How China’s diaspora became both an asset and a source of anxiety

Once marginalised, overseas Chinese have become a vital bridge for China – and a lightning rod for global tensions

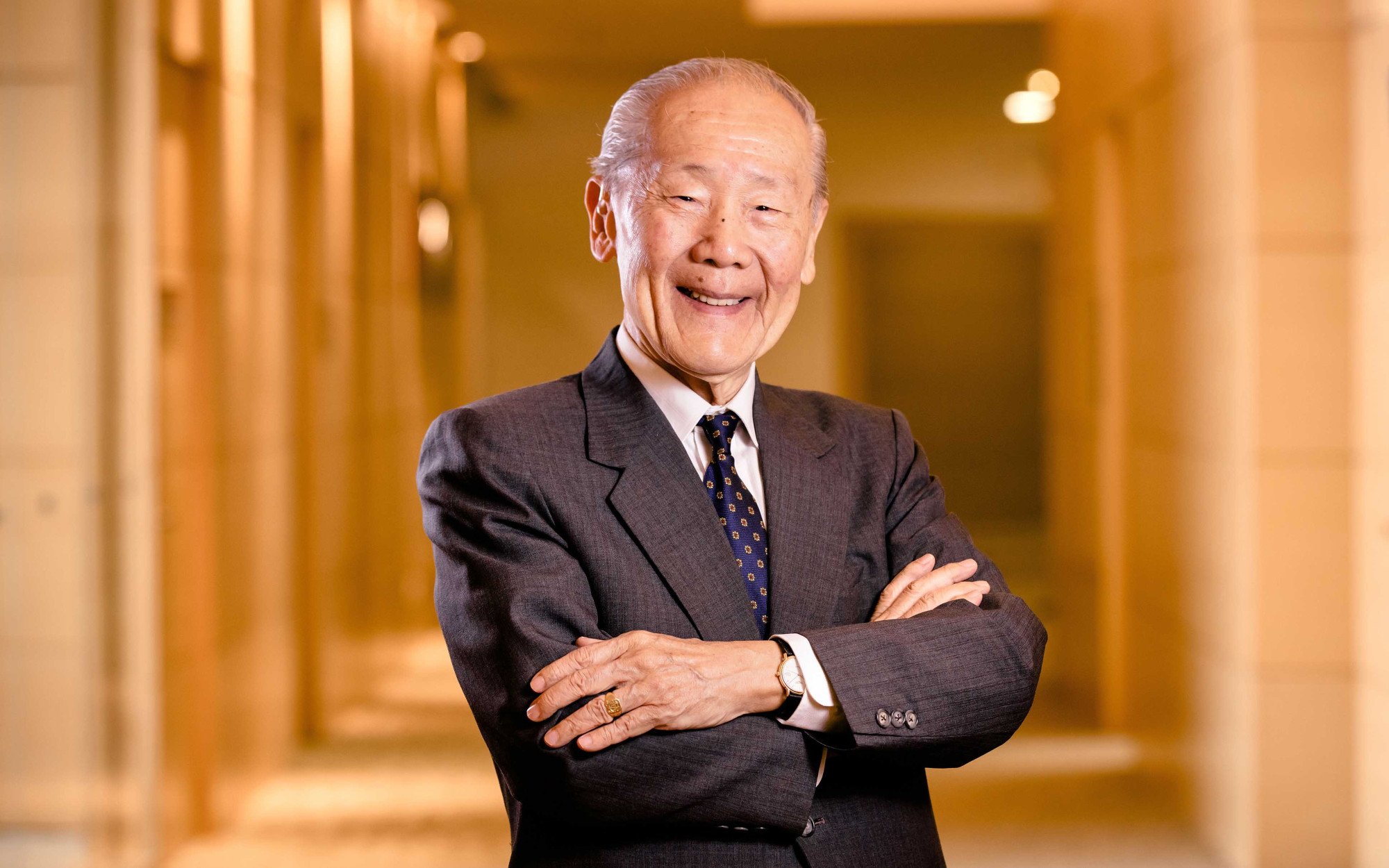

Wang Gungwu – one of Asia’s most respected historians and a pioneering scholar of the Chinese diaspora – explores in Roads to Chinese Modernity: Civilisation and National Culture how China evolved into a modern nation navigating reform and globalisation. In this excerpt, Wang traces how, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, reformers and revolutionaries such as Kang You-wei, Liang Qichao and Sun Yat-sen began rallying support from overseas Chinese communities. Once dismissed as disloyal exiles, these migrants soon came to be seen as both a strategic asset and a political risk in China’s rise.

