‘Did we really win?’: Bangladeshis weigh progress a year after uprising

Momentum for reform has been stymied by a hostile bureaucracy and political fragmentation, as disillusionment grows on the streets

A year after the autocrat Sheikh Hasina was toppled, Habibur Rahman still carries the physical scars of Bangladesh’s revolution – he walks with a limp and says the birdshot lodged in his skull sometimes pulses like a warning.

But it is his right eye – sightless, unmoving and faintly crimson – that tells the real story of those bloody, chaotic days.

On July 18, 2024, riot police opened fire on demonstrators in Dhaka’s Jatrabari neighbourhood, on Hasina’s orders.

Students had taken to the streets after several unarmed classmates were killed protesting against a rigged public service job quota system. Habibur, then 24, was near the front line and never saw police open fire with shotguns. The pellets tore through his face, neck and shoulder.

Now he will never again see from his eye.

Habibur – who also goes by Habib – still keeps the blood-soaked shirt he wore that day folded in a drawer he rarely opens, a painful, hidden memory of the moment student protests erupted into a national revolt that ultimately ousted a dictator.

But he is alive, unlike 1,400 others who UN investigators say died in the ensuing crackdown.

“We paid the price to bring the dictatorship down,” Habib says. “Now we’re trying to earn what comes next.”

Garment workers walked off factory floors. Teachers abandoned classrooms. Rickshaw pullers and vendors poured into the streets.

Three weeks later on August 5, Hasina – Bangladesh’s longest-serving prime minister – was gone, fleeing her palatial Dhaka residence by helicopter as jubilant protesters looted her extravagant home.

That ended 15 years of increasingly iron-fisted rule and left her Awami League allies, once cross-stitched throughout the nation, suddenly in tatters.

Hasina is being tried in absentia for crimes against humanity at the country’s International Criminal Tribunal. Family members and cronies linked to her regime are being chased by Bangladeshi authorities through Interpol requests to the United Kingdom, Canada and the United Arab Emirates.

The 77-year-old is believed to be in hiding in India and has ignored repeated calls to return, instead lashing out from the sidelines with threats to “avenge the deaths” of Awami League loyalists and warning the Yunus administration that a reckoning will come.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

But there appears little near-term chance of her coming back – certainly as leader.

“She built a fascist system that didn’t just silence people – it erased their futures,” Habib told This Week in Asia. “We rose up to end that.”

Reform, resisted

The big promise of national renewal followed Hasina’s demise.

