Inside the minds of Singapore’s opposition members – why do they keep coming back?

SDP’s Chee Soon Juan and Paul Tambyah, WP’s Yee Jenn Jong and SDA’s Desmond Lim explain why politics matter to them despite the hurdles

As the May 3 election results trickled in, Singapore Democratic Party (SDP) chief Chee Soon Juan found himself again on the wrong side of the electoral ledger – a familiar outcome in a three-decade political journey defined as much by its longevity as its unending losing streak.

His fight in the single-seat constituency of Sembawang West, with 46.81 per cent of the vote against a ruling-party candidate, was his best performance in the polls since 1997 and the third-closest of the night, coming after the Workers’ Party’s (WP) narrow defeat in the multi-seat ward in Tampines, with 1 percentage point separating the WP and SDP.

In a post-election interview with This Week in Asia, Chee said the result offered some comfort, though his broader vision of a democratic Singapore was still far from realised – possibly not in his lifetime.

A viral video filmed from a distance in a stadium for the SDP’s watch party had gained Chee much post-election sympathy as he cut a forlorn figure while wiping away tears. He clarified he was merely weary that night and had removed his glasses to rub his eyes – a moment of fatigue rather than any dramatic display.

“Change comes when you stand on the shoulders of those who come before you,” he said. “Change may come only when you have gone from the scene. But whatever you do, you lay the groundwork for the next generation.”

Chee is one of the many opposition figures in Singapore who have failed to make it past the ballot box despite multiple attempts but they are not about to give up.

In This Week in Asia’s interviews with four opposition politicians from three parties, all spoke of a shared conviction: that electoral success was just one milestone in a longer fight for democracy in a one-party dominant state.

In this year’s election, 10 opposition parties contested – part of a long and crowded lineage of political challengers in Singapore’s history. Since independence in 1965, 40 opposition parties have come and gone, many of them fading without ever securing a seat.

