against currency instability, given how the Pakistani rupee has depreciated by over 50 per cent against the US dollar in the last five years.

With inflation averaging between 12 and 15 per cent annually, a reserve currently valued at over US$100,000 per bitcoin would offer a “store of value immune to local monetary pressures”.

By accumulating 10,000 bitcoin, a modest US$1 billion reserve at current prices, Pakistan could “stabilise its balance sheet against future currency shocks, much like gold reserves do but with higher growth potential”, Khan said.

He hoped a government-backed reserve could attract US$500 million to US$1 billion in foreign investment into bitcoin start-ups and infrastructure.

Over a decade, a bitcoin-backed digital economy could boost Pakistan’s small gross domestic product of around US$300 billion, Khan said. “It’s a long game and the payoff is structural transformation.”

Benjamin Grolimund, general manager of cryptocurrency trading platform Flipster, described Pakistan’s bitcoin gambit as a “fascinating undertaking of the interplay between energy economics, monetary policy and tech ambition”.

While showing a forward-thinking approach, “it’s worth sounding caution in balancing power-price economics” because bridging traditional finance and cryptocurrency “demands realism”, he said.

Pakistan’s current power generation tariff of 7 US cents per kilowatt hour for bitcoin mining is much higher than the 1 to 3 US cents per kWh of leading mining destinations like Texas.

While this gap could be bridged with operational innovation, “pulling this off hinges on sophisticated technical integration and private capital deployment at scale – capabilities that are arguably still under major development”, he said.

Pakistan’s government might have to adopt a public-private partnership model in which it would share the capital expenditure cost of ventures with cryptocurrency mining operators, said Ali Farid Khawaja, chairman of Karachi-based financial services firm KTrade.

Khwaja was confident Pakistan’s plan would work, citing first-hand knowledge that companies from Britain, China, Canada, Singapore, the UAE and the US “are approaching, expressing interest and keenness to invest and get involved”.

Pakistan’s strategy was not “Trump-specific” and it had been engaging with “all leaders in this space”, including Michael Saylor of Strategy and Cathie Wood of ARK Invest.

While it was “heartening to see” that a leading firm like WLF was interested in Pakistan, “I am sure that you will see other digital asset leaders in Pakistan soon as well,” Khwaja said.