Indonesia and Malaysia set model for dispute resolution with Ambalat pact

The neighbours will jointly develop Ambalat despite their decades-long disagreement over ownership of the resource-rich sea block

The decision by Indonesia and Malaysia to jointly develop the resource-rich Ambalat sea block signals a pragmatic step towards defusing a decades-old territorial stand-off, even as legal uncertainties over sovereignty remain unresolved.

The agreement was announced last week during Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s visit to Indonesia, where he met with Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto to discuss maritime and land border disputes, investment, and regional conflicts, among others.

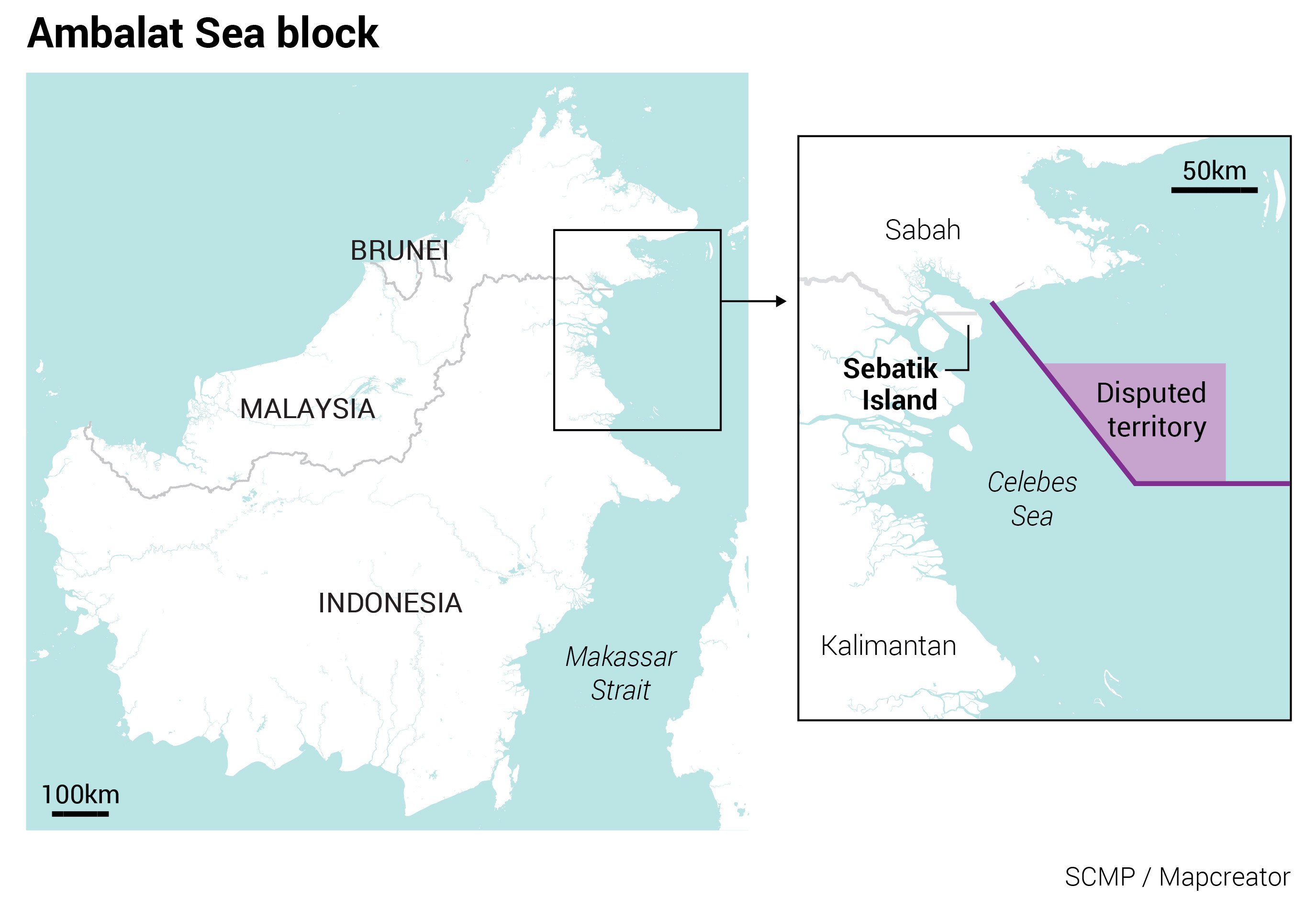

Prabowo said he and Anwar had agreed to “seek mutually beneficial solutions” over Ambalat. Located east of Borneo, Ambalat is believed to hold vast oil and gas reserves.

