In the heart of ‘Silicon Malaysia’, spiralling living costs dent big chip dreams

Despite headline-grabbing investments, factory workers in Kulim struggle to make ends meet as the cost of rent and other essentials surges

At a quiet coffee shop on the outskirts of Kulim’s sprawling industrial zone, Azmin unscrews the cap of his mineral water bottle, exhales deeply, and reflects on the gap between the ambitious promises of “Silicon Malaysia” and the reality on the ground.

From his vantage point as a recruiter for one of the region’s fastest-growing semiconductor production hubs, the tech sector’s promises of abundant job opportunities feel hollow.

“We haven’t had much demand lately,” Azmin told This Week in Asia, requesting to be identified by only his first name for fear of losing future business. “The last round of recruitment we handled was a few months ago for 20 people at a smaller factory.”

While the government paints a picture of booming industry and economic transformation, Azmin sees another side of the story. Development has raised land prices, with houses and rents surging in an area that was once oil palm plantations and farmland.

The result has been good for property speculators, but bad for everyone else, he said. A decade ago, Azmin bought a modest home for 95,000 ringgit (US$22,100). Today, similar houses fetch at least 300,000 ringgit.

Kulim Hi-Tech Park, established 30 years ago, was built on 5,600 acres (2,300 hectares) of cleared farmland to support Penang’s semiconductor boom. Azmin’s family, originally from Penang, were among the first to spot the park’s potential.

