India’s manufacturers fear influx of cheap Chinese imports amid US-China trade war fallout

From yarn to steel, India’s domestic industries say they’re being priced out as Chinese firms redirect exports away from the United States

Indian manufacturers are sounding the alarm over a growing influx of low-cost Chinese goods, from yarn and steel to toys and electronics, warning that they are being priced out of their own markets as Beijing redirects more exports away from the United States.

Despite the US and China agreeing to steep tariff reductions last week, analysts warn that years of trade tensions between the world’s two largest economies have already led to a flood of cheap Chinese goods in India and markets elsewhere, leaving local manufacturers struggling to compete.

Earlier this month, the South India Spinners Association reported that at least 50 small spinning mills in southern textile hubs like Pallipalayam, Karur, and Tirupur were facing production slowdowns. Many fear further cutbacks are now on the horizon as raw material imports from China, such as yarn, undercut prices in the domestic market.

The steel sector faces similar challenges. In December, executives from small and medium-sized steel mills, which account for 41 per cent of India’s total steel output, revealed that capacity utilisation had plummeted by nearly a third over the previous six months.

These mills, unable to match Chinese steel priced US$25 to $50 cheaper per tonne on average, have been forced to scale back operations and consider lay-offs, Reuters reported.

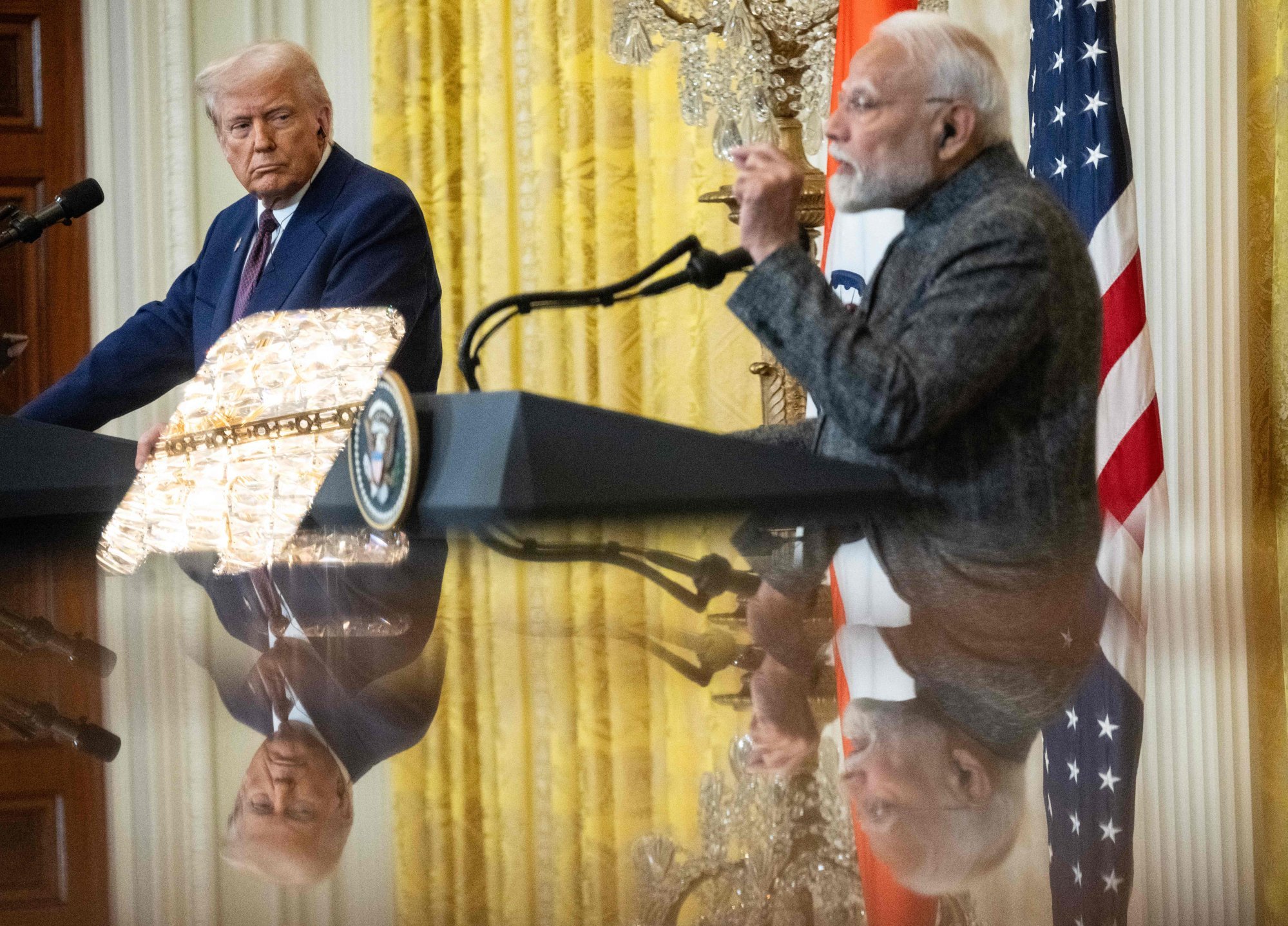

The origins of this upheaval can be traced back to the US-China trade war, which began in 2017 during President Donald Trump’s first term and continued under his successor Joe Biden. By 2024, China’s share of US non-oil goods imports had fallen by nearly 10 percentage points to 16 per cent, according to a report from financial services group Nomura published in April.

However, China’s global export share remained near an all-time high of 15 per cent, the report found, reflecting Beijing’s efforts to redirect surplus trade towards alternative markets.

“China’s highly competitive manufacturers, far from retreating, have penetrated new markets around the globe to make up for lost orders in the US,” the report said.

Strong dependency

Despite border tensions that have varied in intensity since 2020, trade between India and China remains robust. Bilateral trade totalled US$127.7 billion in the 2024-25 financial year, with India posting a US$99.2 billion deficit. Chinese exports to India rose to US$113.5 billion over the same period, while India’s exports to China fell to US$14.3 billion.

India’s reliance on China for raw materials and intermediate goods could intensify as Chinese companies seek new markets for redirected exports, according to economists.

Amitendu Palit, a senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Institute of South Asian Studies, said India’s concerns regarding cheap Chinese imports spanned garments, chemicals, machinery parts, steel, toys and other labour-intensive products.

