India’s UK trade pact seen as fuelling momentum for bigger deals with US and EU

Experts say the agreement signals New Delhi’s growing leverage in trade and supply chain talks

India’s landmark trade pact with Britain – three years in the making – could pave the way for similar agreements with the United States and European Union, analysts said, as New Delhi looks to cement its role in reconfigured global supply chains.

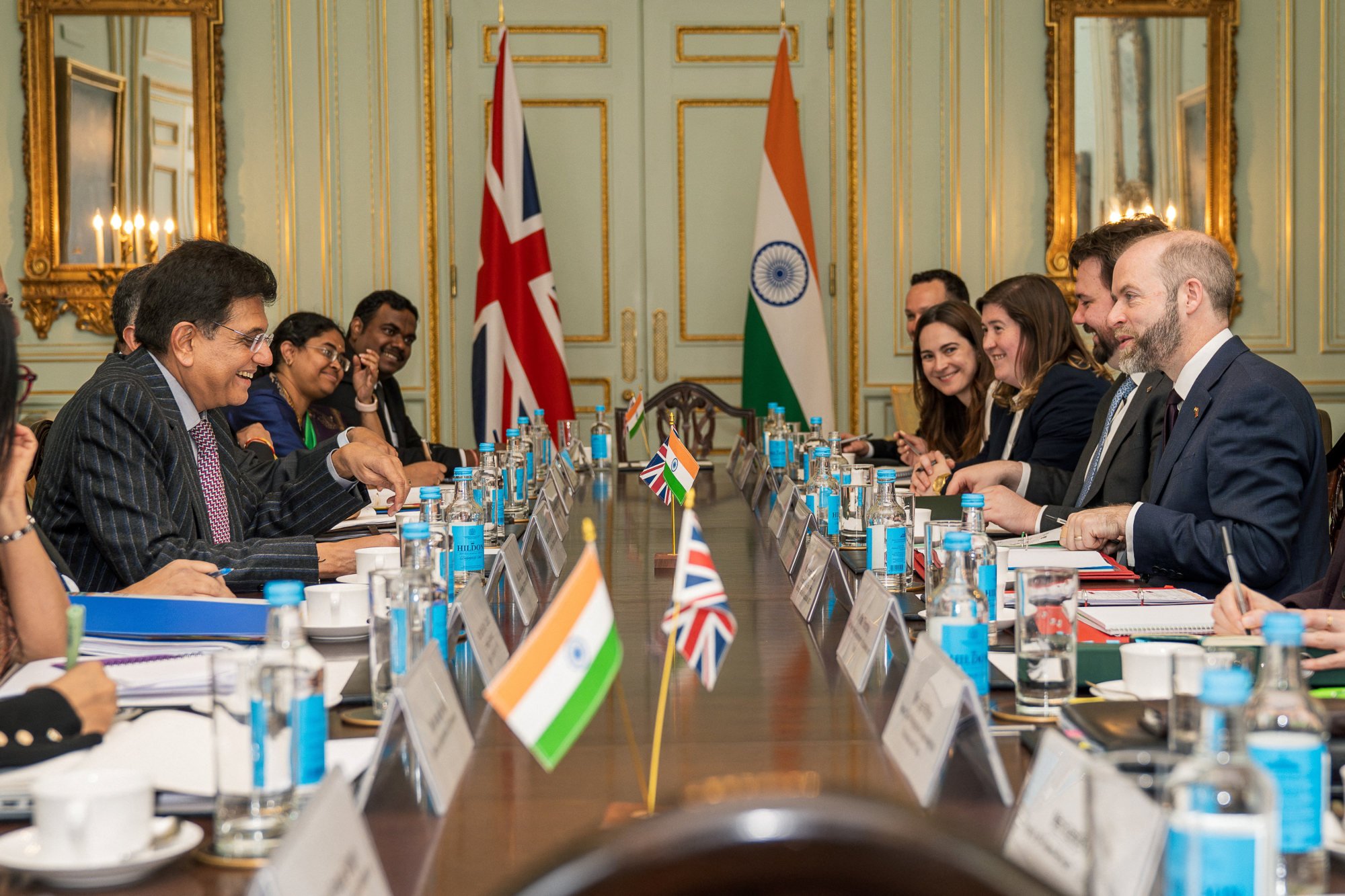

Announced on Tuesday, the free-trade agreement aims to reduce tariffs and ease market access between the world’s fifth- and sixth-largest economies, with both sides touting its potential to create jobs, boost investment and spur innovation.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi described the deal as “ambitious and mutually beneficial”, while British Prime Minister Keir Starmer hailed it as a significant step in a “new era for trade” between the two nations.