The overseas Chinese attracted wide attention when political figures like Kang You-wei, Liang Qichao and Sun Yat-sen reached out to engage them about the future of China. Whether the message was to seek reforms or to overthrow the regime, these Chinese were responsive to the calls for help.

Some of those who had recently come from China had anti-Manchu backgrounds, while others were ashamed that it was repeatedly defeated by the West, and alarmed that China was backward and getting poorer. This not only affected their pride but also their status and security abroad, especially those who already felt discriminated against in one way or another. Even though some in the Southeast Asian colonies became rich despite this, they were successful only because they were very adaptable and willing to take many risks. Many others were not so fortunate and ended up destitute.

Under the circumstances, the more successful merchant classes were ready to help their idealistic kinsmen from their birth country to connect the outside world with China and help it become modern and competitive. As a result, more Chinese officials and politicians became aware that these external communities could be assets in China’s future development.

It is interesting to recall that Europeans trading in Southeast Asia had long been conscious of the range and vitality of Chinese entrepreneurship. From the 16th century on, Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and later British writers had been describing, some in considerable detail, the valuable role of Chinese merchants, their versatility and skill.

Although none of the studies were systematic, these records led to studies of Chinese potential as partners and competitors, as cheap labour, as immigrants, but eventually also as threats to colonial and imperial interests. Later, and elsewhere in the Americas and Australasia, the reactions were different. Chinese labour was considered cheap and crime-ridden, and for decades the numbers allowed to stay were severely cut down.

During the first half of the 20th century, the Republican Chinese government could do little to help them. Thus, in most of these places, the Chinese who remained had almost become “invisible people”.

As such, during the early decades of that century, it was the Southeast Asia-based overseas Chinese who became particularly significant to the Chinese government. The response from these overseas communities was enthusiastic, notably with the establishment of modern media outlets and schools that were politically committed.

These were so successful that their activities began to be a source of alarm among the colonial administrations and, increasingly, also of the nationalistic local leaders. With growing numbers of Chinese arriving in Southeast Asia or Nanyang, the study of overseas Chinese took on new dimensions.

The subject became significant also with the authorities in China after the revolution in 1911. The transfer from a Confucian dynastic state to a modern republic itself demanded fresh thinking. Most Chinese did not understand what a republic was, but they knew that embarking on the process of modernisation required a major cultural transformation. To catch as progressive and developed as the very-powerful West was necessary if China was to free itself from dominance by the foreign imperial forces active on its coasts.

Chinese leaders realised that the country was starting from a very low base. Their defeat by Japan in the late 1890s was an eye-opener. Japan showed how to modernise quickly and the Chinese saw that they too could do the same. But it was not easy. China was exposed to greater internal divisions and, during the warlord period, the country weakened even more rapidly. Then came the Kuomintang’s war against the Communist Party, followed by the Japanese invasion in World War II. For over 30 years, the Chinese state controlled less than half of the country, and its financial affairs were burdened by growing debt as the economy steadily shrank.

Republican China was more divided than in the last years of the Manchu Qing dynasty. The weakest moment came during the course of the Sino-Japanese War from 1937 to 1945. Were it not for the intervention of the Western powers after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour and the invasion of Southeast Asia, most of China would have fallen and the country could have become a bundle of puppet states of the Japanese Empire. By itself, China could not have won the war.

During those decades of weakness, the reactions of overseas Chinese became more important. Many of the communities volunteered to support the national salvation movement, a sort of external frontline for a heightened nationalism to save the country from destruction – not only China as a country but also as a civilisation. Born in 1930, I am old enough to remember growing up in that atmosphere of fearing that the country would be completely defeated.

Then, there was a sea change in the way the Chinese saw themselves. Before this, most felt that what they shared was a common set of cultural values and had not known China as a nation. Now, they saw that the country had to become a modern nation-state. But what was normal was still to think in terms of their hometowns, families and particular groups and localities where their personal commitments lay.

The idea of China as a great ancient civilisation was vague. The literati classes had defined that, but there was a great gap between the small group of elites and the bulk of the ordinary people who lived rural lives in an agrarian economy or made a living in commerce. Even when that changed among those overseas, and when more people in China became competitive in the coastal ports and began to understand the capitalist economy, there was still a large competence gap that had to be bridged.

Uncertainty surrounding loyalties

Given these disadvantageous conditions, it would have been very painful for China to transform itself. With the added problems of civil wars and invasions, and with continued economic displacement by foreign economies taking advantage of the treaty concessions, the various republican governments simply could not overcome the difficulties they faced.

