Indonesia’s green groups welcome move to axe mining permits in Raja Ampat

Prabowo cancels four mining permits in Raja Ampat, but concerns remain over nickel exploitation on Gag Island and other small islands in Indonesia

Indonesia’s green groups and Papuan residents have welcomed President Prabowo Subianto’s decision to revoke almost all nickel-mining permits in the country’s biodiversity gem of the Raja Ampat Islands, but urged authorities to protect other small and outlying areas from damage brought by such activities.

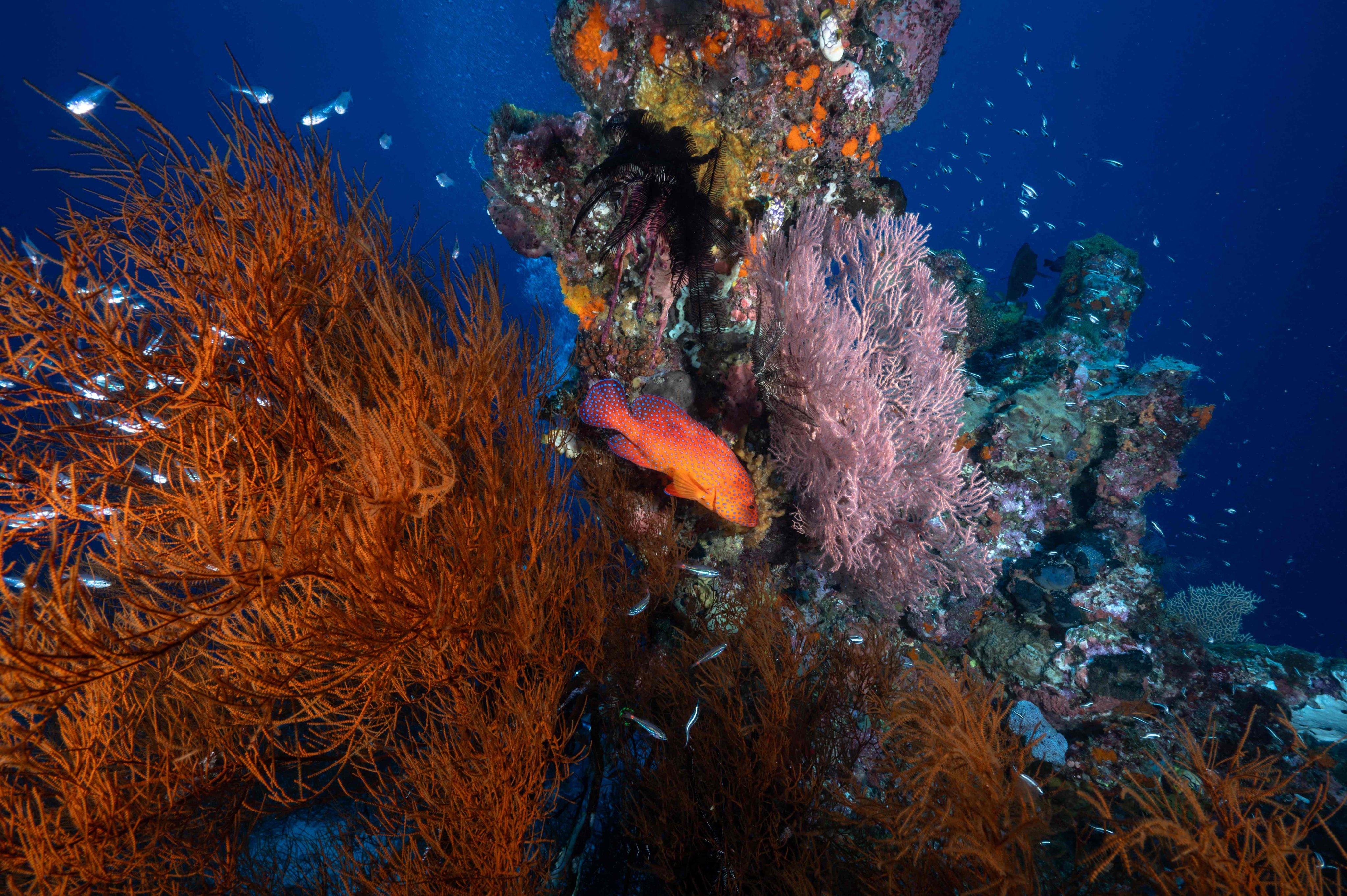

Raja Ampat, an archipelagic region in Southwest Papua, has been dubbed the “last paradise on Earth” due to its extremely rich terrestrial and marine biodiversity, which includes 540 species of coral and more than 1,500 species of fish.

The postcard-perfect archipelago, comprising more than 610 islands, is popular among divers, including those who can pay extra for luxury yachts and eco-friendly lodges.