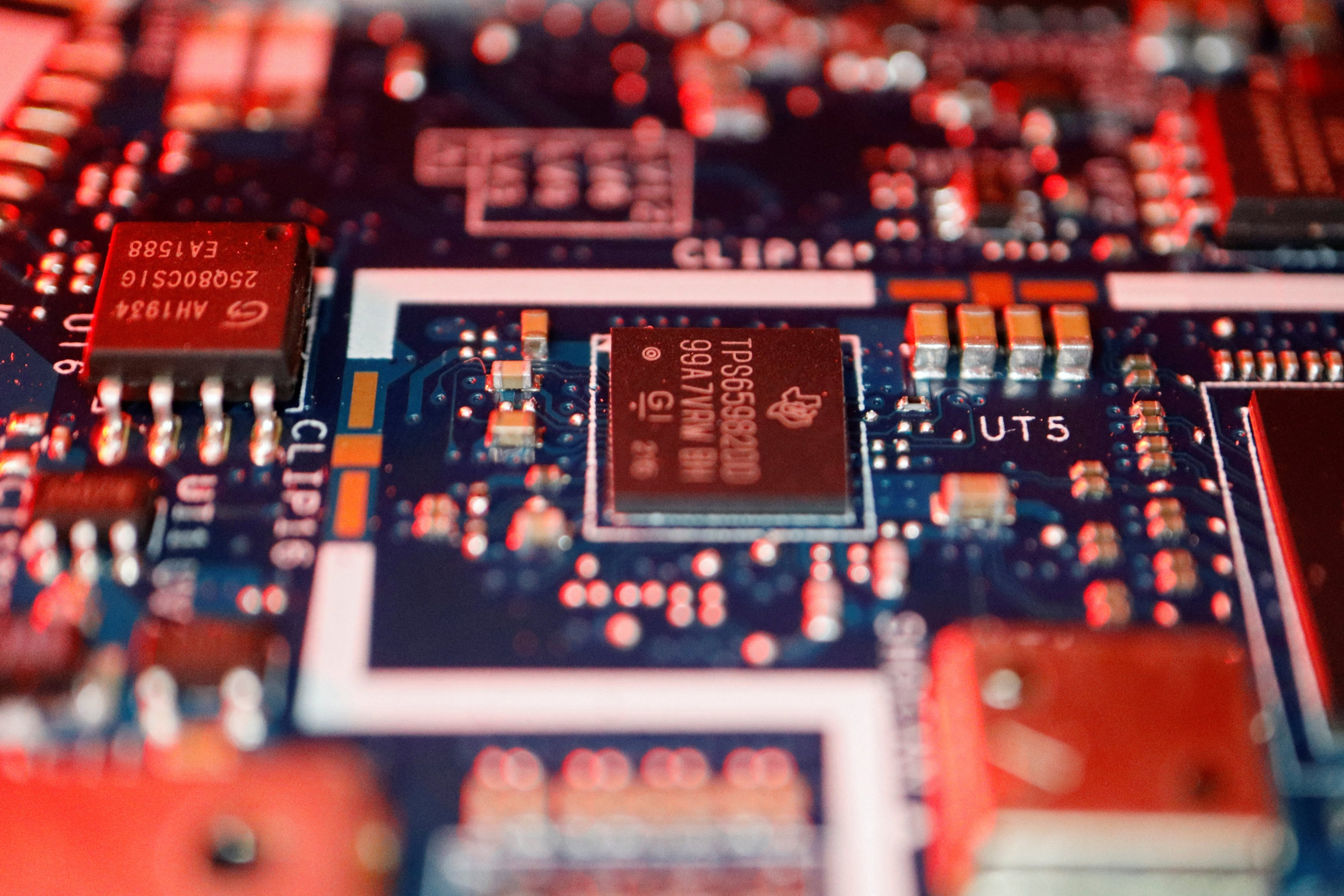

Over the years, big names like Austria’s AT&S and German chipmaker Infineon have moved in. Infineon last year pledged €5 billion (US$5.6 billion) to expand its facility, while AT&S recently launched a 5 billion ringgit (US$1.2 billion) plant in the park.

But for many, these headline-grabbing investments do not translate into prosperity.

“It’s good that there are jobs, but factory workers earn just 1,700 ringgit,” Azmin said, referencing Malaysia’s minimum wage. “Renting a place in Kulim will cost at least 700 ringgit now. If a factory worker has a wife and two children, they won’t have anything left after spending on necessities.”

Kulim, home to about 120,000 people, was hit hard by pandemic-era lockdowns and has struggled to recover from the economic scars of Covid-19. Official figures show nearly 10 per cent of the district’s population lives in poverty.

