In Singapore, ‘third places’ tap into yearning for deeper physical connection in digital age

Casual Poet Library, Stranger Conversations among community-led initiatives in city state to encourage greater in-person interactions

When Rebecca Toh posted on social media in May 2024 to gauge interest in a community-run library in Singapore, she was surprised by the overwhelming response. It quickly became clear that the idea resonated not just because of a love for books, but because it tapped into a deeper yearning among Singaporeans for connection.

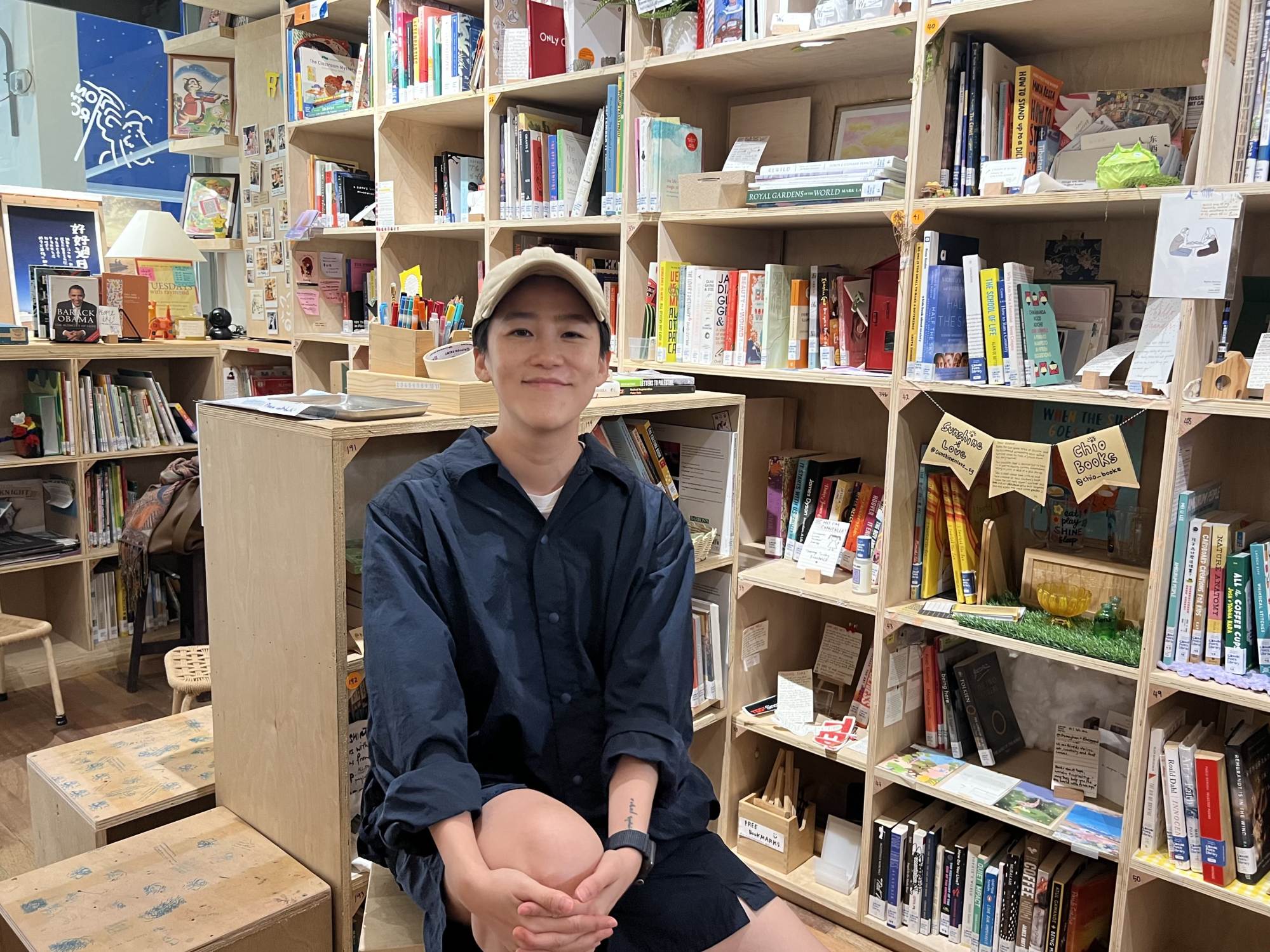

Less than three months later, Casual Poet Library opened at the void deck of a neighbourhood estate in Bukit Merah, fully funded by the community and run by volunteers.

