In quiet rebellion, Malaysians push back against book bans

Book lovers lament being at the mercy of ‘faceless officers’ who decide what the public can read, as the number of banned titles grows

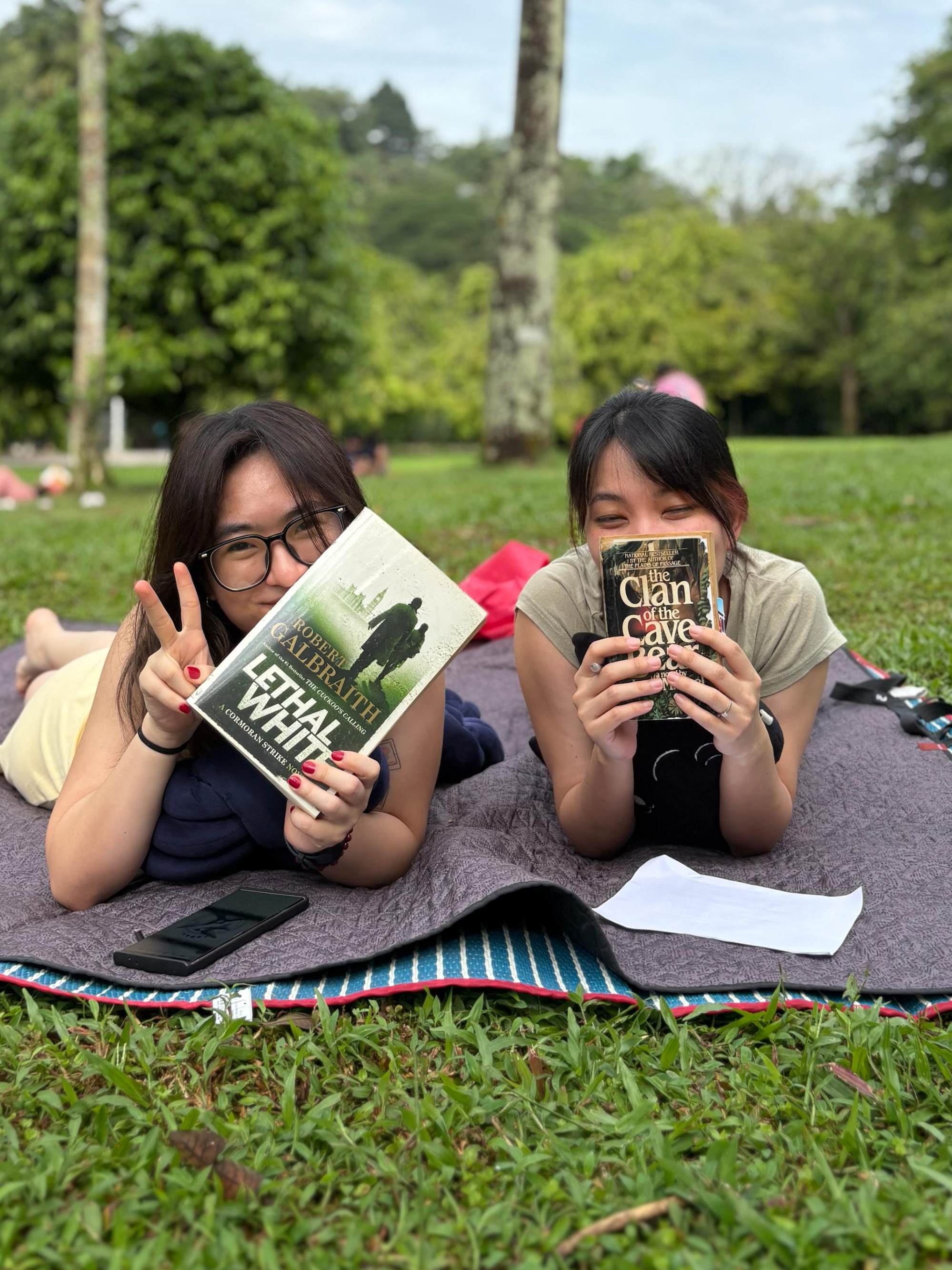

Across cities in Malaysia, groups of people have begun quietly gathering in parks to read – no discussion, no assigned texts, just shared silence and books. In Kuala Lumpur’s botanical gardens, mats are unfurled beneath the trees as readers lose themselves in novels, forming a ritual that has quietly caught on.

It is one of several signs pointing to a revival in the country’s reading culture. Yet even as Malaysians flock to book fairs and devour literature in record numbers, a parallel surge in state censorship has left writers and readers alike wondering what, exactly, is being protected – and from whom.

So far this year, authorities have banned 12 books – more than double the total outlawed in the past two years combined. The sudden spike has alarmed freedom-of-expression advocates and sent shock waves through Malaysia’s literary community.

Among the blacklisted titles is The American Roommate Experiment, a bestselling romantic comedy by Spanish author Elena Armas, which follows a woman who leaves her high-paying job to pursue her dream of writing romance novels.

Also banned is Love, Theoretically by Italian neuroscientist-turned-author Ali Hazelwood, whose fiction often centres on women in academia and the sciences.

Local romance novels have not been spared either. Mischievous Killer by local author Ariaseva and Tuan Ziyad: Forbidden Love by Bellesa have also been swept up in the crackdown.

