How a scam network evolved after a nation-wide crackdown in the Philippines

Observers warn the Pogo industry’s replication in Pakistan is part of ‘a natural progression’ for illegal networks

A scheme to traffic Filipinos into Pakistan to work for gaming firms formerly based in the Philippines has exposed the latest evolution of online scam networks linked to the controversial Pogo industry, immigration officials and analysts warn.

The case – the first known incident involving Filipinos being trafficked to Pakistan – suggests that criminal syndicates previously operating under Philippine Offshore Gaming Operator (Pogo) licences are shifting to new jurisdictions following a government crackdown on the sector.

On July 6, four Filipinos bound for Hong Kong were intercepted at Manila’s Ninoy Aquino International Airport after immigration officers found discrepancies in their statements.

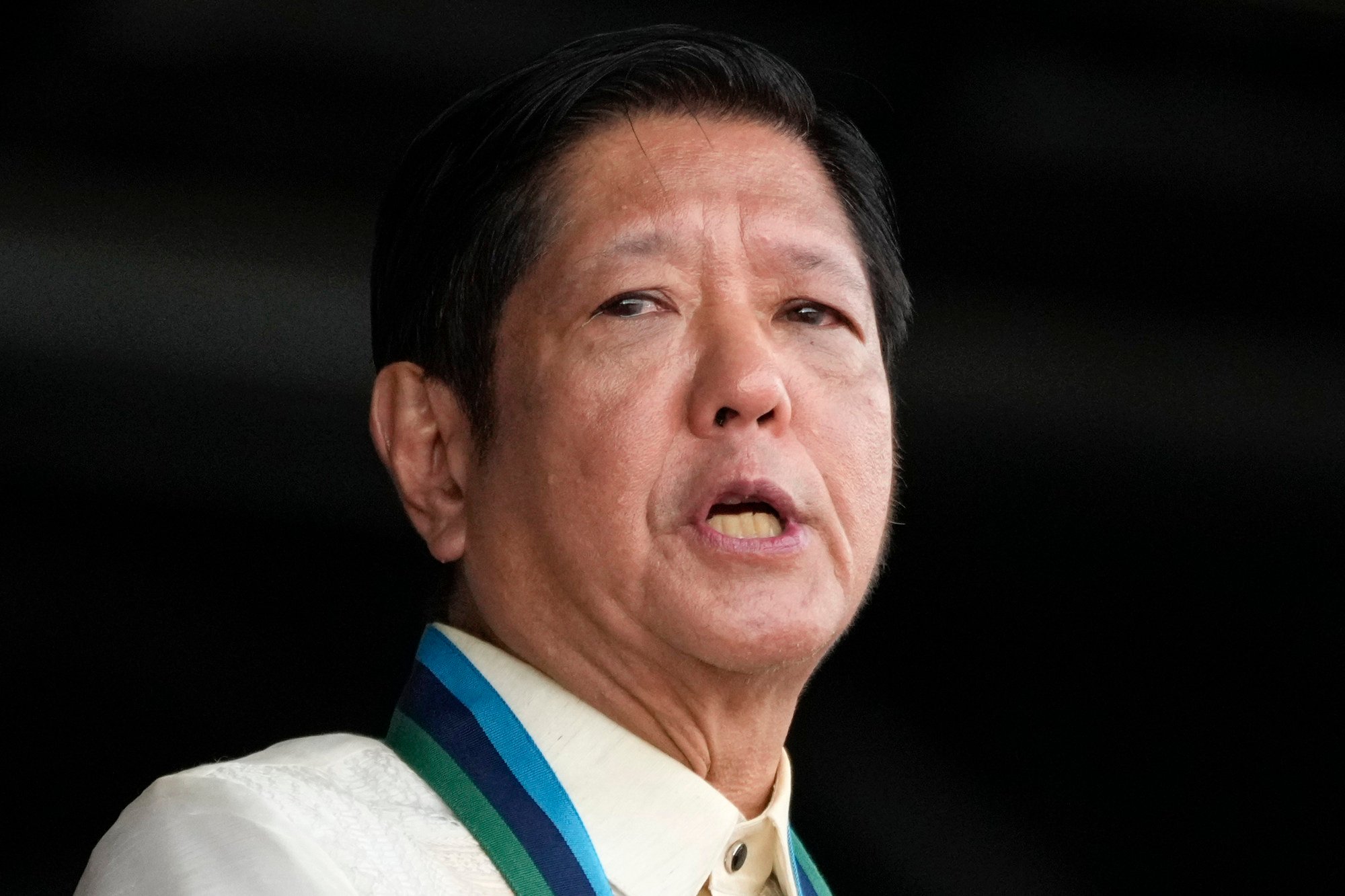

Investigators later discovered that their real destination was Pakistan – and that one of them, a former Pogo worker, had been recruited by a Chinese ex-employer who had relocated operations after President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr ordered a nationwide Pogo shutdown last year.

In October, the Marcos administration ordered foreign Pogo workers in the country to voluntarily downgrade their visas before 2025 or face deportation.

The four Filipinos intercepted at the airport last week were the “first confirmed case involving Pakistan”, Melvin Mabulac, the Bureau of Immigration’s deputy spokesman, confirmed in a television interview with ABS-CBN News last week.

