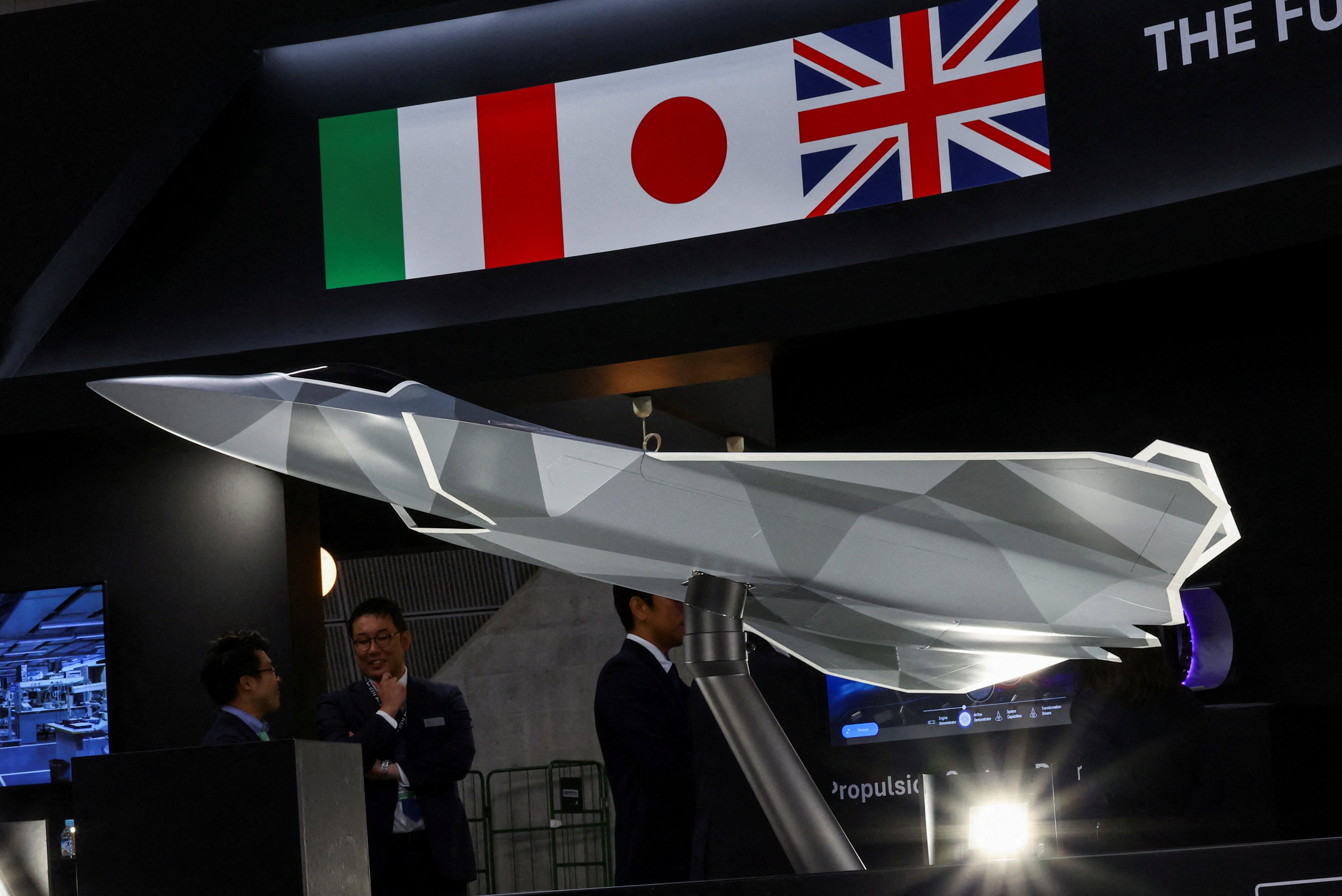

Japan grows restless for next-gen fighter jets as progress with UK, Italy stalls

Japan finds its ageing aircraft outmatched by China’s advanced stealth jets amid setbacks to the trilateral Global Combat Air Programme

At an airbase outside Tokyo, engineers inspect the ageing F-2 fighters that have patrolled the Japanese skies for decades.

But with China’s newest stealth jets roaming ever closer, and the promised future of air defence still years away, Japan is growing restless.

Its partnership with Britain and Italy to build a next-generation fighter has hit turbulence – and Tokyo may no longer be willing to wait.

The sixth-generation fighter, part of the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), is slated to enter service with all three nations by 2035. But development is reportedly lagging, with the first demonstrator flight now delayed until 2027 – a setback that has alarmed Japanese officials and defence analysts.