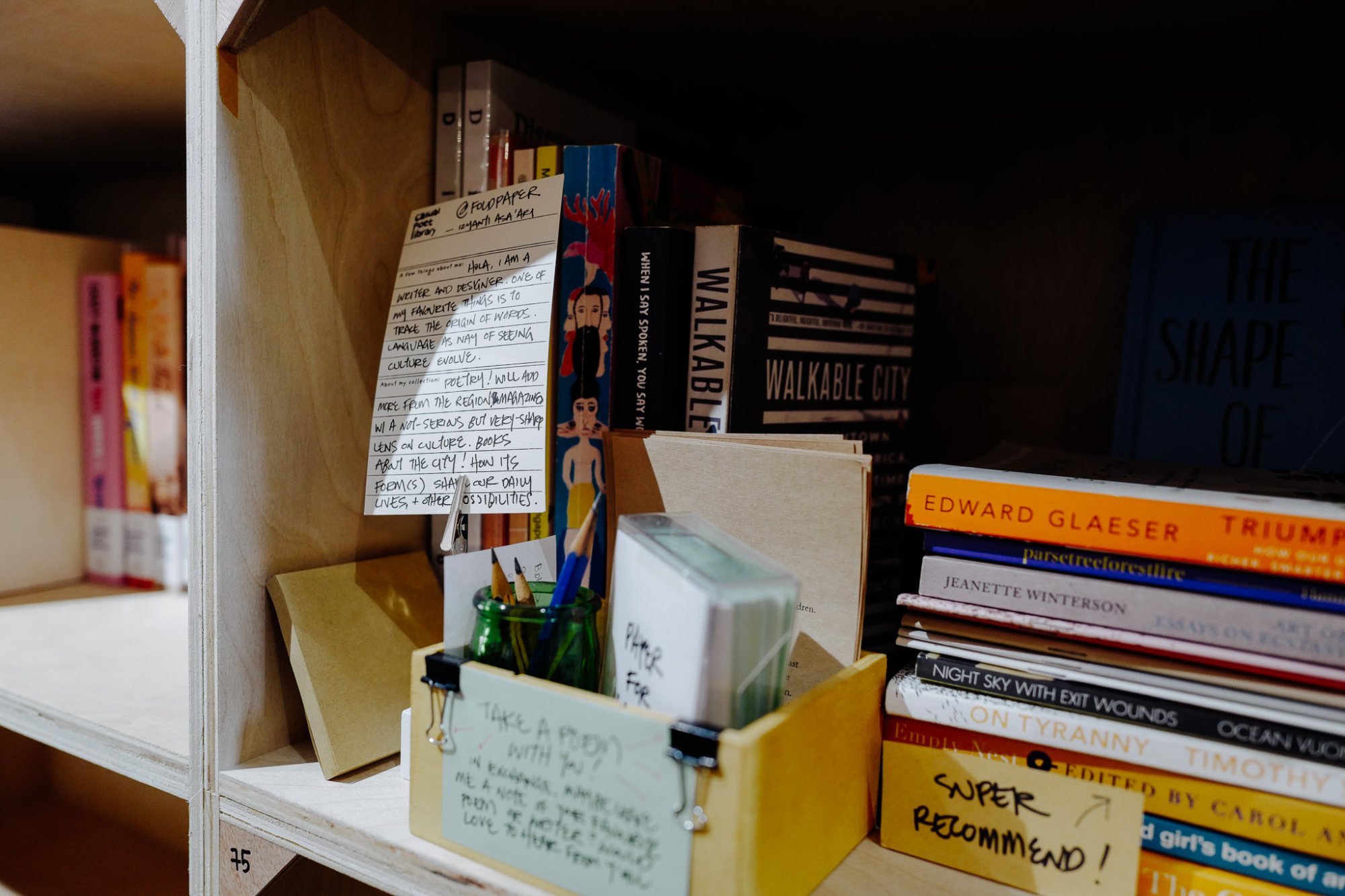

The cosy 450 sq ft space is lined with bookshelves, where people rent shelf space to share their personal collections. Many include handwritten notes or self-introductions, inviting visitors to connect and strike up conversations.