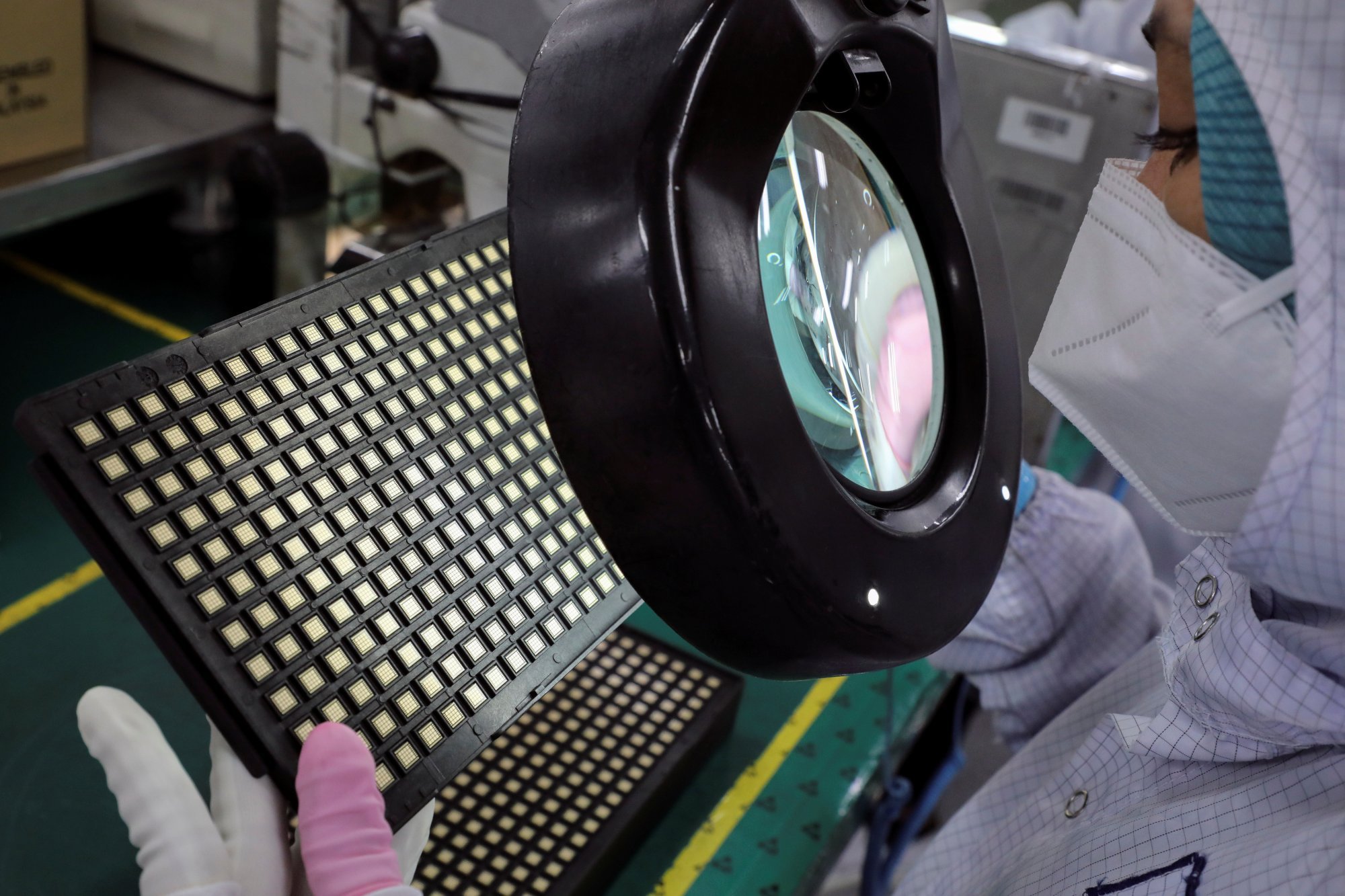

But industry leaders argue that the tech sector offers some of the best pay in Malaysia. Workers in the electrical and electronics sector earn double the national average wage, according to the Malaysian Semiconductor Industry Association.

“With competition [in the industry], salaries will continue to move [upwards],” said the association’s president, Wong Siew Hai.

AT&S reports that entry-level engineers at its Kulim facility earn starting salaries of around 5,000 ringgit, while it says factory line workers take home over 3,000 ringgit a month – well above the minimum wage.

Resource drain?

Malaysia’s government aims to attract 500 billion ringgit (US$116 billion) in semiconductor investments and produce 60,000 engineers and technicians by 2030.

Kulim Hi-Tech Park management announced plans in November to double its area to 12,000 acres (4,900 hectares), highlighting the high demand for industrial space.

However, rapid industrialisation comes at a cost. Semiconductor plants and data centres are notoriously resource-intensive, consuming vast amounts of electricity and clean water.

Malaysia’s water services commission warned earlier this year that existing data centres were already pushing water supplies to the brink. In Selangor, Negeri Sembilan and Johor states, the 101 data centres present collectively require 808 million litres (213.5 million gallons) of water daily, yet current infrastructure can only supply less than 20 per cent of that demand.

The issue is not a lack of rainfall – Malaysia receives more than 970 million cubic metres (34.3 billion cubic feet) annually – but rather poor water management.

“We are already experiencing serious water issues despite the fact that we are water rich,” said Chan Ngai Weng, president of conservation group Penang Water Watch.

Chan stressed the need for industrial users to adopt sustainable practices, including water recycling and rainwater harvesting. Without these measures, he warned, the rush to expand industrial capacity could leave household taps dry.

“Silicon Malaysia” may yet deliver on its promises, but for Kulim’s workers and small businesses, the benefits so far are unevenly distributed. In the race to build the future, who will be left behind in the rush for progress?