“The ostensible reason is that high US tariffs and reorganisation of supply chains will force China to use its overcapacity by dumping goods in other markets,” he said.

India has warned local firms against helping foreign exporters bypass US tariffs. Last month, Indian officials said they would set up a monitoring unit to track any surge in cheaper imports from countries like China. Additionally, a 12 per cent “safeguard duty” has been imposed on some steel imports to protect local mills from being undercut.

‘Make in India’?

China has sought to reassure India that it is not dumping cheap products into the country, saying it is complying with World Trade Organization rules and that it is keen to buy more Indian goods.

“We welcome more high-quality Indian products to the Chinese market,” Xu Feihong, China’s ambassador to India, wrote in an opinion piece published by the Indian Express on April 29.

“We will not engage in market dumping or cutthroat competition, nor will we disrupt other countries’ industries and economic development.”

Biswajit Dhar, a trade expert at the Delhi-based Council for Social Development think tank, said India had struggled to boost its manufacturing sector despite Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s “Make in India” initiative.

Central to the initiative is a US$23 billion production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme designed to reward manufacturers for meeting production targets. But progress has been slow and many companies have failed to reach their goals.

As of October 2024, only 37 per cent of the target had been achieved, with firms taking part in the scheme collectively producing US$151.93 billion worth of goods, according to a Reuters report in March.

We need to reduce our dependence on China but we have not been able to find a way outBiswajit Dhar, trade analyst

“The PLI scheme has not taken off as intended,” Dhar said. “There are larger questions at play about why investors have not been forthcoming … compared to China and Southeast Asia, infrastructure is still lacking, hurting India’s competitiveness.”

India has struggled to attract domestic and foreign investors to its manufacturing sector, despite cheap labour giving it a competitive edge. Its services sector, by contrast, has outperformed manufacturing, securing significant foreign investments.

“In terms of manufacturing, we need to reduce our dependence on China but we have not been able to find a way out,” Dhar said.

Even as major US firms like Apple have ramped up investments in India to diversify their supply chains, analysts say that this has led to greater reliance on Chinese components, particularly in tech manufacturing, such as smartphones.

“Heavy domestic demand for inputs and final items in these sectors continues to [help] maintain the reliance on Chinese imports,” Palit said.

Ultimately, rising imports from China could derail India’s ambitions to strengthen its supply chains and make the “Make in India” vision harder to achieve, he said.

Additional reporting by Reuters