It was under those circumstances that the role of the overseas Chinese gained importance to all concerned. They were drawn into the politics of China. Many Chinese leaders went out to engage the communities overseas and get them to support those in power or to deter those who were seeking to replace the regime. The term “patriotic huaqiao” became widely used wherever overseas Chinese were living.

This development did have negative results, especially in Southeast Asia, where former colonies began to establish new nation-states. After the Second World War ended in 1945, most overseas Chinese were joyful that China was united again, even when it was the Communist Party that won the civil war on the mainland. Although not every Chinese abroad was nationalistic, the outside world and the Chinese government saw them as closely linked to the future of China.

In the postcolonial nation states, nation building had the highest priority. Nationalism developed in every country that had been colonised, all now (at least in theory) equal members of the United Nations. In this new world, Chinese nationalism was not welcomed and, among some of the local nationalist leaders, the new Chinese government in Beijing was highly suspect.

In Southeast Asia, the concept of the overseas Chinese went through a period of depoliticisation or denationalisation, during which many Chinese families had to endure very difficult conditions to adapt to new relationships with local national leaders.

As it turned out, the Chinese, more than any other migrant peoples elsewhere, became victims of the ideological Cold War that spread to the region. The nationalistic overseas Chinese who were happy to see China united came now to be treated as potential fifth columnists for Red China.

As far as I know, no other major migrant group has been put in this doubly tainted position, in which their ties with their homeland opened them to distrust for questionable loyalties, as well as to fear for their ideological proclivities, both at the same time. That was why the subject of overseas Chinese became, for quite a while, a sensitive subject, not merely among them, but also among officials of the governments that were concerned about their Chinese communities.

In that context, the subject divided the Chinese communities abroad among those who were linked to the People’s Republic, those who looked to Taiwan and those who tried to demonstrate local loyalties in their respective adopted countries. For two decades in the 1960s and 1970s, the subject of overseas Chinese was taboo and scholarly research was very thin. Within many countries, it had to be played down because it was either anathema to local nationalists or subversive to anti-communists.

There were moments when the subject almost died out among the Chinese themselves and was only of interest to foreign historians and anthropologists. I recall this as a time when only a few among the Chinese overseas would take the trouble, or run the risk, to keep the subject alive. I want to mention one of them because he was the most persistent and deserved all the credit he received.

I refer to Leo Suryadinata, a former president of ISSCO (International Society for the Study of Chinese Overseas). He did his work on the Chinese Indonesians when the subject was one of the most sensitive anywhere in the world. He continued his writings and research when almost no one was paying much attention. I followed his efforts with interest, not only because they were important, but also because his writings helped me understand what other Chinese communities were undergoing elsewhere in the Southeast Asian region and even in other continents.

It is interesting that attitudes elsewhere in North America and Australasia began to change from the 1960s and their “invisible people” began to speak proudly of their Chinese ancestry. Ethnologist Wang Ling-chi would agree that I should single out Mark Lai (Mai Liqian) as the pioneer who set the community recovery process going in the United States. Ironically, once research began, the scholars found that records were better preserved and there was less sensitivity about the subject than in Southeast Asia, where many more Chinese had made major contributions to the region’s development.

By the 1980s, conditions began to change again. Before that, most Chinese were adapting themselves to new conditions, settling down and showing how they were loyal to their nation-states and seeking new ways to deal with a China going through the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution. They focused their energies on activities useful to their adopted countries, notably in commerce and industry.

It was significant how many of the new nation-states did not want their citizens of Chinese descent to be active in politics or dominate their professions, but preferred to let the Chinese make money, especially for the country. That was the one area where the Chinese were left with more room to develop and be regarded as least harmful to nation-building programmes.

