How Singapore can help China build bridges in an age of fracture

If it chooses to embrace its strengths, Singapore is one of the few actors trusted enough to lay the foundation for a more just global order

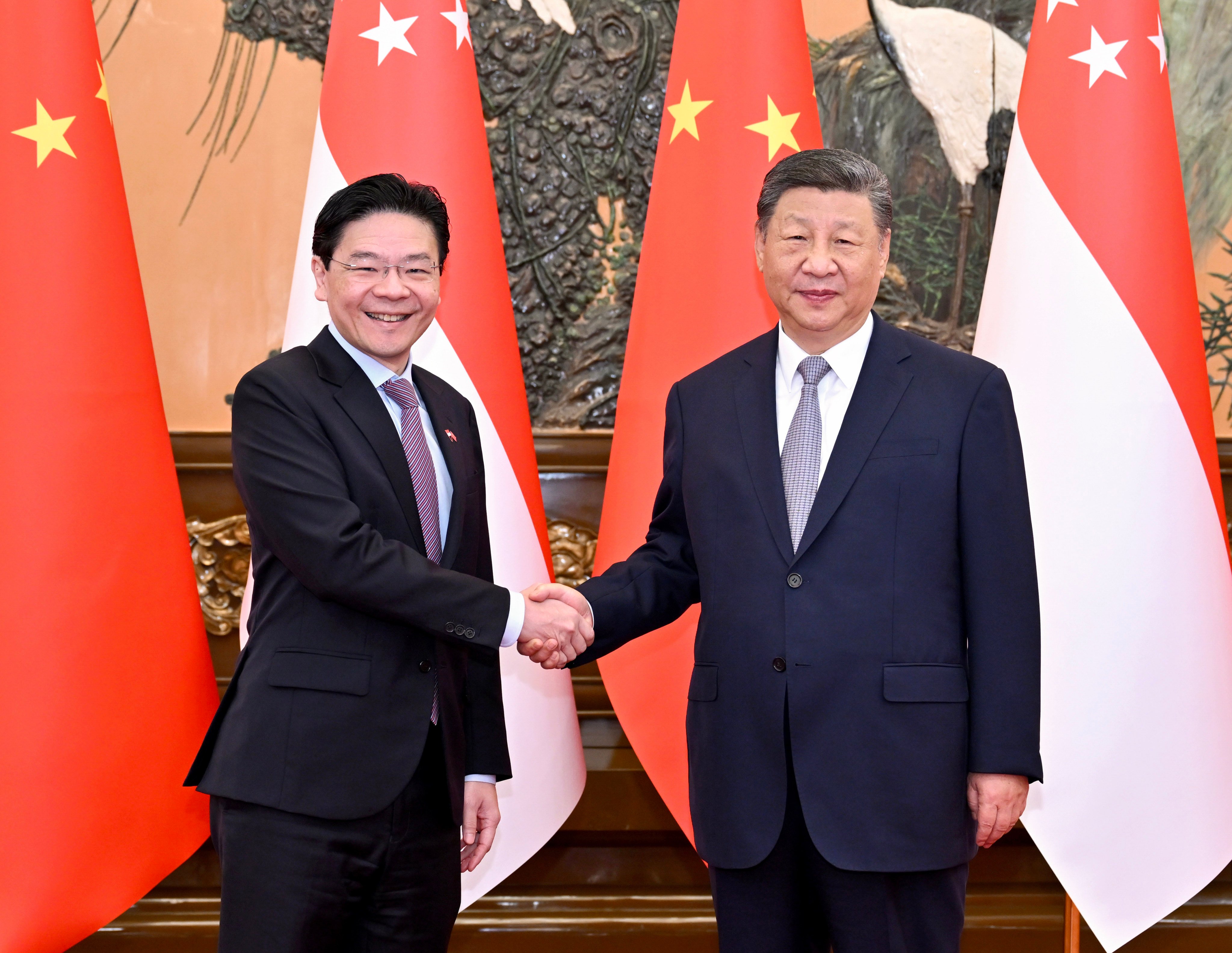

The recent visit of Singaporean Prime Minister Lawrence Wong to China reaffirmed the strategic depth of the China–Singapore relationship. His meetings with Chinese leaders underscored a readiness to work together to uphold the principles of free trade and multilateralism.

But beyond symbolism, this visit raised critical questions. What role will Singapore now play on the global and regional stage? What new possibilities does this moment unlock?

