Japan probes Chinese solar panels over hidden device fears, power disruptions

The move follows the discovery of suspicious equipment in Chinese panels by the US and Europe, potentially leading Japan to a shift towards domestic clean energy

Japan has launched an investigation into Chinese-made solar panels over fears they may contain hidden communication devices capable of disrupting the nation’s power grid – a security concern that analysts say could accelerate a shift towards domestic clean-energy technology.

The inquiry follows recent findings by authorities in the United States and Europe earlier this month, who uncovered suspicious equipment embedded in these panels not listed in the official product specifications.

The components were found in power inverters – devices that connect solar panels and wind turbines to electricity grids and allow remote access for updates. However, this equipment from at least two Chinese companies was not listed in their technical details.

Experts quoted by Reuters said the unlisted equipment provides a communication channel unknown to the operator, potentially allowing remote circumvention of security firewalls.

Allowing an external entity to remotely control inverters could disrupt power grids, damage energy infrastructure, and cause blackouts, threatening national energy security. In conflict, the ability to cut or reduce the power supply becomes a powerful weapon.

The Japanese government has started examining imported solar panels to determine whether similar undeclared equipment has been added to units sold in the country.

“For too long the Japanese government has had no real policy on imports so this is something of a wake-up call,” said Toshimitsu Shigemura, a professor of politics and international relations at Tokyo’s Waseda University.

“I am sure they will be very worried and they will be looking at these imported solar panels very closely,” he said, adding that Japanese manufacturers had lost out to cheaper Chinese imports, and if a problem was found, it could hinder Chinese sales and benefit domestic companies.

In 2024, the Photovoltaic Energy Association reported that 94.9 per cent of solar panels were imported, as noted by the Sankei newspaper – an increase of 35 percentage points from a decade ago.

An estimated 80 per cent are made in China, where the government has provided support for the industry through subsidies and generous tax breaks. Globally, Chinese companies control around 60 per cent of the solar panel market.

The discovery of the suspicious equipment has triggered accusations in Washington. Mike Rogers, a former director of the US National Security Agency, told Reuters on May 15: “We know that China believes there is value in placing at least some elements of our core infrastructure at the risk of destruction or disruption.”

They hope that widespread use of inverters will limit the West’s options to address this security issue, he added.

A spokesperson for the Chinese embassy in Washington dismissed the claims, saying they were “distorting and smearing China’s infrastructure achievements”.

Kazuto Suzuki, a professor of science and technology policy at Tokyo University and an adviser to the government, played down the risk of China being able to crash Japan’s energy grid.

“I do not know if these concerns are serious,” he told This Week in Asia. If panels could respond to an external signal to stop operations, the impact would be limited since solar accounts for only 10 per cent of the energy supply, Suzuki said.

“There might be a brief blackout, I suppose, but energy is highly decentralised, so a conventional fossil fuel plant would very quickly be able to meet demand,” he added.

“We also have to consider that if power supplies were disrupted and it was discovered that China was behind that action, it would effectively be an act of war,” he said.

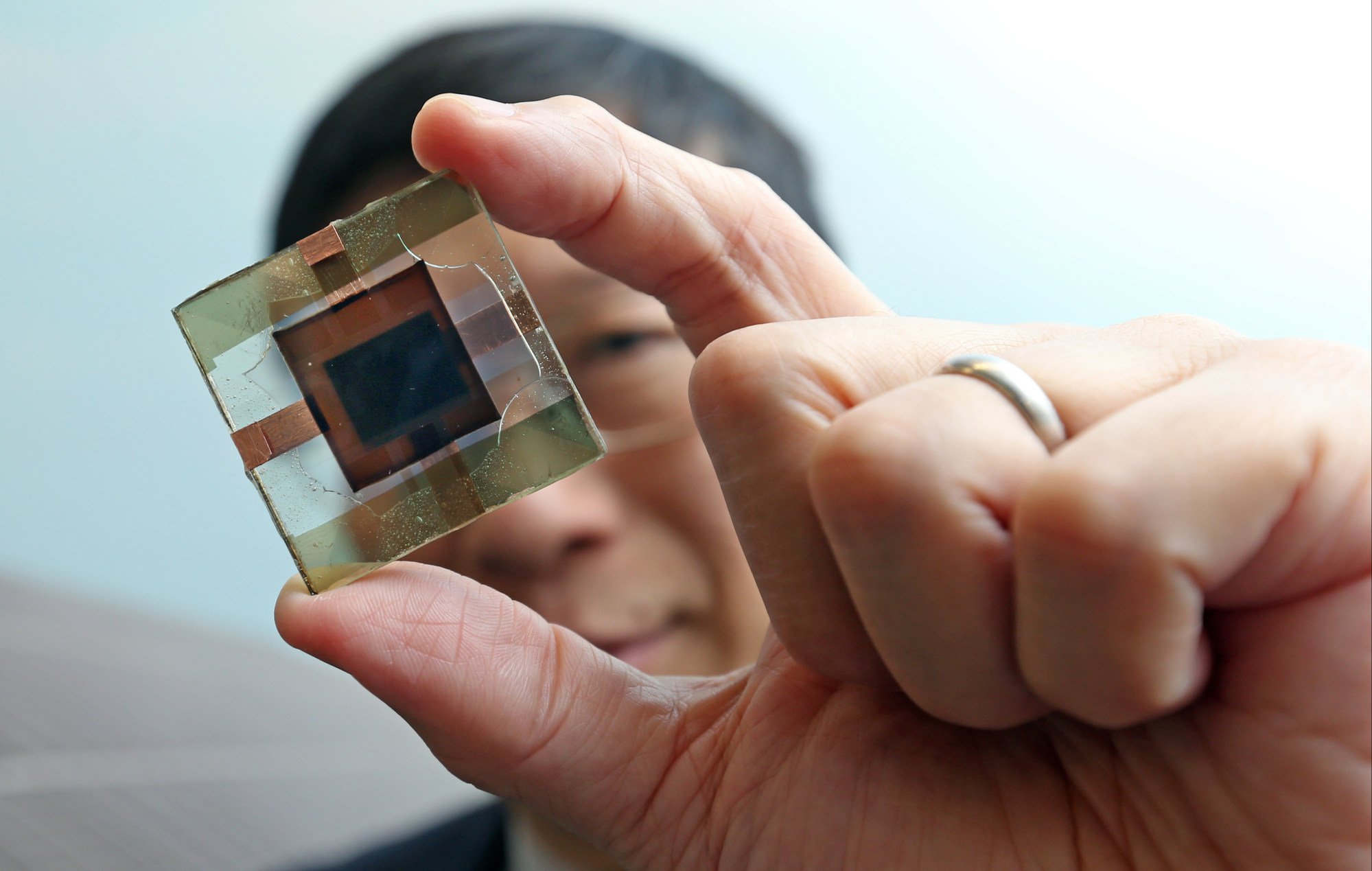

A positive consequence of Japan choosing to rely less on imported solar panels would be a greater focus on the development of next-generation perovskite solar cells.

In 2009, researchers discovered that perovskites, crystalline-oxidised minerals, have photovoltaic properties, allowing them to convert light into voltage. They are one-fifteenth the weight and one-twentieth the thickness of standard silicon solar panels.

Perovskites can also be printed on glass, meaning they can be added to the windows of high-rise buildings with glass exteriors without adding significant weight.

The Japanese government aims to reduce fossil fuel consumption and achieve carbon neutrality, with perovskite solar cells being essential to this goal. By 2040, it plans to install enough perovskite cells on buildings to generate energy equivalent to 20 nuclear power plants.