It was no surprise that Indonesians were up in arms to condemn nickel mining in the region, after the issue was exposed by Greenpeace Indonesia and four young Papuans who staged a protest during the Indonesia Critical Minerals expo in Jakarta on June 3.

According to Greenpeace, nickel mining has already led to the destruction of “over 500 hectares of forest and specialised native vegetation” in three islands within Raja Ampat: Gag Island, Kawe Island and Manuran Island.

“Extensive documentation shows soil runoff causing turbidity and sedimentation in coastal waters – a direct threat to Raja Ampat’s delicate coral reefs and marine ecosystems – as a result of deforestation and excavation,” Greenpeace claimed in a statement on June 3.

Other small islands in Raja Ampat, such as Batang Pele and Manyaifun, were also “under imminent threat” from nickel mining, and these two islands were located about 30km from Piaynemo, the iconic karst island formation depicted on Indonesia’s 100,000-rupiah banknote.

The islands are categorised as small, on which mining is forbidden, per Indonesia’s 2014 law on coastal areas and small islands.

Online users have taken to the hashtag “Save Raja Ampat” on social media platform X to voice their displeasure at the perceived environmental destruction.

The furore forced Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources Bahlil Lahadalia to temporarily halt the permit of Gag Nikel, the nickel miner in Gag Island on June 5, but the measure was not enough to quell public outrage.

On Tuesday, Prabowo permanently revoked four mining permits in Raja Ampat Islands, except that of Gag Nikel.

“Gag Nikel is the only one that has a work plan and budget this year. Its location is about 42km from the Piaynemo Geopark and is actually closer to North Maluku. Of the total 260 hectares [642 acres] of land used, 54 hectares have been [rehabilitated] and returned to the state,” Bahlil said.

Gag Nikel’s operations were still suspended despite the government maintaining its permit, Dadan Kusdiana, secretary general at the ministry of energy and mineral resources, told state news agency Antara on Tuesday.

According to Mining Advocacy Network (Jatam), the company earned the permit in 2017, which covers mining concessions of 13,136 hectares, twice the size of Gag Island’s 6,500 hectares land. More than 6,000 hectares of land in Gag have been declared a protected forest.

Minister of Environment Hanif Faisol Nurofiq on Sunday told reporters that Gag Nikel’s mining activities “relatively meet environmental management principles”.

“The level of pollution [on Gag Island] that is visible to the eye is almost not too serious,” he said.

No to mining

The permit revocation was welcomed by green groups and Papuan residents, though concerns remain over nickel exploitation on Gag Island.

“The cancellation of these four mining permits is a glimmer of good news and an important first step towards full and permanent protection for all of Raja Ampat from the nickel industry,” Kiki Taufik, head of Greenpeace Indonesia’s forest campaign, said in a statement on Tuesday.

“We continue to demand full and permanent protection for all of Raja Ampat, including cancellation of all mining licences, active and non-active, including that of PT Gag Nikel.”

Ronisel Mambrasar, a resident of Manyaifun, thanked the government for revoking the permits.

“Mining on small islands in Raja Ampat is wrong, it goes against the law,” Ronisel told This Week in Asia. “The president has made a wiser decision. That is a good step, so that this does not prolong the controversy for the people of Raja Ampat.”

Ronisel, who is also a member of Raja Ampat Nature Protection Alliance, said some of the trees in his village had been cut to make ways for roads and lodgings for mining workers, but that the legal operation there had not yet commenced.

Ronisel added that the coral reefs and fish habitats in the waters around Manyaifun and Batang Pele remained in good condition, which was essential to most of the islands’ 744 residents who work as fishermen.

“I hope the government will pay more attention to Raja Ampat communities by opening up job opportunities for them, so that they will not be dependent on companies that damage the environment,” Ronisel said.

According to Jatam, before the mining permits in Raja Ampat were cancelled, 195 approvals had been issued allowing companies to mine on 35 small islands across the country, with a total concession area of 351,933 hectares.

“What is needed next is legal protection for Raja Ampat and other small islands, so that mining companies do not enter Raja Ampat and small islands that are ecologically important to the environment,” said Melky Nahar, national coordinator at Jatam.

He pointed out that both the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court had ruled that mining activities were forbidden on small and outlying islands, but “the rulings have not been obeyed on the ground”.

Melky also urged the government to reconsider its drive to boost the domestic nickel-refining industry, which had increased the demand for coal in Sumatra and Kalimantan islands.

“The government claims [the nickel ore export ban] policy is to support energy transition in the transport sector. More than 85 per cent of our nickel is not made for [electric vehicle batteries], but for stainless steel. The huge energy demand has triggered increased coal mining exploitation in Kalimantan, so this is clearly nonsense,” he said.