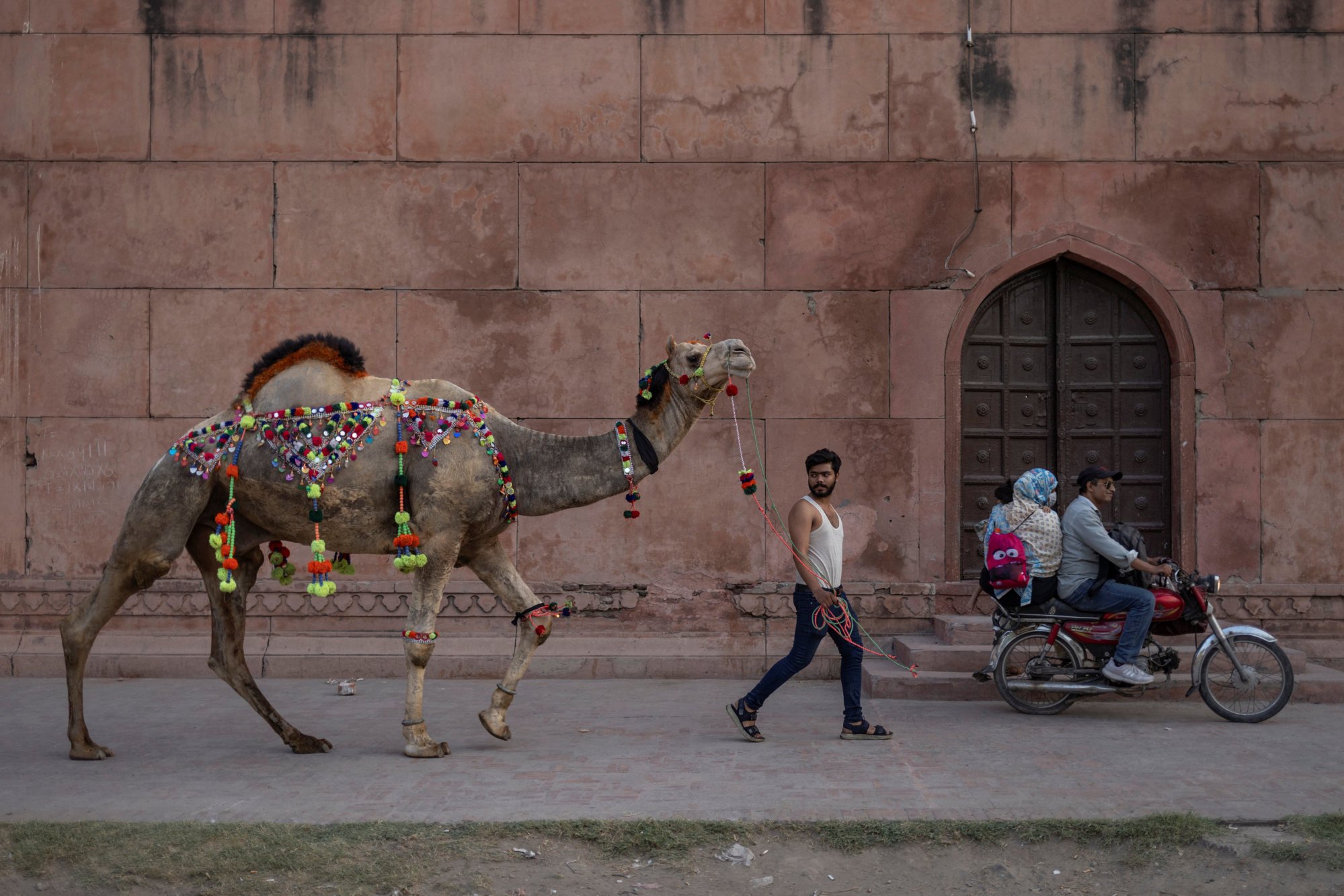

Pakistan’s animal army marches to markets for haggling at annual festival

For livestock farmers across Pakistan, the Muslim festival of Eid al-Adha is an opportunity for them to make good money

Once a year, Pakistanis mobilise for an operation that is akin to a major battle taking place in terms of scale and blood being spilled.

Much is at stake – at least financially – as veritable four-legged armies numbering hundreds of thousands march on Pakistan’s population centres from farmsteads around the country.

For the livestock farmers leading the sieges, the deals cut at pop-up markets for sacrificial bulls, goats and sheep – along with the occasional camel – on the Muslim festival of Eid al-Adha determine if their efforts over the last six months or so were worthwhile.