“It’s a kind of community centre slash living room,” Toh said. “You find something or someone that you connect with here.”

In Singapore, a growing number of millennials and Gen Zs are actively seeking out and creating their own communities to meet new people. Across the island, such “third places” – locations for informal socialising beyond work and home – are on the rise.

Casual Poet Library, which is open to the public and hosts regular events from book clubs to craft markets, is a prime example.

“These places are not fancy or expensive,” said Ho Kong Chong, head of urban studies at Yale-NUS College, distinguishing them from social spaces with hefty membership fees such as country clubs.

As people visit third places regularly, they become “familiar strangers”, he added.

These places thus offer a valuable opportunity to connect with individuals from diverse backgrounds, fostering interactions that might not otherwise occur, particularly in Singapore where people are typically more reserved and maintain fixed social circles.

“The conversations are addictive,” Ho told This Week in Asia. “We’re so used to our closest friends that before you talk to them, you already know what the answer is. But when people come from different walks of life, conversations get quite interesting.”

This same ethos fuels Stranger Conversations, a project born from founder Ang Jin Shaun’s personal quest to hear from individuals who had veered from the conventional.

His conversations with them, such as a former tech worker now dedicated to girls’ education in Nepal, and a neighbour who started a vegan cafe from her flat after a van trip from Singapore to Thailand, eventually evolved into public sharings. That was when Ang noticed a hunger for more.

“People were actually staying back and mingling after the events, even the [speakers] became a participant in that way,” said Ang, adding that many stayed for more than two hours after events ended just to chat. “People were just so interested in each other.”

The recognition led to the current Stranger Conversations, housed in a unit at local creative enclave 195 Pearl’s Hill Terrace. When not hosting a diverse range of events, the welcoming space functions as a living room for reading, co-working or simply hanging out, open to anyone who walks in.

For regulars like Benjamin Yap, 32, the physical presence of Stranger Conversations is its core appeal, especially in comparison to fleeting interactions on social media.

“Stuff only happens when you physically engage with people,” said Yap, who first came for a meditation event last September and, intrigued by the conversations he had there, returned.

He now hosts his own projects in the space, including a podcast featuring people he meets within its walls – often for the very first time.

Beyond inspiration and collaborations sparked by in-person encounters, these physical spaces also address a fundamental human need: to counter loneliness.

“Every event is an excuse to be with other people,” said Yap, recounting how the strong human desire for connection helped an initially anxious attendee at an event overcome his discomfort in a room full of strangers.

And in today’s digitally dominated age, the sensorial experience of being in a physical space offers something that online communities cannot replicate.

“You touch, you smell and you taste. Those kinds of things are very powerful. They engage you and they can be the stuff of conversations,” said Ho from Yale-NUS College.

Casual Poet Library’s Toh agrees, asserting that these physical spaces will only grow in importance as the world becomes increasingly digital.

“The internet was supposed to bring us closer together, but it seems to have made us feel more disconnected from other people and also from ourselves,” she said, noting that many visitors were young digital natives.

This desire for tangible interactions is clear in the library, as people flip through physical books, exchange handwritten notes, or share a conversation with another stranger over coffee.

Volunteer librarian Maisie Cheong first met Toh in an online book club during the pandemic, when physical gatherings were largely prohibited. While the two hit it off, it was difficult to foster that same level of connection within the broader online community since conversations often lacked the organic upkeep needed to truly take root.

The birth of the physical library was thus particularly meaningful for Cheong, who now runs monthly book clubs where conversations delve deeply into personal experiences within the space.

And the ground-up nature of spaces like the library and Stranger Conversations highlights the power of community-led initiatives.

“People are starting to mould the society that they want,” Cheong said. “That’s how we can get the most powerful spaces, because we’re creating what we need ourselves.”

In contrast to some public third places that might be constrained by strict regulations or conditional funding, these grass-roots efforts offer a greater degree of self-determination.

For Toh, this autonomy was key – taking the leap to start the community library, prioritising connection over profit in a city often driven by the latter, felt almost like an act of rebellion.

Fees collected from renting its shelves and space for events help cover the library’s rent and provide some financial flexibility, giving her confidence in its future.

“I wanted to rethink what community space can be and what us, very small individuals, can do,” Toh said.

“We might think we’re quite powerless, but maybe it doesn’t take a lot to build something together.”