As geopolitical rivalry hardens and the risks of global fragmentation grow, Singapore’s strategic position as a mediator, convenor and facilitator is becoming more important. Rather than simply hosting dialogues or taking part in frameworks, Singapore must step forward and shape them. It can draw on its unique positioning: rooted in Southeast Asia yet globally engaged, trusted by both East and West and respected for its competence, discretion and policy independence.

Consider the opportunities presented by Wong’s visit, including expanding training programmes between the Singapore and Chinese governments and helping export the joint business management, shared investment and industrial zoning model of the Suzhou Industrial Park. Singapore is already adept at blending governance expertise with China’s industrial scale.

These initiatives must not remain technocratic exercises. They should serve as platforms to elevate standards in transparency, sustainability and local empowerment across countries along the Belt and Road Initiative. Singapore can help redefine connectivity, not as a contest of influence but as a laboratory for inclusive development.

Singapore has long navigated a careful path between China, its largest trading partner, and the United States, its foremost security partner. This balancing act is about more than survival – it is about leverage. Wong’s trip to Beijing affirms that Singapore is not a bystander in great power competition, it is a potential promoter of shared frameworks that reduce risk and enable cooperation, even amid rivalry.

This can be seen in how Singapore helps steward flagship bilateral projects, from the Suzhou Industrial Park to the Tianjin Eco-City and the Chongqing Connectivity Initiative. But the next step lies in scaling these examples into replicable multilateral models to other parts of the world. Singapore should help translate its experience into formats that align Chinese capital and technology with international development goals, particularly in the Global South.

Likewise, Singapore’s efforts on the multilateral stage merit greater ambition. It has been a pioneer in digital governance, trade facilitation and sustainable finance. As a founding signatory of the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA), it has set new standards for data flows, platform interoperability and digital trust. With China formally applying to join the DEPA, Singapore has the opportunity to promote Beijing’s integration into an international digital rule-making network.

Similarly, Singapore’s role in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership follows a similar logic. As a founding member, it should continue to offer technical and diplomatic support to aspiring members such as China while reinforcing the pact’s high standards. The goal is not merely expansion for its own sake but meaningful convergence that strengthens regional trust.

But Singapore’s most vital contribution might lie beyond formal agreements. It has the rare ability to mediate across divides, not only between states but also between institutions, sectors and civil societies. The world today suffers from a deepening trust deficit: between governments and the public, between the Global North and South, and between Western societies and Chinese institutions. Singapore is uniquely placed to help bridge these gaps, enhancing exchanges between East and West.

Singapore can foster peaceful understanding and facilitate cooperation by convening cross-disciplinary meetings and engaging stakeholders from across ideological divides. As negotiations between China and Southeast Asian nations continue over a South China Sea code of conduct, Singapore’s commitment to dialogue positions it to support the speeding up and enactment of an agreement. In addition, Singapore facilitated a meeting in 2015 between President Xi Jinping and Ma Ying-jeou, Taiwan’s leader at the time, the first time both sides’ leaders had met since 1949.

Beyond diplomacy, Singapore can also translate technical work on maritime law, regional governance or military risk reduction into actionable frameworks. Its multilingual and multicultural strengths and trusted reputation make it uniquely capable of contextualising narratives across diverse audiences. In an age of information silos and geopolitical mistrust, this combination is both rare and essential.

This extends to its think tanks, professional networks, universities and even media institutions. Singapore can become the preferred venue for informal dialogue between Chinese and Western experts, less politicised than Washington and more convenient than Beijing. Such multichannel diplomacy will become indispensable as great power competition intensifies.

Singapore must also reinforce its unique role in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. This mediating role allows it to help shape the norms and structures of the post-unipolar world. In this context, Singapore can position itself as a central node – flexible, principled and proactive.

Of course, this is not without risk. Singapore’s strength lies in its credibility, and credibility must be continuously earned. Its challenge now is to show that it can navigate complexity and offer solutions that are pragmatic, scalable and fair to the dilemmas of interdependence.

As China continues its own process of internationalisation, and as the world confronts shared crises, the need for trusted interlocutors is greater than ever. If Singapore can use this moment to expand its convening power, institutional imagination and agenda-setting capacity, it will reinforce its relevance and help stabilise a volatile region.

Building bridges is more than a metaphor today – it is creating the infrastructure for peace. If it chooses, Singapore is one of the few actors trusted enough to help lay its foundation.