The vast majority of breeders are either sharecroppers or own small landholdings barely capable of turning a profit, and many live below the poverty line. They spend half the year raising small flocks and herds for Eid al-Adha to supplement their limited income.

However, Pakistan’s livestock herds are vulnerable to natural disasters and poor farming practices.

An estimated 1.1 million farm animals were killed by the Indus river superfloods in 2022, which inundated a third of Pakistan.

Viruses like foot-and-mouth disease and lumpy-skin disease periodically wipe out herds left unvaccinated by poor, illiterate farmers.

Official statistics show how important livestock is to Pakistani farmers, who make up more than 37 per cent of the country’s 72 million-strong workforce.

Although animal husbandry is a part-time activity for most cultivators, it accounts for about 61 per cent of overall agricultural income and 15 per cent of gross domestic product.

This is reflected by the number of sacrificial beasts that descend on Pakistan’s cities every Eid al-Adha. The country’s largest organised livestock market, located on the outskirts of Karachi, a seaport city of over 20 million residents, has attracted about 800,000 animals this year, officials say.

The administrations of all major Pakistani cities have erected such livestock markets in recent years, partly to discourage the traditional practice of sellers roaming the streets with their dung-dispersing animals in search of customers.

Money is a major motivator for municipalities, whether it is collected as rent for paddocks to hold livestock, deducted as a roughly 10 per cent cut of sale proceeds, or extorted by officials as bribes for the return of animals seized from unauthorised markets.

Many sellers still prefer to run the gauntlet and set up impromptu stalls on roads linking major city roads to suburban gated communities housing well-off families capable of purchasing one or more sacrificial animals to fulfil their religious obligation of Eid al-Adha.

A recent visit to one such market on the southern periphery of Islamabad by This Week In Asia was an assault on the senses: crowds of loud-talking people, honking vehicles and animals jostling for space on the roadside as shoppers browsed animals and bargained with sellers.

Their negotiations followed a long-set pattern wherein sellers would typically quote a highly inflated price, prompting “shocked” buyers to offer about one-third of the quoted rate. Both sides eventually agree on a going market rate – except for the odd customers who are either clueless about the fair price or could not be bothered to haggle.

A well-heeled man in his 30s, dressed in a polo shirt and long shorts, approached a group of farmers to buy a floppy-eared speckled white goat, which his young son had taken a liking to.

He made little headway at first as the farmers, dressed in baggy shalwar-kameez suits, stuck to their guns: 60,000 Pakistani rupees (US$212) was the price, take it or leave it.

Mumbling annoyedly, the prospective customer began to walk away but was intercepted by a well-spoken young man, who began to act as a middleman between the Urdu-speaking city dweller and the Seraiki-speaking farmers.

Within minutes, they settled on a price of 53,000 rupees, and the buyer’s happy son grabbed the goat’s chain and led it to their car and put it in the boot to take home.

The middleman Mohsin Niazi, it turned out, was the educated frontman for a group of 14 relatives from Bhakkar, an arid district located 350km southwest of Islamabad.

The seller Shakeel Ahmed was his uncle, and both were understandably pleased with the price they had got for the goat. They originally bought it in December for 30,000 rupees and fattened it with fresh and dried fodder harvested from their farm at a minor cost.

Every year, Niazi said, the family’s men would each raise small flocks of 10 to 15 goats and the odd bull to sell in the Pakistani capital. This year, they had brought 82 goats and a couple of cattle to sell in Islamabad, the nearest large city to Bhakkar.

Half the goats had been bought from local farms when they were kids aged two to three months. Fed for six months, these goats’ weight and value would often double by the time of each sale. The rest had been bought fully grown from local markets in Bhakkar at a discount.

“It’s a great business to be in,” Ahmed said. “As long as you own some farmland and know what you’re doing, you’ll make good money.”

But the smiles were soon wiped off their faces by the sudden arrival of a truck ridden by municipality officials seeking to confiscate animals from the illegal stalls.

Breeders and their animals fled into the forest of bushes flanking an adjacent railway line to evade the loss of their year’s investment.

Unlucky sellers besieged the officials, protesting that the seizure of their animals would render them penniless.

“You’ll get your animals back when you come to the main livestock market to claim them,” an official tried to assure them.

An angry young breeder, who had six goats confiscated, retorted: “How the hell are we supposed to recognise them?”

He then proposed: “Come on the other side of the road so we can talk privately.”

The official followed, a deal was apparently struck, and the goats returned soon after.