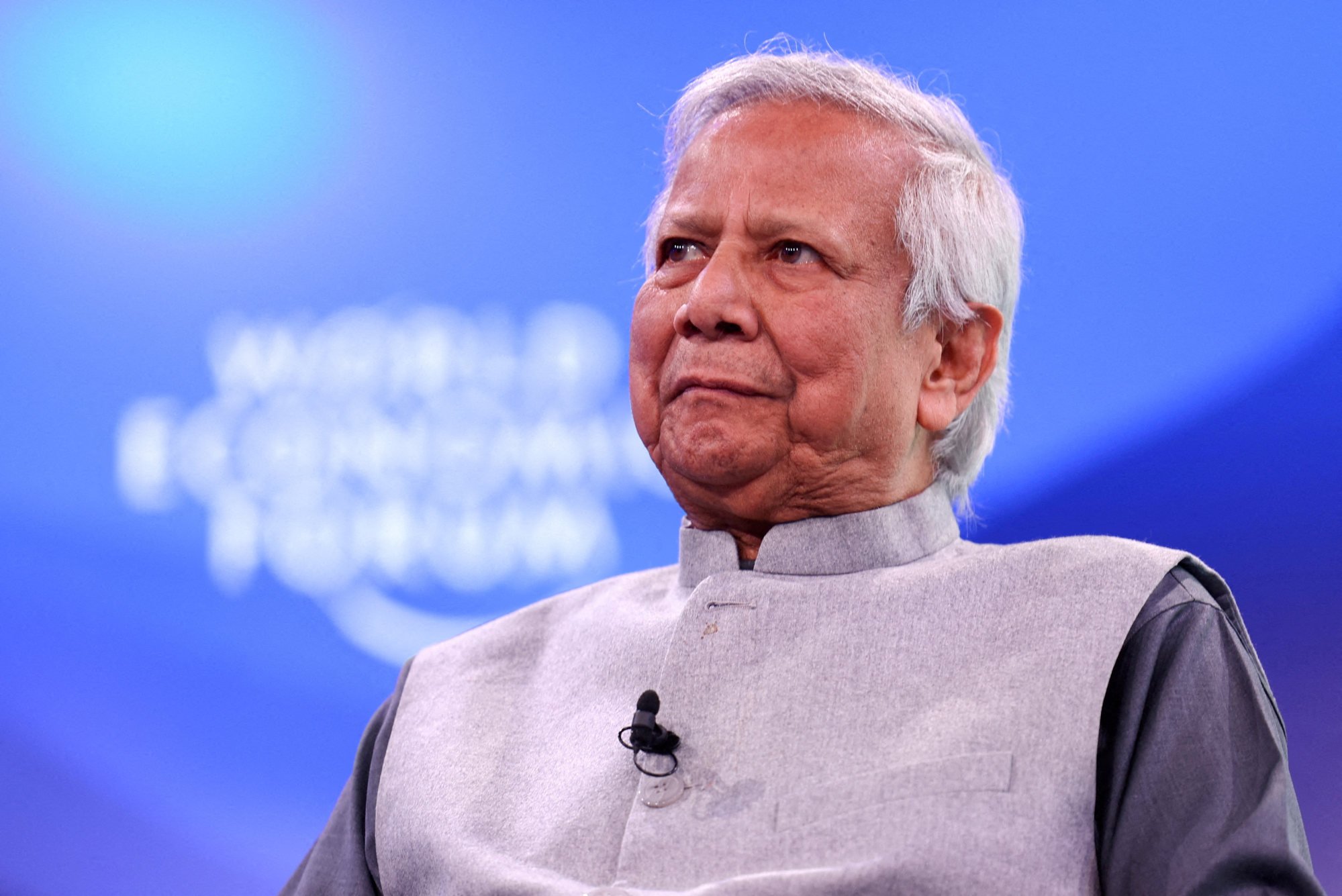

A coalition of student leaders, civil society groups and opposition parties filled the power vacuum and nominated Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus as interim head of state, a figure seen as both credible abroad and calming at home.

But a year on, Yunus is finding it hard to deliver on expectations that flowered in those early euphoric post-Hasina days.

Now 85, Yunus took on a Herculean task. He has pledged to overhaul the entire state machinery that had enabled endemic corruption, rigged elections and unchecked executive power.

Sweeping reforms are under way to rebuild an independent judiciary, a new electoral framework, decentralise power, clean up banks swindled by tycoons and recover billions of dollars siphoned abroad during the Hasina years.

Bangladesh, he said in his first address, would be “a new republic born on the ashes of repression”.

In his credit column, Yunus has repealed a slew of draconian laws, eased controls on the media, and opened political space for dissent.

His administration has launched expert-led committees to overhaul electoral systems, decentralise power, and root out corruption.

Abroad, Yunus has sought to recalibrate Bangladesh’s strategic posture – seeking relief from US tariffs and leverage with India, the interim government turned to China, securing US$2.1 billion in pledges during Yunus’ March visit to Beijing.

But momentum has stalled. Inflation remains stubbornly above 9 per cent. Youth unemployment is high. And Yunus’ ambitious agenda is bogged down by a hostile bureaucracy, political fragmentation, impatience and now the storm clouds of tariffs from Washington which menace Bangladesh’s export-reliant economy.