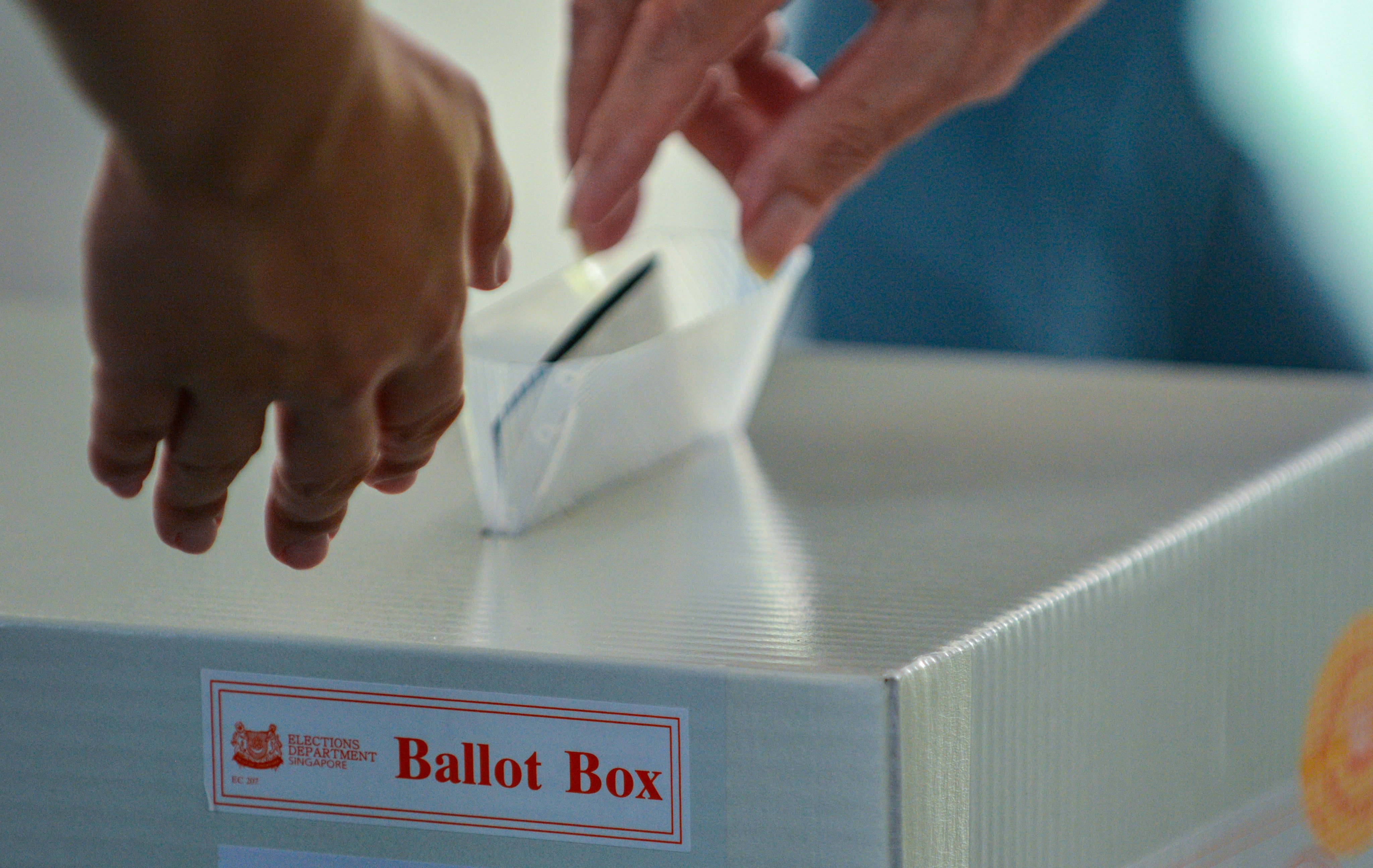

But others continue to show up and contest, offering voters a chance to have a choice at the ballot box – even at constituencies where the odds are heavily stacked against them.

“It gives voters a choice. If they don’t stand, then there will be no election. They keep coming back because they genuinely believe in performing a public service,” said Mustafa Izzuddin, a senior analyst at Solaris Strategies Singapore.

A 2021 study by the Institute of Policy Studies, which surveyed 2,000 Singaporeans, found that most respondents believed general elections were fair, offered genuine choices, and gave them some say in government policy.

But Chong Ja Ian, a political scientist from the National University of Singapore (NUS), suggested that some features of Singapore’s electoral process, such as the short campaign timeline and mainstream media representation, put opposition parties at a disadvantage.

“The electoral process does not have any stuffing of the ballot boxes or irregularities like that. However, there are clear differences in the resources available to the various political parties,” he said.

“Members of the public and the opposition parties often ask why the electoral boundary determination process is conducted under the prime minister’s office and why the rationale for each case of redistricting is not easily available to the public.”

In the latest election, most opposition parties – besides the incumbent’s main adversary the WP – recorded a substantial drop in vote share, which some analysts had attributed to a “flight to familiarity”, greater discernment about opposition quality and the ruling party’s strong campaign message.

The People’s Action Party (PAP) won 87 out of 97 parliamentary seats, and secured a 4 percentage-point increase from the previous 2020 general election, while the opposition maintained the constitutional minimum of 12 seats, including 10 elected ones.

During the nine-day sprint to the polls, Prime Minister Lawrence Wong drilled into the electorate the need to give him a strong mandate and a full-strength cabinet to weather the economic headwinds unleashed by the intensifying trade war between the United States and China.

“It’s a clear signal of trust, stability and confidence in your government. Singaporeans, too, can draw strength from this and look ahead to our future with confidence,” he said at a postmortem briefing on May 4.

The resounding victory was widely seen as a vote of confidence in Wong’s leadership amid rising costs of living – defying historical precedent of a dip in support during leadership transitions. It was his first general election as prime minister and secretary general of the PAP.

The outcome was also a result of a well-executed strategy by the PAP, having done extensive ground work in the lead-up to the poll, one political observer said.

“They got it right where the opposition got it wrong. It’s also important to look at where the PAP has got it right, which includes the focus on a very effective ground campaign,” Mustafa said.