Unlike the UK and Italy, which can continue to rely on the Eurofighter Typhoon well into the 2040s, Japan faces a far more immediate need to modernise its fleet, according to experts.

Japan’s principal fighter force – more than 90 F-2 jets co-developed by Mitsubishi and Lockheed Martin between 1996 and 2011 – is based on the ageing F-16 platform, which first flew with the US military in the late 1970s.

Though still capable, the F-2 is seen as increasingly outmatched by China’s latest combat aircraft, such as the stealthy Chengdu J-20. Beijing is also developing the J-36, a sixth-generation fighter projected to surpass even today’s most advanced jets.

Japan lagging behind in modern air power is largely self-inflicted, analysts say.

“This is due essentially to long-term delays by Japan in choosing to replace its fighters – remarkably, the Air Self-Defence Force was still flying F-4 Phantoms just four years ago,” said Garren Mulloy, an international relations professor at Daito Bunka University and a military affairs specialist.

The Phantom, introduced by the US Navy in 1961, was retired from American service in 1996. Japan clung on to it until 2021, and South Korea only retired its last Phantoms last year.

Japan’s pivot to newer aircraft began in 2011 with the purchase of F-35 Lightning II jets – a decision Mulloy said was linked to “Operation Tomodachi”, the American military and humanitarian response to the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

The initial order expanded in 2019 under then-prime minister Shinzo Abe, who authorised the purchase of 105 more F-35s during Donald Trump’s first term as US president, bringing Japan’s total order to 147, including variants for short and vertical take-off to operate from Izumo-class carriers.

But deliveries of the F-35s are staggered over several years, leaving Japan’s air force stretched thin as it seeks to intercept Chinese incursions near the disputed Diaoyu Islands – administered by Japan as the Senkakus but claimed by China – and to monitor Russian long-range aircraft near its northern perimeter.

“There is going to be a gap because the F-2s are getting old, so Japan has a decision to make,” Mulloy said. “They can spend more on improving the F-2s and F-15s that are in service to keep them operational for longer and until the GCAP can be delivered, or they can commit to buying more F-35s from the US.”

An expanded F-35 fleet may also strengthen Japan’s hand in trade negotiations with Washington. Each aircraft costs around US$100 million, and Reuters has reported that Japan is weighing additional purchases.

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba is expected to raise the issue when he meets with Trump on the sidelines of this month’s G7 summit in Canada.

According to Japan’s Asahi Shimbun newspaper, Trump referenced America’s planned F-47 sixth-generation fighter in a May 23 call with Ishiba, signalling his willingness to broker a deal once the aircraft is operational. But Ishiba reportedly offered no firm response – wary, analysts say, of undermining the GCAP partnership with Britain and Italy.

Dr Hideaki Watanabe, chairman of the Tokyo-based Defence Technology Foundation research agency, said the divergence in the three nations’ timelines had become a sticking point.

“Japan needs this fighter sooner,” Watanabe said. “It is only after an initial flight that much of the work can be done, so this is a significant delay.”

He said Tokyo had wanted to have the new fighter jet by 2035 and was disappointed when the first demonstrator flight was delayed to 2027.

“The differences in the approaches are going to become increasingly critical, of course, but this is also a very important project for Japan, so decisions need to be taken very soon about what is going to happen if [the] GCAP is late,” Watanabe added.

The trilateral partnership to jointly develop the jet was formally announced in December 2022, merging previously separate plans for a sixth-generation platform.

Historically, Japan has sourced its combat aircraft from the United States, often securing permission to produce customised variants suited to its unique defence requirements. That latitude does not extend to the F-35, however – prompting Tokyo to pursue domestically developed alternatives.

Japan’s air defence posture, built around extended maritime operations, demands long-range fighters with heavy payloads. The F-35, with its single engine and limited range, falls short in this regard. The GCAP, by contrast, promises nearly double the weapons capacity and is designed to operate as a “mother ship” for autonomous drones providing strike and surveillance capabilities.

Mulloy rejected suggestions that the UK’s Ministry of Defence had been intentionally “dragging its feet” on the GCAP project. Instead, he pointed to Nato’s preoccupation with Ukraine and a broader strategic realignment under Trump.

“Nato has been extremely focused on a defence augmentation shopping list that reflects its relationship with Ukraine during the war as well as the present US administration,” he said.

All projects – even if they are purely national – come up against issues involving delays and cost overrunsGarren Mulloy, defence analyst

Japan, he added, had largely remained insulated from the fallout of the Ukraine conflict and European defence recalibrations.

“All projects – even if they are purely national – come up against issues involving delays and cost overruns if you are dealing with this sort of very complicated technology,” Mulloy said, adding that Japan would make the necessary decisions to address delivery delays.