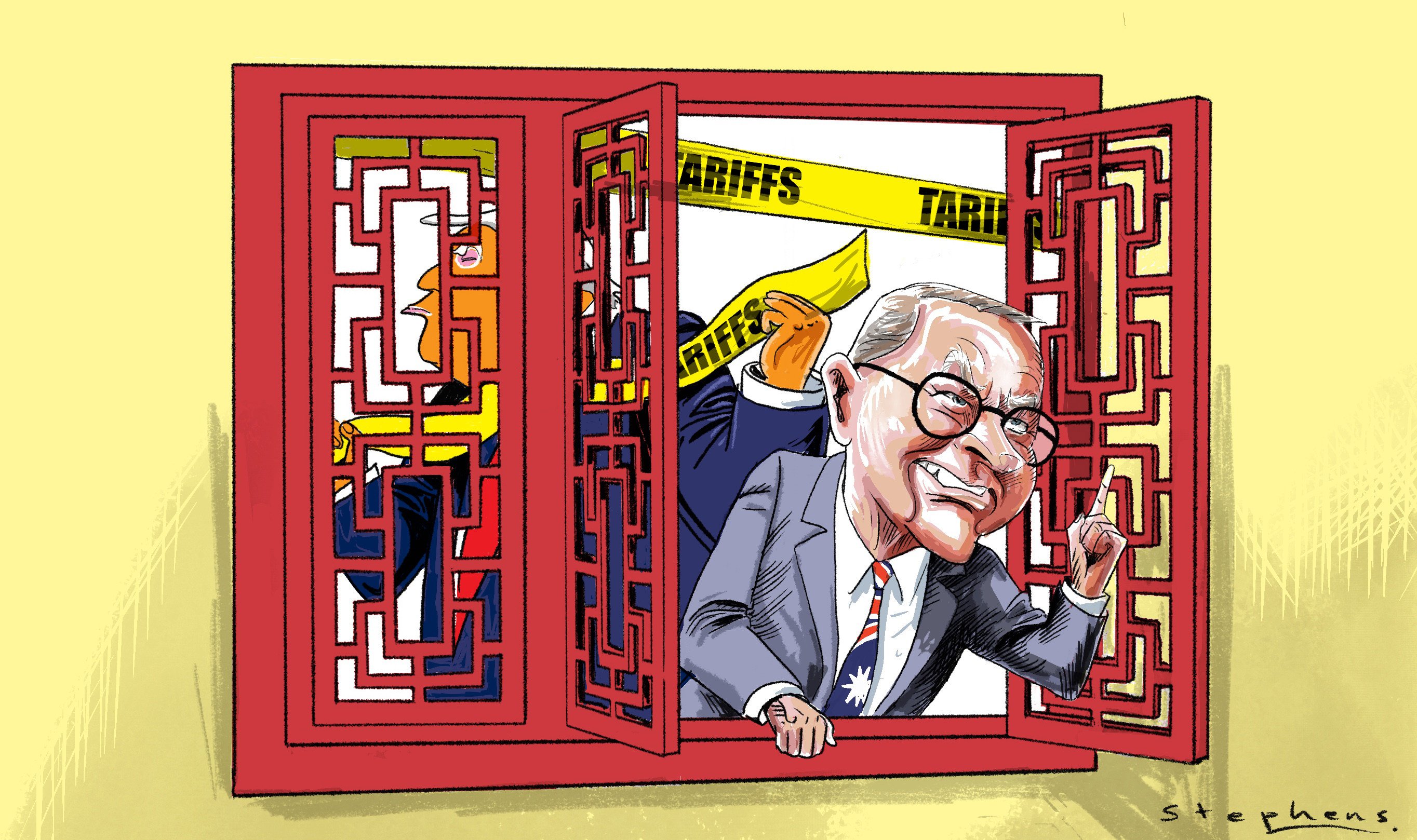

How Australia can use the Trump tariff pause to stabilise ties with China

A clear long-term strategy, reframed political narrative and revitalised people-to-people ties can help mend years of distrust and antagonism

Australia stands at a critical crossroads in its relationship with China. Recent news of Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s planned second official visit signals yet another step in stabilising the Australia-China relationship. The timing is notable: the 90-day pause in the US-China tariff war gives Australia the opportunity to pursue its own trade and diplomatic interests in a shifting regional landscape.

As a middle power with a small population and an export-driven economy, Australia has long managed a dual dependency with its security underpinned by the United States and its economic prosperity driven by China. In 2023, China bought more than A$219 billion (US$142 billion) worth of Australian exports, nearly one-third of Australia’s total global exports.