“We have no record of other interceptions involving passengers going to Pakistan before this,” he said, but added that the bureau was now studying the possible use of multiple exit strategies deployed simultaneously to smuggle Filipino workers out of the country.

These include booking flights masked as legitimate tourist trips or exiting through back-door areas in southern Philippines – likely a similar route allegedly taken by fugitive former mayor Alice Guo, who was suspected of being a Chinese asset at the height of Senate hearings on linked criminal activities to Pogos.

“When we are very strict at the airport, they usually go to the back door in the south,” Mabulac said.

Areas such as Palawan, Zamboanga and Tawi-Tawi were popular trafficking exit points, Mabulac noted, adding that many Filipinos rescued by authorities in trafficking schemes abroad never left through airports.

The Pakistan case mirrors the schemes operated by trafficking syndicates in Cambodia, Myanmar and Thailand, according to Mabulac.

“We are looking into the possible new destinations of those being victimised, now transferring to Pakistan,” he said.

The Bureau of Immigration had continued recording cases of Filipinos being trafficked to Myanmar and Cambodia, Mabulac said, but did not share specific figures.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

Mabulac warned that traffickers had become quick to respond to recent enforcement measures, noticing a rise in counterfeit travel documents to exit the country, but said immigration officers were able to intercept them.

Evolving Pogo operations

The recent trafficking incident is likely an offshoot of the scam operations associated with Pogos, especially at the height of the pandemic, according to analysts.

Alexander Ramos, a former undersecretary and executive director of the Cybercrime Investigation and Coordinating Centre, told This Week in Asia that criminal syndicates likely took advantage of the legitimate franchises that Pogo firms held, as well as the infrastructure that could house these operations during the lockdown.

“Historically, we know that there are criminal syndicates operating within that industry. What happened was they shifted their businesses to continuously survive … They were running illegal operations within the protections and confines of their licence,” Ramos said.

“This is an evolution of fraud operations dating back to the 2000s.”

Ramos, who has been investigating transnational crime since the 1990s, said these operations had long been entrenched in the Philippines even before the Duterte administration, when more than 300 Pogos operated in the country and revenues peaked at 6.6 billion Philippine pesos (US$116.4 million) in 2018.

The industry snowballed from unregulated online casinos catering to overseas clients and operating in special economic zones to the parallel rise in syndicated operations of scams run in the Philippines targeting China-based victims between 2003 and 2008.

By 2010, there was a steady growth of Chinese-run online gaming companies operating in special economic zones. During Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency in 2016, the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation began regulating these operators and issuing their licences, leading to billions in annual revenue for the agency.

Following Marcos’ ban on Pogos in 2024, more than 9,000 Pogo workers remain at large in the country, while 500 are in custody and await deportation at a detention facility in Pasay City.

Ramos said he had reason to believe that the trafficking schemes recorded in Myanmar, Cambodia and Thailand, as well as in Pakistan, were related to the now-banned Pogo industry.

“It’s easier for them to put up their operations overseas at this point. We’re seeing that this could boom in South Asia and Africa, as their systems have not been widely exploited yet,” he said, adding that India’s size could pose a challenge in tracking and tracing these activities.

Jan Chavez-Arceo, a national security fellow of the Philippine Council for Foreign Relations, said Filipinos had become a target of the recent human-trafficking operations “because these transnational criminal organisations understand very well the vulnerabilities and desperation of Filipinos to look for economic opportunities they feel are not available to them in the Philippines”.

Several cultural similarities made it easier to “integrate Filipinos with South Asians in these Pogo operations”, Chavez-Arceo said, noting that the replication of the Pogo industry to Pakistan was “a natural progression” for illegal networks to operate in a more conducive location.

Chavez-Arceo stressed that the Philippine government should provide more economic opportunities for Filipinos and “exact more stringent deliverables” from law enforcement agencies “to ensure that any complicity by any government personnel will be meted out with more severe penalties”.

“For as long as there are highly vulnerable Filipinos who feel desperate and marginalised in their own country, there will always be predatory criminals who will victimise our countrymen for their evil schemes and illegal operations,” she said.

Ramos stressed that the country had overlooked the plight of thousands of Filipinos displaced by the closure of Pogos, who had lost their livelihoods and needed to transition their skill sets for legitimate opportunities.

“How do you transition those skill sets? We did not prepare adequately for this. How do we transition them into legitimate work? Did we produce or did we find a market for them so they don’t feel disadvantaged here in the Philippines?” he said.

The lack of opportunities had led to a rise in “guerilla scam operations” run by Filipinos, he noted.

“Why? It’s simple. As long as you have a cellphone, a computer and the AI tools, it’s so easy to hide and deceive. You don’t have to go out. And you can keep your revenues all to yourself,” he said.

Chavez-Arceo warned that Filipinos would remain prone to victimisation by human traffickers as long as high-ranking officials and leaders “perpetuate a culture of corruption and self-interest”.

She called on the Philippines to step up enforcement and leverage multilateral mechanisms such as the Asean Convention Against Trafficking in Persons, and complete the drafting of a regional cybercrime convention that would effectively counter cybercrimes and foster cross-border cooperation in the region.