Need a grandma? In Japan, you can rent one and help an old lady out

For US$20 an hour, these surrogate grandmothers are ready to offer services ranging from practical help to emotional support

“Grandma rental” services have caught on in Japan, providing an alternative source of income for the country’s ageing population seeking to alleviate the cost of living pressures amid rising inflation.

For 3,000 yen (US$20) per hour, clients are set up with a woman aged 60 to 94 who will help with requests ranging from teaching cooking skills to breaking up with partners on her client’s behalf, according to local news site SoraNews24.

The elderly women can also babysit and mediate family disputes, and some have even been called in to act as emotional support for couples breaking up or men coming out as gay to their parents. Others have provided insight for clients researching societal changes in Japan.

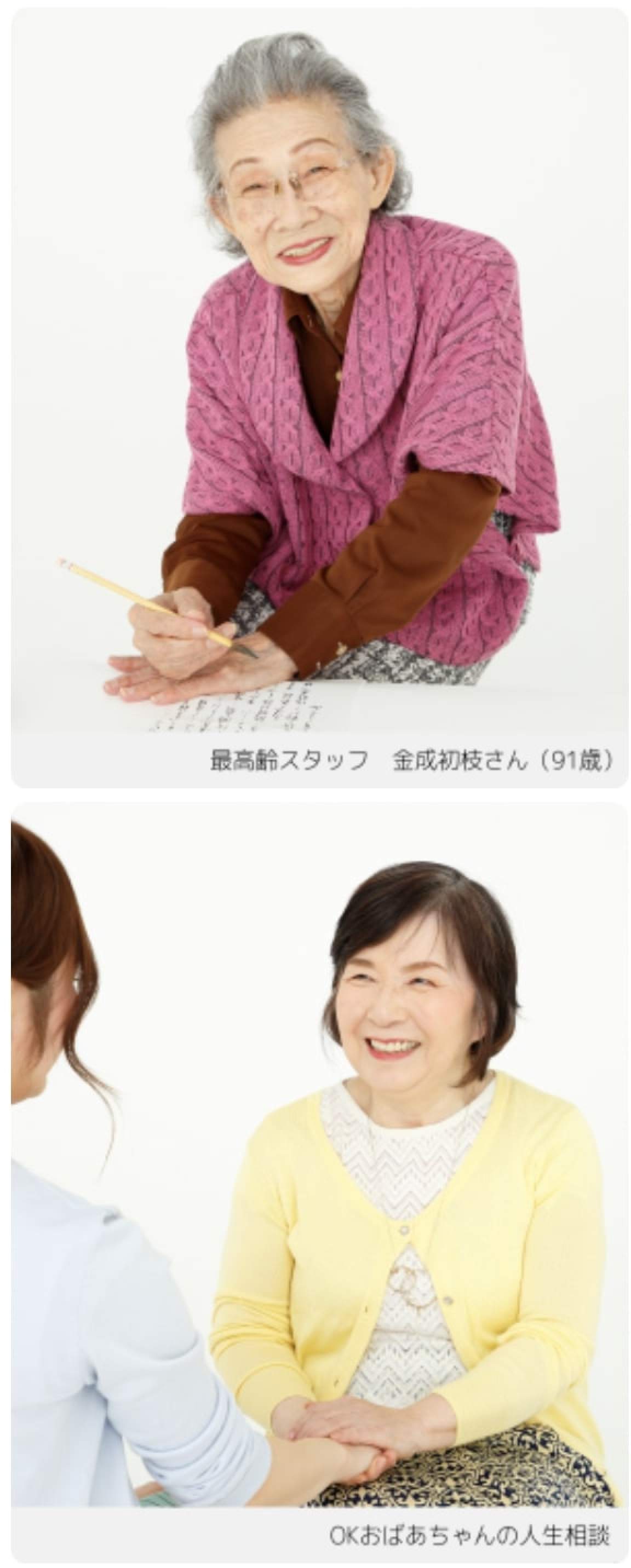

Called OK Obaachan (OK Grandma), this unique service currently has a roster of about 100 women who reportedly offer housework expertise, interpersonal skills and historical knowledge.

The service was launched in 2011 by a company called Client Partners, which, according to its website, is a “women-only handyman company” that sets women up with jobs from housekeeping to being a “talking companion”. Besides grandmas, the company also offers rental services for other female family members and friends.

In addition to the hourly fee, clients pay 3,000 yen to cover the women’s transport costs.

Japan’s “rent-a-family” industry has garnered attention in recent years, with rental services available for ossan (middle-aged men) as well as stand-in girlfriends and boyfriends.

‘Want income’

About 25 per cent of Japanese seniors remained employed last year, according to the government. The population aged 65 and above reached a record of 36.25 million as of September last year, making up almost one third of the population.

The rapidly ageing population has contributed to its severe demographic crisis, with births falling below 690,000 for the first time last year, 15 years ahead of predictions, the health ministry announced last month.

The country also faces a cost of living crisis. Persistent inflation has made making ends meet increasingly difficult – prices continue to rise faster than salaries, leaving workers with shrinking purchasing power.

In May, real wages declined 2.9 per cent from a year earlier, compared to economists’ consensus call of a 1.7 per cent fall, Japan’s labour ministry reported on Monday. That same month, Japan’s key inflation rate stood at 3.7 per cent, well above the central bank’s 2 per cent target.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

“Wanting income” was the main reason cited by more than half of older Japanese workers, while only 15.8 per cent said they were working because they found it interesting or fulfilling, Yasuo Takao, a research fellow at Curtin University’s School of Media, Creative Arts and Social Inquiry, wrote in the East Asia Forum last month.

Some have had to resort to desperate measures to survive. One 81-year-old Japanese woman, living on meagre pensions, deliberately shoplifted food so she could receive regular meals and healthcare for free in a women’s prison, according to a January report by CNN.