Japan’s low press freedom ranking signals self-censorship remains rife: analysts

Political pressure affects media coverage in Japan as journalists fear angering the government over their reporting, analysts say

Japan’s continuous low ranking for press freedom among the Group of Seven nations signals that it is still facing long-standing issues of political pressure, corporate influence and self-censorship in its media landscape, according to analysts.

The annual survey by Reporters Without Borders released on Friday ranked Japan 66th out of 180 countries and regions, up four places from last year. But Japan was still the lowest-ranked G7 nation and below developing countries such as the Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone and East Timor.

Some media analysts have expressed cautious optimism that Japanese news outlets might be recovering some of the editorial freedom lost over the past two decades, as younger journalists push back against restrictive norms and political control over the media shows signs of loosening.

Paris-based Reporters Without Borders, known by its French acronym RSF, described Japan as a parliamentary democracy where media freedom and pluralism are broadly respected, but it warned that “traditional and business interests, political pressure and gender inequalities often prevent journalists from completely fulfilling their role as watchdogs”.

Japanese governments have long been criticised for requiring members of the media to become part of a press club system if they want to attend any press conferences at any of the ministries and for access to government officials. Reporting critical of the government can result in press club credentials being withdrawn and media organisations losing access to news sources.

The consequence is that media outlets hesitate to ask awkward questions or report issues that they fear will upset the government, according to critics.

The Japanese media has long practised self-censorshipJake Adelstein, ex-Yomiuri Shimbun journalist

This “self-censorship” has spread to reporting on other aspects of Japanese life, such as big business owners threatening to cancel advertising contracts over negative publicity.

Things had become worse in the last 13 years, RSF said.

“Since 2012 and the rise to power of the nationalist right, journalists have complained about a climate of distrust, even hostility, towards them,” it said. “The system of ‘kisha clubs’ [reporters’ clubs], which allows only established news organisations to access press conferences and senior officials, pushes reporters towards self-censorship and constitutes blatant discrimination against freelancers and foreign reporters.”

Jake Adelstein, who in 1993 became the first non-Japanese to become a full-time journalist at the Yomiuri Shimbun, said: “The Japanese media has long practised self-censorship when it reports on anything that it fears will be controversial.”

The media’s desire to avoid antagonising anyone in government worsened noticeably in the years when Shinzo Abe was prime minister and head of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), he said.

“Abe’s administration threatened to take away the broadcasting licences of any outlets that were critical of the LDP, and he was able to convince companies to get a number of their most outspoken commentators off the air,” Adelstein told This Week in Asia.

“The media saw this and were afraid of what could happen to them,” said Adelstein, the founder of the annual Freedom of the Press Awards at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan. “They did not want to get into legal cases, and self-censorship just became the norm during Abe’s reign of terror.”