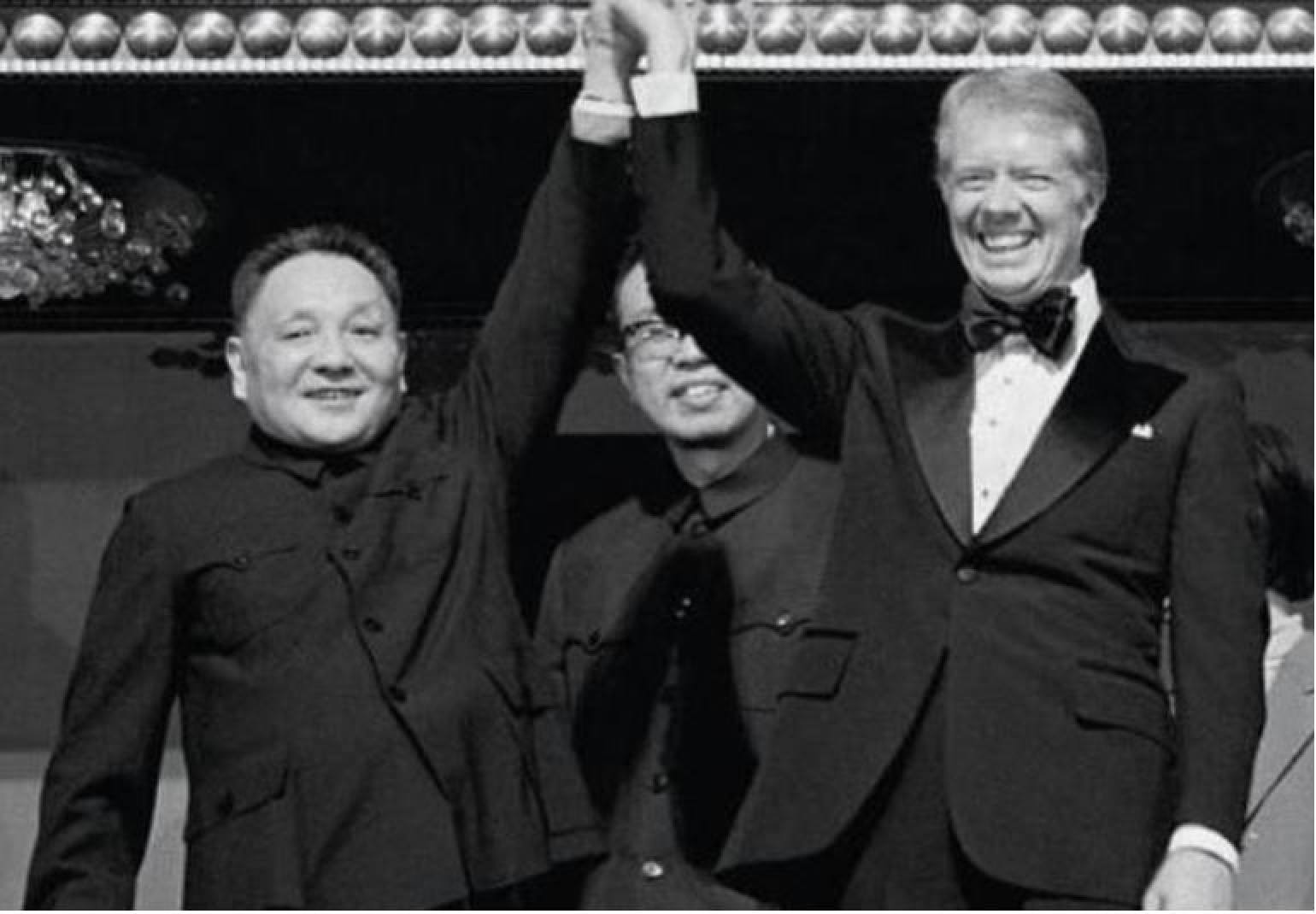

With the beginning of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms in China, a small revival of interest in their activities began. Linda Lim and Peter Gosling organised a major conference in 1980 at the University of Michigan to examine the complex relations of ethnicity, identity politics and economic activity. Three years later, my colleague Jennifer Cushman helped me organise another, focused on the theme of identity, at the Australian National University in Canberra. Another reason for the fresh interest was the success story of Singapore, where a majority Chinese population was building a special kind of nation after unexpectedly gaining its independence. Both meetings concentrated on Southeast Asia. Neither anticipated the wave of new migrations that began soon afterwards.

Growth of overseas Chinese

It was Wang Ling-chi who ventured the bold idea that the overseas Chinese were now a global topic of growing concern when he organised the 1992 conference in San Francisco. His call to look at the subject again stressed how the Chinese were not sojourners but immigrants.

It was time to move away from old stereotypes, to examine the new role that overseas Chinese were now playing and describe the differences this was making to received wisdom. After a dozen years of Deng Xiaoping reforms, China was changing rapidly from a revolutionary communist regime, to one that was adapting itself with notable success to a global market economy.

In retrospect, it was a confused world we faced in the early 1990s. On the one hand, the Chinese had crushed the 1989 Tiananmen activists and the world was uncertain about where China was going; on the other, the Cold War came to an end and we had to think about a world where there was only one superpower. It was a timely moment to consider the future of the overseas Chinese. That was also when new kinds of Chinese were moving out on a scale that matched the numbers last seen during the first decades of the century.