Though final legal touches are still pending, UK officials say the deal marks Britain’s most significant trade achievement since it left the EU in 2020.

The agreement is expected to boost investment, generate jobs and support technology transfer between the two countries, said Pratik Dattani, founder of London-based think tank Bridge India.

He added that the intensifying US-China trade war likely gave fresh momentum to the talks, as more countries seek to diversify their markets and reduce reliance on the world’s two largest economies.

US President Donald Trump announced steep new import tariffs on several countries last month, but Washington later suspended the levies until early July to allow for negotiations – with China notably excluded from the reprieve.

Given the economic strain from Trump’s tariffs and the challenges of the post-Brexit landscape, it was imperative for the UK to secure new sources of growth, Dattani said.

The agreement is set to increase bilateral trade by £25.5 billion (US$34.13 billion) annually by 2040, according to British government estimates. Trade between the two nations reached £42.6 billion last year, with India ranking as the UK’s 11th-largest trading partner.

India – known for having some of the world’s steepest import tariffs – will lower duties on 90 per cent of British goods under the deal, including liquor, machinery and medical devices. Of these, 85 per cent are set to become tariff-free within a decade.

Tariffs on whisky and gin, for instance, will be slashed from 150 per cent to 75 per cent, before dropping to 40 per cent by year 10. Car tariffs will fall from more than 100 per cent to just 10 per cent.

In return, Britain will eliminate tariffs on nearly all Indian exports, particularly benefiting labour-intensive sectors such as textiles, footwear, pharmaceuticals, marine goods and leather. India’s Trade Ministry said 99 per cent of Indian exports would be exempt from import duty once the agreement takes effect.

New Delhi had pushed for expanded visa access to improve mobility for Indian workers, and while the final agreement fell short of sweeping immigration changes, it includes targeted provisions to facilitate the temporary movement of skilled professionals. These apply to categories such as intra-corporate transferees, business visitors and independent service suppliers, and are expected to benefit sectors like information technology and healthcare.

T.S. Vishwanath, a trade expert based in New Delhi, said those changes would likely increase India’s services exports by easing the movement of skilled workers, even under the UK’s existing immigration rules.

He added that the provisions could also serve as a model for a bilateral trade deal currently being negotiated between India and the United States.

Washington has said that India, South Korea and Japan are likely to be among the first few countries with which it will sign trade agreements following Trump’s tariff threats.

The agreement is also expected to strengthen New Delhi’s trade negotiations with the European Union and could help revive stalled talks with Canada, Vishwanath said.

Trade discussions with Ottawa had broken down in recent months amid diplomatic tensions, but the election of Mark Carney as Canada’s new prime minister may open the door to renewed engagement.

India is also likely to sign a free-trade agreement with New Zealand soon, Vishwanath said.

“What [India is] looking at is far more integration of value chains on services and manufacturing,” he added.

Boost to UK’s Labour Party

In Britain, the deal is also seen as a political win for the Labour Party, which took office last year.

“It showcases Labour’s global economic vision and ability to secure major deals post-Brexit,” said Chris Blackburn, a London-based international relations analyst. “It may help rebuild trust with business and immigrant communities.”

He added that the agreement could enhance India’s reputation as a credible trade partner, giving momentum to talks with the US by showing that New Delhi is serious about liberalisation.

Priyajit Debsarkar, a London-based Indian author, said the timing of the agreement was also noteworthy given the escalating tensions between India and Pakistan.

The UK has “significant clout and influence on India’s neighbour Pakistan” and could potentially help stabilise regional tensions through increased security cooperation, he said.

His remarks came as India launched missile strikes into Pakistan-administered territory early on Wednesday, claiming to have destroyed “terrorist infrastructure” in response to a recent militant attack in Indian-administered Kashmir that left 26 tourists dead.