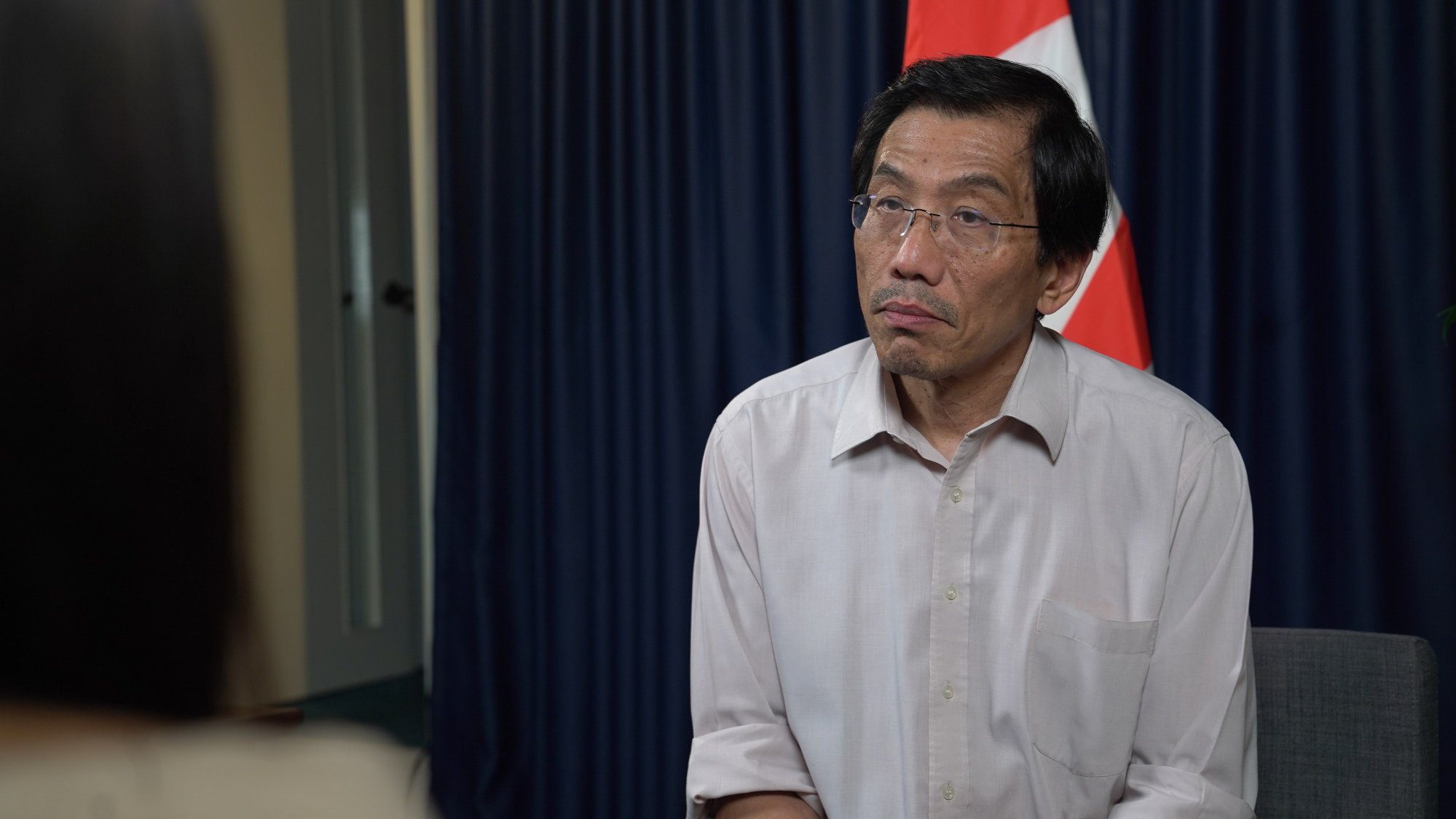

SDP chairman Paul Tambyah noted the PAP had from the beginning called it a “tariff election”. “So, coincidentally, the Australian, Canadian elections have been around the same time and you got the same results – a vote for the status quo. Because with such an unpredictable situation in the US, you really, really needed some kind of stability. And people were not willing to take a risk,” he told This Week in Asia.

Amid the sobering reality check for the opposition, some members of the camp also point to electoral boundaries being redrawn and uneven resources as formidable challenges against making any headway.

“The way the PAP runs elections is they shift the goalposts … they do all kinds of things and then when they win, they say they have a landslide,” Tambyah added.

The Electoral Boundaries Review Committee introduced major changes to the city state’s electoral map, leaving only five multi-seat and four single-seat constituencies unchanged from the last 2020 election cycle.

The committee cited population shifts and new housing developments in divisions such as Sembawang and Tampines, as reasons behind redrawn boundaries.

The Bukit Panjang ward, where Tambyah contested, was among the few that were left untouched. The infectious diseases doctor said he sensed early in the campaign that the ruling party already had Bukit Panjang “in the bag” – a feeling reinforced during walkabouts where residents frequently asked if he could continue a S$1 (77 US cents) egg deal programme if elected.

The Bukit Panjang Dollar Deal initiative, launched in 2024, offered residents subsidised eggs, meals or vegetables each month for S$1. It was backed by S$500,000 in funding from the North West Support Grant, as part of a S$9.5 million grant launched by the North West Community Development Council, one of five CDCs operating under the People’s Association (PA), a statutory board under the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth.