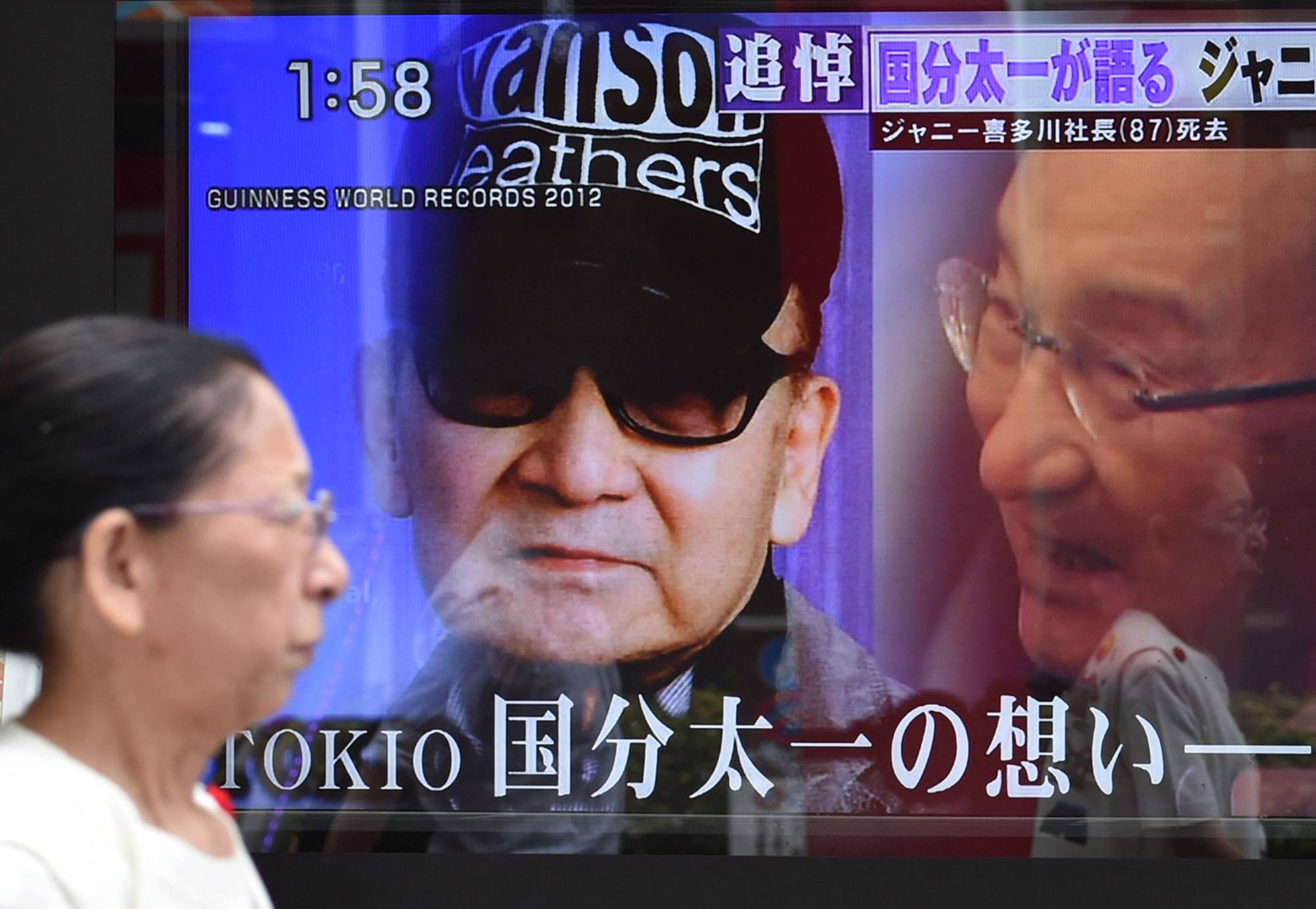

Media analysts noted it took a foreign media outlet to trigger the Johnny Kitagawa sex scandal.

In April 2023, the BBC aired a documentary accusing the late music mogul of systematically sexually abusing hundreds of young boys who hoped to become pop stars. The allegations against Kitagawa, who had been dead for four years then, were first raised by the Shukan Bunshun weekly tabloid as far back as 1999, but none of the mainstream Japanese media had reported the claims.

Even after the BBC documentary sent shock waves throughout Japan and the company he founded, Johnny’s Juniors, apologised and opened an investigation, it took national broadcaster NHK three weeks to report the matter, Adelstein said. NHK had close ties to Kitagawa’s company, with many of his musical groups appearing in the broadcaster’s programmes.

The Japanese media was also mealy-mouthed when it came to the scandal that engulfed Fuji Television Network and pop star-turned-television-celebrity Masahiro Nakai last year. Newspapers and TV channels reported that Nakai was experiencing “a woman problem”, Adelstein said, until it later emerged that he had sexually assaulted a woman who was invited to a gathering only to find herself alone with Nakai.

“The media kept referring to it as a ‘woman problem’ when in reality it was completely a Nakai problem and they were effectively covering it up,” he added.

Makoto Watanabe, a professor of communications and media at Hokkaido Bunkyo University in Eniwa, agreed that Japan’s “kisha club” system had been used to stifle a free press.

“Very few media outlets can be 100 per cent independent of either political or economic influences because of their need to get information from the government,” Watanabe said. “They cannot be excluded from that, so they instead choose to self-regulate their coverage and not write investigative or critical coverage.”

In the latter decades of the last century, media outlets were “far more independent-minded and did important work uncovering political and business scandals”.

“But that changed under Abe, who used to regularly invite senior media officials for dinner,” Watanabe said. The implications were clear about the link between reporters’ access to him or his government and how they were covered by the media, he added.

Watanabe, however, was optimistic that with the LDP politically weakened and without an unassailable leader, Japanese media freedom might improve.

“I found the recent Fuji TV case very encouraging,” he said. “It was the result of external pressure, but it has shown that even a big TV network can change.”

The retirement of the “old guard” of executives at other media outlets means a younger generation of journalists could take on more decision-making roles, according to Watanabe.

“Change happens in Japan very gradually,” he said. “But when it starts, it does gradually take hold, and I’m hopeful that we are seeing the start of that process now.”