Relations have been fraught for much of the past decade. Tensions escalated after Australia’s 5G network ban of Huawei and ZTE and concerns over foreign interference. The relationship sharply deteriorated when then-prime minister Scott Morrison called for an independent inquiry into Covid-19, prompting Beijing to impose sweeping trade restrictions in retaliation.

Since taking power in 2022, the Albanese government has overseen a thaw in relations. The prime minister’s 2023 visit to Beijing marked a diplomatic reset, followed by Canberra’s suspension of two World Trade Organization cases against China. In late 2024, Beijing lifted its remaining trade restrictions on Australian goods.

At present, Canberra’s approach is framed as “cooperate where we can, disagree where we must”, but there are persistent differences, such as over the South China Sea and China’s expanding influence in the Pacific Islands. Concurrently, concerns about the reliability of an increasingly transactional US administration add urgency to Australia’s efforts to cultivate a stable, constructive relationship with China.

Against this backdrop, Australia has a strategic window to recalibrate its China policy. Despite ongoing challenges, there are three clear steps it can take to strengthen and future-proof bilateral ties.

First, Australia must develop a comprehensive, long-term China strategy that provides clarity and coherence across government and business sectors. Such a strategy would depoliticise sensitive issues, guide responses to external shocks and regional flashpoints and shift policymaking away from the current reactive, security-focused lens.

Clearly defining strategic objectives, red lines and sector-specific opportunities and constraints will reduce the risk of contradictory decisions. It will also signal to domestic and international stakeholders that Australia is pursuing an autonomous, interests-based approach, neither yielding to Chinese coercion nor uncritically following Washington’s lead.

Lessons can be drawn from existing frameworks such as the Southeast Asia Economic Strategy to 2040, which promotes sectoral cooperation, economic engagement and stronger people-to-people links between Australia and regional partners. A comparable China blueprint should likewise emphasise stronger economic engagement in key areas where cooperation is mutually beneficial – such as tourism, clean energy and education – as well as other non-contentious domains like multilateral peacekeeping.

Public concerns must be acknowledged. Public fears have been fuelled by recent incidents such as reported sonar injuries to Australian Navy divers in the South China Sea, Chinese naval activity near southern Australian waters and live-fire exercises in the Tasman Sea without adequate prior warning.

With only 17 per cent of Australians trusting China to act responsibly in the world and many viewing it as a future military threat, a national China strategy must address domestic expectations and national security risks. However, seeing China solely through a security lens distorts broader national interests by undermining Australia’s capacity to engage effectively.

Second, Canberra should reframe its political narrative on China and reinvest in informal diplomacy without defaulting to antagonism. While national security concerns such as foreign interference and critical infrastructure vulnerabilities have rightly informed policy, casting the relationship as a binary contest risks deepening mistrust and narrowing diplomatic space.

In areas of sharp disagreement – such as Australia’s participation in the Aukus grouping or its stance on the South China Sea – Canberra should clearly articulate its positions to reduce misinterpretation and avoid reinforcing zero-sum narratives that inflame tensions.

Concurrently, Australia should reinvigorate informal diplomatic channels, particularly Track 1.5 and Track 2 dialogues. These platforms allow for candid, off-the-record exchanges among officials, academics and experts, helping to clarify misunderstandings, build trust and prevent miscalculation on issues like regional security and technology competition. During periods of formal strain, such mechanisms become even more critical.

Third, Australia must revitalise people-to-people ties to build stronger “China literacy” and long-term trust. The fall in the number of Chinese students during the Covid-19 pandemic exposed the fragility of existing connections. Rebuilding these links through education, tourism and cultural exchange is essential to restoring mutual understanding, helping de-escalate tensions and also insulating bilateral ties from political volatility.

Academic exchanges are equally important. A 2023 report from the Australian Academy of the Humanities called “Australia’s China Knowledge Capability” warned of a decline in China studies across Australia, particularly in universities, and of a weakening ability to generate direct knowledge of China at a time when strategic understanding is more essential than ever.

To this end, expanding tertiary-level initiatives such as the New Colombo Plan and Westpac Asian Exchange Scholars can help reverse this trend. These programmes offer young Australians first-hand experience of China while also cultivating a new generation of China-literate leaders. Such exchanges are key to rebuilding trust and fostering deeper societal understanding.

Australia has a clear interest in keeping communication channels open and fostering a stable, constructive relationship. However, this is a two-way street as China also has a responsibility to engage seriously with these overtures.