The PAP rival in the recent election, who was also the incumbent for the ward, was the adviser to Bukit Panjang grass-roots organisations, which had contributed to hosting the monthly deal.

Tambyah, 60, ultimately lost the single-seat ward to his PAP opponent by about 22 percentage points in a rematch, a significant drop from a margin of 7 percentage points in the previous 2020 general election.

“I was asked what my target was and I said it was 49 per cent and I wasn’t kidding, because I realised that it was a hugely uphill battle and if I could improve from 46 per cent [in 2020], that would be an achievement,” he said.

But Tambyah sees the results as a product of a system that favours the incumbent. “So when you have that kind of system, to blame the voter or blame the party is blaming the forest for the trees,” he said.

Chong from NUS said many voters tended to associate state-provided benefits with prospective PAP candidates in the PA grass-roots capacities, which blurred the line between party and state for those who lost sight of the details.

“Some voters may fear that benefits may go away if the PAP is not returned to office, even though some of these benefits are state programmes paid for through public monies.”

‘They don’t get any limelight’

It may seem odd that Singapore’s political parties contest in an election without ambitions of clinching a seat, much less forming the government, but this is very much par for the course, according to political observers.

Instead, for many opposition candidates, the election period gave them some much-needed airtime to publicise their views, Mustafa noted.

“Because otherwise, apart from the election, they don’t really get any kind of limelight … During the campaign all eyes are on candidates, so you have an opportunity to be featured,” he said.

This was the first general election in Singapore where major mainstream media outlets – Mediacorp and the Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) – are government-funded. The SPH’s media business was restructured into a not-for-profit entity in 2021 and is now publicly funded through government grants.