While religious content and LGBTQ themes are commonly targeted, the criteria for censorship are opaque – and seldom explained.

Book bans had declined from a peak of 70 titles per year under scandal-plagued former leader Najib Razak. But the recent resurgence under Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim suggests a pivot back to a more repressive era in this country of 34 million.

It comes despite Anwar’s own remarks at the recent Kuala Lumpur International Book Fair, where he lamented the nation’s lack of a strong reading culture and declared: “Our duty is to enrich and promote the culture of reading.”

For Malaysian writer and publisher Mutalib Uthman, the contradiction is personal. His satirical work Orang Ngomong Anjing Gong Gong was banned in 2016, along with three other titles from his publishing house, DuBook Press.

“Books are not meant to be published to universal appeal,” he said. Not one to mince his words, Mutalib said Malaysian readers were at the mercy of “faceless officers” who arbitrarily decided what was acceptable.

“We the readers end up losing when vague, opaque, and clueless officers like these become the decider,” he said.

Censorship falls under the jurisdiction of the Home Ministry’s Publication and Quranic Texts Control Division, which regulates all printed materials – books, magazines and religious texts alike – to ensure compliance with Malaysia’s legal and moral codes.

The legal framework underpinning this authority is the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984, which grants the home minister sweeping powers to prohibit any publication deemed “prejudicial to public order, morality or national security”. Violators can face fines or up to three years in prison.

According to the ministry’s blacklist, published on the government’s official gazette, 12 titles were banned between January and May this year – surpassing the five and six titles that were banned in all of 2023 and 2022, respectively.

Many of the recent targets are mainstream romance novels by foreign authors, leaving publishers, and readers, guessing at what unseen line may have been crossed.

Repressive chapter

This pattern of censorship is not confined to books. In recent years, the government has threatened to shut down concerts mid-performance using a “kill switch”, censored films and seized goods it deems inappropriate.

In 2023, the Home Ministry made international headlines after banning all Swatch watches featuring LGBTQ motifs. The move came months after the tightly contested 2022 general election, which saw a swing towards conservatism among voters.

Analysts say this has prompted Anwar’s government to adopt policies that appeal to the Malay Muslim majority – often by engaging in culture wars in an attempt to outflank the growing influence of Islamist hardliners.

Although the law allows aggrieved parties to file for judicial review, the home minister retains absolute discretion. Reversals are rare.

One exception came in November when Swatch successfully challenged the seizure of its watches. The court ruled the action illegal and ordered the merchandise returned – though the official ban remains in place.

Article 19, a global free speech watchdog, has called the government’s continued censorship “deeply troubling”.

“It is well known that this law grants arbitrary powers and has often been used to suppress those critical of the government and curtail freedom of expression in general,” said Nalini Elumalai, the group’s senior programme officer for Malaysia.

The Home Ministry defends its actions as preventative, aimed at safeguarding public order. Responding to a 2023 raid on a bookstore in Kuala Lumpur, Home Minister Saifuddin Nasution said the ministry acted on complaints.

“When there is a complaint from the public, certainly the enforcement and control section of the Home Ministry will use the relevant clauses from the act to visit the premises that are complained about,” Saifuddin said.

Still, the backlash continues. When Australian author Scott Stuart had his children’s book My Shadow is Purple banned in January, he responded by launching a literary prize “to help more books like this exist”.

For many Malaysians, the bans feel less like protection and more like political theatre aimed at appeasing a conservative base. Since taking office in November 2022, Anwar has been accused of pandering to such sentiments.

Actor and playwright Na’a Murad said the arts had long been a convenient scapegoat for politicians eager to appear morally upright.

“As usual, it doesn’t matter who you vote for, the creative arts become the whipping boy for performative moral stewardship,” he said.

‘What’s the big deal?’

Yet even as censorship tightens, Malaysia’s reading culture is experiencing a revival.

Signs of that growth are everywhere. This year’s Kuala Lumpur International Book Fair, which wrapped up on June 1, attracted more than 2.1 million visitors over nine days. In Penang, the George Town Literary Festival continues to draw international talent, including Indonesian novelist Eka Kurniawan, Kenyan-American author Mukoma wa Ngugi, and writers and poets from Japan and Germany.

Indonesian author J.S. Khairen, attending the Kuala Lumpur book fair, marvelled at the turnout.

“All the hotels around here are full because people are coming here to buy books,” he said on TikTok. “Imagine, this is a country where whole families devour books.”

In neighbouring Indonesia – where cultural and religious sensitivities often mirror Malaysia’s – novels are powering a booming film industry. Gadis Kretek (Cigarette Girl), an adaptation of Ratih Kumala’s novel, became a hit on Netflix and was widely praised in both nations.

Malaysian novelist Neddo Khan, who recently released a self-produced film adaptation of her young adult novel Gantung, said such creative pursuits were largely stifled in Malaysia.

Asked about the book bans, her response was a terse “ridiculous”.

She recalled reading titles as a teenager that were condemned for vulgar language or political themes – books she sought out precisely because they were controversial.

“This happens when you try to ban a book: people will just look for it more diligently,” Neddo said. “At 15, I went, ‘I don’t get it. What’s the big deal?’ And I still feel the same way about banned books at 40.”