Meanwhile, old regime loyalists across the bureaucracy are quietly undermining reform efforts, government insiders say, by delaying procurement, withholding data and stalling proposals in committee.

“They know the system better than anyone,” a senior aide to Yunus told This Week in Asia, requesting anonymity. “They’re just waiting us out.”

Political allies have also grown wary, particularly over constitutional changes that could weaken their future standing, while powerful business families tied to the financial sector have pushed back against attempts to strengthen the central bank and enforce anti-money-laundering measures.

“We had everything, a solid plan and a clear vision,” the aide added. “At every step, we’re up against the ghost of the government we thought we’d buried.”

Hope diluted, but not gone

Some student leaders have accepted roles in the interim government, embracing the gradual, complicated nature of reform. Others accuse them of selling out.

“We didn’t fight just to change faces – we fought to change the system,” says Umama Fatema, 27, a former protest coordinator. “What I fear now is more of the same.”

That disillusionment echoes on the streets. “I thought we were starting something new,” says Shaheena Begum, a garment worker from Savar who joined the protests after watching students gunned down live on Facebook. “But prices are still high, factory owners still cheat us, and the powerful are bickering again. Did we really win?”

To bind the cracks, the interim government launched the National Consensus Commission in February to build agreement around key reform proposals from the 11 expert committees formed under Yunus’ leadership last year.

Chaired by Yunus, it brought together more than 30 parties to draft a “July Charter” for elections slated for as early as February next year and reform.

But rifts remain over major constitutional changes – whether to rewrite it entirely or amend key provisions – and how far to limit executive power.

One group trying to break the deadlock is the National Citizen Party (NCP). Born from the protest movement, it pitches itself as the uprising’s political heir and champions transparency, digital rights and inclusive development.

The NCP says the new charter should have a “Legal Framework Order” to ensure no future government can dismantle its reforms. It is about “fundamental change”, says senior NCP figure Akhtar Hossain. “We won’t survive if we get bogged down in endless debate.”

But as Bangladesh regroups after Hasina’s fall, a dangerous force is re-emerging: hardline Islamist groups. Long suppressed under the former regime, they are organising mass rallies, tapping up rural strongholds and shaping public discourse through mosques and madrasas.

Their influence – of groups like Hefazat-e-Islam – has stalled legislation to ensure equal inheritance for women and protect against forced religious conversion. LGBTQ rights, always contentious in a Muslim nation, have again become easy targets for vitriolic sermons and protests.

“Right after August 5, it felt like we had achieved something profound,” says Nadira Yeasmin, a professor, feminist editor, and outspoken advocate for secular values.

“It felt like the old demons were gone. But what shocked me was how quickly even the new administration softened in the face of pressure from those who want to curtail women’s and minority rights.”

After voicing support for inheritance equality and defending the women’s reform agenda, Nadira was branded a blasphemer.

In May this year, Hefazat issued a 48-hour ultimatum for her removal as a professor of Bangla language at Narsingi Government College. The government responded swiftly – reassigning her to a remote conservative district and subsequently stripping her of teaching duties.

“I found almost no one in government willing to stand up for me,” she told This Week in Asia. “I was on the front lines of last year’s protests. Is this really what we fought for?”

Justice and real change

Yet, something fundamental has shifted. Bangladeshis are no longer afraid of politics and speak, debate and organise openly without fear of jail.

New political formations – like the NCP led by young activists, labour organisers and technocrats are taking root, while the old guard, including the Awami League, remains deeply discredited.

The main obstacle to moving forward is justice, many say.

Prosecutors have spent months compiling evidence of extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and a brutal crackdown on student protesters that culminated in Hasina’s fall. But so far, no state officials have been successfully prosecuted for the deadly crackdown last July.

Hasina’s party has dismissed the allegations as politically motivated.

For survivors of the uprising, the road to healing runs through the courtroom.

“My brothers didn’t take the bullets just to change who sits in the chair,” Habib says. “We want justice. We want Hasina – and her killers – held to account.”