When Ling-chi called for that meeting, he was concerned to distinguish between those who had settled down and sunk roots in their adopted countries, and new departures who intended to be temporarily resident abroad and, ultimately, as in the past, return home to China. This reminds me to add that in Singapore, about this time, the same distinction was being emphasised when Chinese community leaders initiated a drive that led to the establishment of the Chinese Heritage Centre under Lynn Pan and, eventually, to the publication of her excellent Encyclopaedia of the Chinese Overseas in 1998.

Let me now turn to one of the results of the San Francisco conference, the formation of ISSCO. I am not sure if Ling-chi expected to see the subject change as fast as it did any more than I did. The people leaving China to live and work in the rest of the world from then on were extraordinarily varied. It was not only a question of numbers, but also how they represented a different kind of migration.

These were voluntary migrants who included large numbers with post-secondary education, people with high levels of professional skills, and who were adventurous people with capital and assets. It was also a time when the Chinese economy was undergoing a veritable revolution and changing at speeds no one predicted could happen. Who could have anticipated that China today would be the world’s number two economy? Now, people both within and outside see China as an alternate power to the United States.

I was astonished at the speed of China rising and of the West losing confidence

Of course, this is not entirely China’s doing. To a large measure, the United States contributed to that rate of growth and the emergence of this new perspective. In addition, no one expected the politics of the United States to make other leaders wonder if the country could continue to maintain the global leadership position that it enjoyed for so long. That was quite unexpected. It is not surprising when Chinese leaders now look to see what advantage they can gain from a condition where the United States seems less willing to lead the world.

I was astonished at the speed of China rising and of the West losing confidence. It is one thing to expect the dynamic economic centre to shift eventually from the Atlantic to the Indo-Pacific. It is quite another to hear the American president change his strategic focus from the Asia-Pacific to the idea of a “free and open Indo-Pacific”, a condition that was the norm for millennia before the expanding West undermined it with their powerful navies over 200 years ago.

To speak of the Indo-Pacific reminds us that the old world of maritime Afro-Eurasia has always been free and open. It also suggests that Chinese President Xi Jinping’s reference to a “new era” at the Communist Party’s 19th Party Congress may come from his perception of the changes that the world is going through and his hope that there could be some return to older norms.

The question relevant to us is how will all this affect the position of the overseas Chinese? Knowledge and understanding of these communities have attracted more attention during the last 25 years. We may claim that some of it can be attributed to the work of our ISSCO members.

But credit has also to be given to the many more institutions that now do research and publish on the subject. I do not know how many scholars have entered the field in the last 25 years, but clearly the field has expanded. Unlike 40 years ago, when the numbers were relatively small, many now venture forth to study a greatly expanded range of issues pertaining to the much larger numbers of communities.

From private lives, their families and their adjustment and adaptation problems, to the use of education for upward mobility, the way their children and other descendants respond to local civil life, the way they meet new and unexpected challenges, and how they now face a rising China, there is hardly any part of these overseas lives that are not being explored and explained. This is most encouraging, and we must commend all those dedicated to the field for their achievements.

New roles for overseas Chinese

Finally, I come back to the rise of China and the future. It does not matter much what overseas Chinese think about China. As China globalises, it will continue to have a greater impact on their lives wherever they may be. No matter how we look at China’s population or its economy, the renewal of a major civilisation is a process that we must respect.

The bottom line of China’s ambition is now clearer. The country will not be satisfied with being just another nation-state. Its peoples wish to shape their own distinctive culture and restore it to its old position, but this time, as both a multiplex state and a modern civilisation. Their search for modernity is now being done on its own terms. That may not be what everybody likes, nor even what the overseas Chinese would like to see. But it is going ahead anyway; it is big and ambitious, and now strong enough to map its own course.

I do not know what that will eventually look like but expect it to be part and parcel of what ISSCO and all those studying the overseas Chinese will have to take into account in their research. There is now little that the overseas Chinese do that can be totally free from the impact of a risen China.

When I was young, I saw news about China in the newspapers only once in a while. Today, in newspapers online or in print every day, there is likely to be a page or more that touches on what China does or does not do. This has happened in just my lifetime alone, and I find it an amazing turnaround. It is relevant to the role of the overseas Chinese and an organisation like ISSCO. How ISSCO members respond to the challenge to study the changes, and how they try to reassess what is known of the past and how that might help scholars think about the future, are questions that we cannot avoid.

I hope that the light we can throw on these issues can help the lives of people who come after us. These include people born and brought up overseas, and those who are leaving China now to live overseas. Like it or not, they will also have to learn to deal creatively with those in China who want all those overseas to be part of one big family of Chinese while they live abroad.

Excerpted from Roads to Chinese Modernity: Civilisation and National Culture by Wang Gungwu’, published by World Scientific Publishing.