“While we resolve the legal aspects, we will begin economic cooperation under what we call joint development,” Prabowo said in the presidential palace in Jakarta on Friday.

“Whatever potential is found in these waters, we will exploit it together fairly,” he added.

Anwar said there was “no obstacle” for Indonesia and Malaysia to start their economic cooperation in Ambalat, including by setting up “a joint development authority” to manage the block.

“If we wait for a legal settlement, it could take up to two decades. It is better for us to use the available time to obtain real results, for the benefit of the people in the border area,” Anwar said.

Both leaders are scheduled to meet again in July, which Prabowo hopes will offer “momentum for the technical resolution of several issues”.

Pros and cons

The plan for a joint development in Ambalat reflected recent examples of how members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) were properly addressing territorial and sovereignty disputes within the region, said Collin Koh, senior fellow at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies in Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

“Over the decades Asean member states have settled those land and maritime disputes in amicable ways, either via a political agreement or by resorting to international legal recourse, such as the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea and the International Court of Justice, but in the recent decade or so there appears to be a slowdown on that,” Koh said.

“Given the current geopolitical upheavals and the ensuing uncertainties, the Ambalat pact is a way of instilling more assurances to not only external parties but also domestic audiences.”

Koh pointed to the ongoing Cambodia-Thailand border spat, which has led to the suspension of Thai Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra on Tuesday. Tensions between the neighbours escalated in recent weeks, including an armed confrontation on May 28, which killed a Cambodian soldier.

Aristyo Darmawan, an expert on international law at the University of Indonesia, said the agreement was a “positive” development in the decades-long Ambalat dispute, underlining Prabowo’s “good neighbour” policy.

Prabowo has repeatedly said his foreign policy follows the proverb that “a thousand friends are too few, one enemy is too many”.

Aristyo said: “This also shows that there is a shift in our policy in Ambalat. In the era of [former Indonesian president] Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, the narrative surrounding Ambalat was that it is ours and Malaysia unilaterally took it.

“Now, under Prabowo, the narrative is that we have overlapping maritime boundaries with Malaysia in Ambalat, and that it has not been resolved.”

According to Aristyo, the joint development plan over Ambalat abides by Article 83 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos), which says “states may enter into provisional arrangements to manage the area” while they seek final delimitation in the disputed area.

The deal with Malaysia is different from a similar agreement between Indonesia and China for joint development of maritime resources in waters near Natuna Island in November, according to analysts. The latter agreement has sparked controversy as Indonesia was perceived to have acknowledged Beijing’s nine-dash lines claim in the South China Sea.

“That joint development plan [with Beijing] was outside international law,” Aristyo said.

However, both agreements contained the same “underlying logic”, in which Prabowo implemented “a pragmatic approach to border disputes to generate economic benefits for Indonesia, as he aims to reach an eight per cent economic growth”, Aristyo said.

In Malaysia, Sabah’s Deputy Chief Minister Jeffrey Kitingan said he was “disappointed” with the joint development plan in Ambalat, which is located near Sabah’s maritime borders.

“Ambalat has always been considered part of Sabah’s territorial waters,” Kitingan said on Tuesday, according to a Malay Mail report.

“If this decision was truly made without consulting Sabah, then it is not good. It’s another way of bypassing Sabah’s rights. And we need an explanation.”

Kitingan, who is also a lawmaker, said that he would seek “formal clarification” and raise the matter in the Malaysian parliament.

Legal issues

Overlapping claims between Indonesia and Malaysia over the 15,000 sq km Ambalat sea block are widely believed to have begun in 1967. When Malaysia unilaterally drew a map in 1979 showing its territorial sea and continental shelf border, which included Ambalat in the Celebes Sea, tensions over the dispute between both sides reached a peak.

Indonesia justifies its claims by pointing to an Unclos 1982 rule, which states archipelagic countries such as itself calculate their baselines for maritime delimitation from their outermost island.

It has accused Kuala Lumpur of inaccurately calculating its basepoint, saying Malaysia is considered a coastal state, not an archipelago, so it can only use regular baselines to define its territorial boundaries.

This difference in interpretation has been hindering efforts to resolve the Ambalat issue all these years, according to Fauzan, an international relations lecturer at Universitas Pembangunan Nasional in Yogyakarta, who specialises in border management and security.

In 2002, the International Court of Justice awarded the islands of Sipadan and Ligitan, also in the Celebes Sea, to Malaysia, but it did not establish delimitations in the surrounding waters.

The ICJ case might have shaped Indonesia’s position over Ambalat, Fauzan said.

“Our legal standing is strong enough to maintain our claim of Ambalat. But we are maybe still traumatised from losing to Malaysia in the international court.”