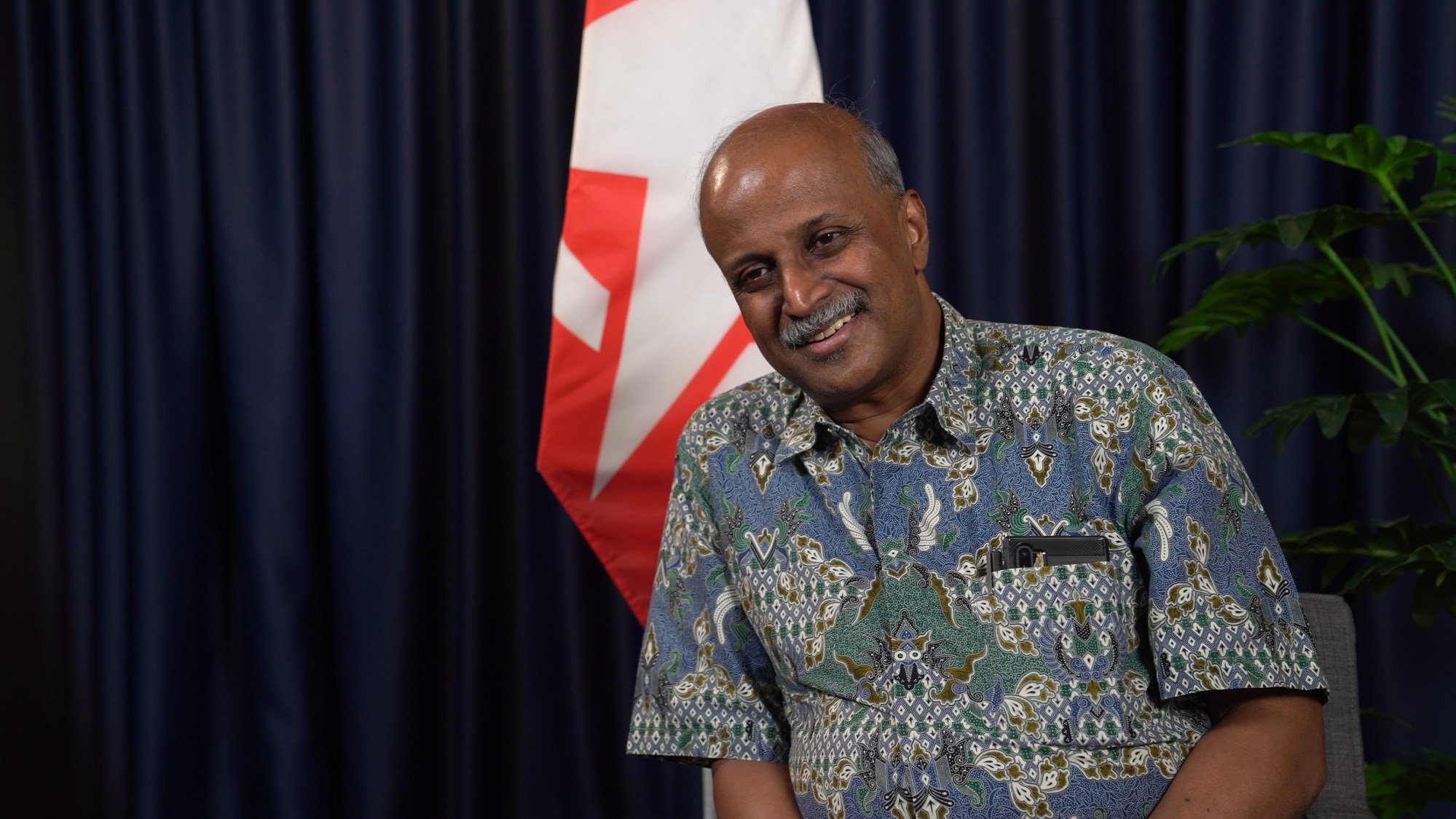

For Desmond Lim, chief of the Singapore Democratic Alliance (SDA), victory in the conventional sense may remain elusive as an opposition party – yet he believes that contesting elections is still a crucial part of a broader strategy.

Responding to the label of being a “mosquito party” – a term coined by pundits to dismiss small, seemingly irrelevant opposition who may dilute the vote share – Lim said the act of standing for elections helped prevent walkovers and forced the ruling party to commit resources and attention across all contested wards, rather than concentrating efforts only in battleground constituencies.

“If you think you’re better, then please come forward to contest,” Lim argued, saying it was “disrespectful” to call smaller opposition parties “mosquitoes”.

The SDA bucked the broader downward trend among opposition parties, improving its vote share by more than 8 percentage points to 32.34 per cent in Pasir Ris-Changi, the only constituency it contested, compared with 23.67 per cent when it contested in Pasir Ris-Punggol in 2020.

At the time of its 2001 formation, SDA was a coalition of several small parties.

The alliance was previously led by Chiam See Tong, an iconic opposition figure in Singapore’s political landscape and the founder of SDP, who had served as a unifying factor in the SDA.

Chiam’s withdrawal of his Singapore People’s Party from the SDA in 2011 ahead of the election that year marked a turning point for the coalition.

But Lim never expected to take over the helm, saying he was forced into the position by circumstance, even if it came at the expense of his private life. “I am a good grass-roots leader, a doer, an organiser. But then the situation developed such that I had no choice [but to lead the party],” he said.

“This election, I told my son also, I said: I’m going to contest, because last time my son was young, now he’s 13 years old. I [said to him]: whatever you read in social media, don’t go and rebuke or challenge them.”

‘10 opposition MPs is enough’

Echoing the David-versus-Goliath battle Lim had painted for his party and the opposition as a whole, SDP’s Tambyah said: “If we get an upset, that’ll be fantastic but the structural odds against us are so steep that it is really, really challenging.”

He refuted the PAP’s reasoning that a strong opposition would weaken the government, and insisted that having strong teams challenging the incumbent would instead strengthen the latter, ultimately to the benefit of the country.

While upsets are few and far between, when a ward falls into opposition hands, it does push the incumbent to change policies, according to Yee Jenn Jong, who led the WP team in the East Coast multi-seat constituency.

This year’s election marked his fourth failed bid for a parliamentary seat, though his near-miss in the 2011 race clinched him a seat as a non-constituency member of parliament.

“I’m very sure that it’s the shock electoral loss in 2011, and to prevent further losses, they are forced to change,” he said.

The 2011 general election marked a historic breakthrough for Singapore’s opposition, as the WP became the first to win a multi-seat constituency since the system was introduced in 1988.

The party retained its Hougang single-seat ward and clinched the five-member Aljunied constituency, unseating a PAP team led by then foreign minister George Yeo – a result widely seen as a watershed moment.

The WP continued to make electoral gains in 2020, when it captured the newly created Sengkang multi-seat constituency.

In response, then prime minister Lee Hsien Loong appointed WP chief Pritam Singh as Singapore’s first official Leader of the Opposition – a move that acknowledged a growing public appetite for more diverse political representation.

According to Chong, the WP has managed to close the quality gap with the incumbent due to better resources and internal manpower, though this is not the case for smaller parties like Progress Singapore Party, which is led by former PAP MP Tan Cheng Bock, and the SDP.

“The other political parties other than the PAP do not have the same capabilities. The SDP has a clear narrative and support base, but seems to have trouble building on them,” he said.

While PSP might have experience and some resources, it failed to convince voters that the party was more than Tan, Chong added.

“Apart from branding, the WP has more consciously tried to represent the hopes and aspirations of Singaporeans,” Chong said.

Although his party has made electoral headway, the recent election is the last outing for Yee as the 60-year-old wants to make way for younger blood to take on the long-haul responsibility of opposition work.

In a speech after the results of East Coast multi-seat constituency were announced, Yee said he was proud of the quality of his teammates, which exceeded his expectations when he first joined politics over a decade ago. “Saying goodbye is always very difficult but at some point in time, goodbyes have to be said,” he said in an address to supporters, as he held back tears.

Reflecting on his extensive political career in an interview with This Week in Asia, he said: “That five years from one election to the next is always the loneliest and the most difficult when you have lost, so you need to continue walking the ground and your volunteers will dwindle because everybody gets busy.”

However, he recognises that voters remain deeply cautious – having expressed to him concerns that a vote for the opposition could disrupt the stability that the ruling party promises or affect how their neighbourhoods would be run.

“I have people outright telling me in this campaign that ‘10 MPs is enough, how many more alternative voices do you need?’” he said. “It’s really hard to undo more than 60 years of the PAP being in power.”

But even as he bows out, Yee remains hopeful that the WP will continue to attract more quality candidates, pointing out that its latest slate of newcomers included a senior counsel, an ex-diplomat and a Harvard graduate.

“It has improved, thankfully, in the sense that people have seen the Workers’ Party has run town councils well, has performed responsibly in parliament, so then more people are willing to join,” he said.

The WP solidified its position as Singapore’s strongest opposition force, having retained its 10 elected seats across Aljunied multi-seat constituency, Sengkang multi-seat constituency and Hougang single-seat ward, and clinching an additional two non-constituency members of parliament seats.

Its vote share was 50.04 per cent in eight constituencies, a slight drop from the 50.49 per cent across six constituencies in 2020.

Speaking to reporters after polling day, Singh said the party had done “very commendably” despite a vote swing to the ruling PAP.

In 2019, Singh said the party’s medium-term goal was to contest and win one-third of the seats in parliament. But in this election, the party fielded 26 candidates, fewer candidates than needed to meet that target.

Yee said the WP was still not at the point where it was prepared to take over the government.

“I believe that one day we can form the government, but if you tell people now that we are forming the government, people will laugh. We can’t even contest one-third of the seats. That’s the reality, it’s so difficult to get talent,” he said.

‘People thought I was insane’

Even at 62, Chee showed little sign of retreat, appearing in a social media video less than a week after the results, where he announced that “plans are afoot to press ahead”.

The veteran opposition figure told This Week in Asia he had no plans to step aside just yet – unless his body indicated it was time.

Reflecting on whether his past as an activist continued to shadow his public image, he acknowledged the impact of “poisonous rhetoric” against him.

“People literally thought that I was insane because Lee Kuan Yew at some point said that I was a near-psychopath,” he said.

Chee’s decades-long political journey has been marred by controversy. Formerly a psychology lecturer at NUS, he was dismissed from his post after a dispute with the university over the use of research funds – a move he has long contended was politically motivated.

He was once again the centre of public scrutiny after publicly confronting then prime minister Goh Chok Tong during a walkabout, an act that led to defamation lawsuits and a string of legal troubles that left him bankrupt in 2006.

Over the years, Chee has been jailed multiple times, including for speaking at public rallies without a permit, and once staged a hunger strike to protest against his dismissal.

But the advent of social media had tipped the scales slightly in his favour, Chee said, adding it broke the trend of “one-way information”. “I’ve had people come up to say, hey, you look very normal. You sound very normal … And people are beginning to see that this guy, at least he doesn’t talk nonsense.”

Still, Chee remained clear-eyed about the limits of his reach.

“Let’s not be under any illusion that with the situation here in Singapore, that things are going to happen [overnight],” he warned, stressing however that his party’s mission was to pave the way if and when changes were to happen.

“As long as it keeps ticking, you keep going until one day you find that physically, mentally, you cannot go on. And you’ll know it and you don’t want to outstay your welcome,” he said.

“And hopefully you’ve left the place a little better than when you first came into.”

Additional reporting by Jean Iau