Crisis calculations: Trump’s America leaves Southeast Asia in a spin

Punitive tariffs and severe aid cuts are shaking the foundations of the US relationship with Asean, deepening a sense of ‘unreliability’

Five months into Donald Trump’s presidency, Southeast Asia finds itself adrift. The foundations of its relationship with the US have been shaken by punitive tariffs and a sudden withdrawal of aid that hurt some of the region’s most vulnerable – even as Washington maintains its military presence with an eye fixed squarely on China.

This volatility has deepened a sense of American “unreliability” across Southeast Asia, according to experts who spoke to This Week in Asia.

Yet a complete rupture between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the United States remains unlikely. With China looming large across the horizon, Washington’s security commitments are expected to endure and continue shaping the region’s diplomatic calculus.

At the recent Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth laid out Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategic vision, citing Beijing’s relentless military drills around Taiwan and escalating naval confrontations in the South China Sea.

“There’s no reason to sugar-coat it,” Hegseth said. “The threat China poses is real, and it could be imminent.”

Hegseth called on US allies and partners to share more of the defence burden, stressing that such cooperation would enable Washington to allocate more resources to the Indo-Pacific, describing it as “our priority theatre”.

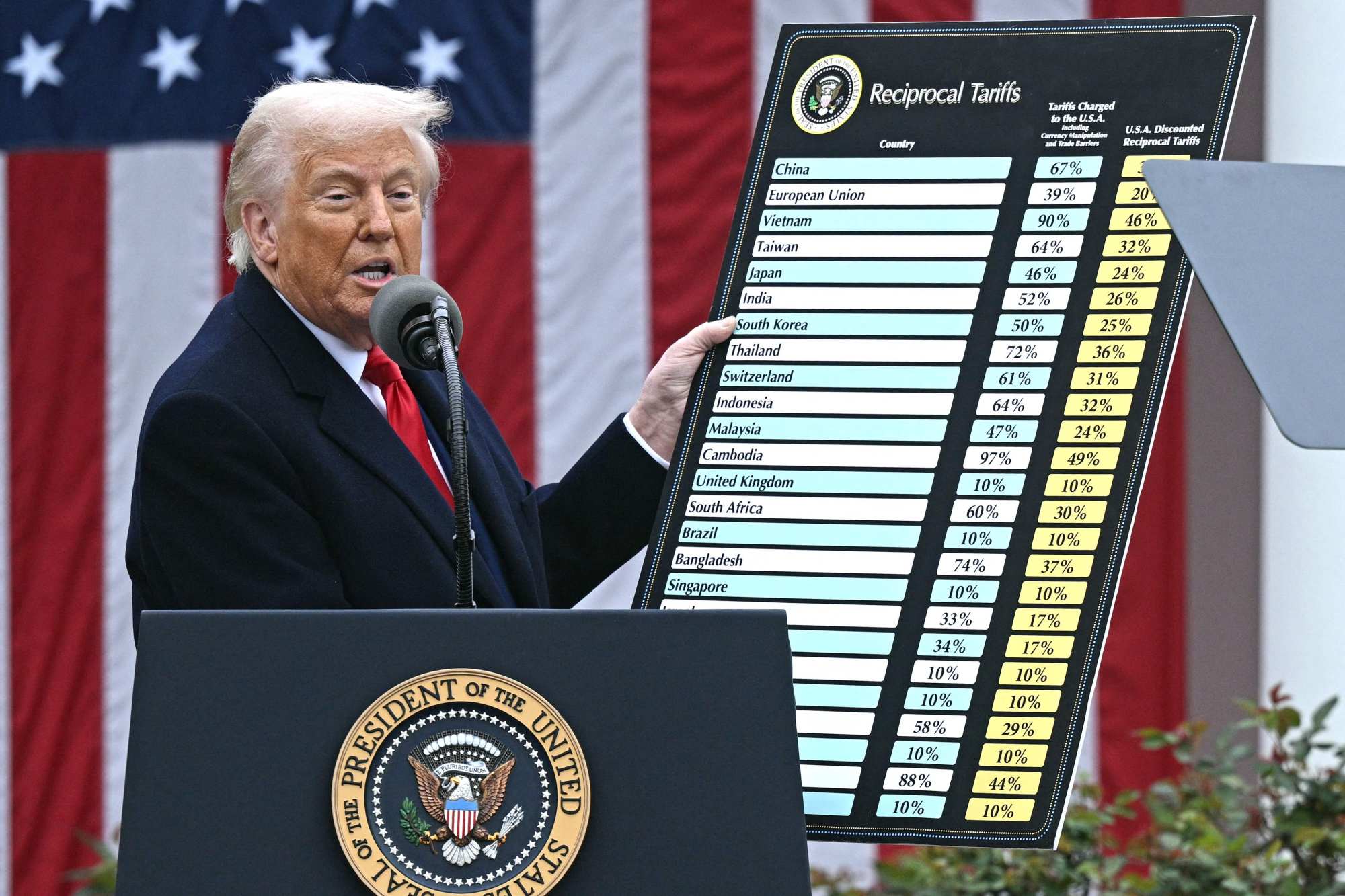

But Southeast Asia is also a priority for US commerce officials: in April, Trump announced sweeping “reciprocal” tariffs – ranging from 10 to 49 per cent – on Asean’s export-reliant economies.

Meanwhile, brutal cuts to US foreign aid have left a deep mark on the region, abruptly terminating long-term projects in healthcare, demining, support for civil society and other programmes.

Not only that, the Trump administration’s ban on foreign citizens from 19 countries entering the US, which took effect on June 9, included nationals of Myanmar and Laos.

Brandishing the threat of tariffs, Washington also reportedly sought to discourage governments worldwide from attending a UN conference this week on a possible two-state solution to the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, according to a US cable seen by Reuters.

America’s tariffs, erratic policymaking and stance on the Middle East “have certainly strengthened a perception in Asean of Washington’s unreliability,” said Sarang Shidore, director of the Global South programme at the Quincy Institute, a Washington-based think tank.

“In the shorter term, Asean states will do all they can to limit the damage,” Shidore said. “Offering concessions on trade and their approach on the Middle East has not gone beyond diplomatic criticism of US actions,” he added, noting that on security, Washington was thus far “staying the course” against China.

But in the longer term, Shidore warned that US unreliability would accelerate “structural drivers for diversification” – a protracted process for those economies most reliant on US markets.

This week, the Philippine army said it would welcome more US Typhon missile systems to expedite troop training and strengthen deterrence. The ground-based launcher, capable of firing Tomahawk and SM-6 missiles up to 2,000km (1,240 miles), puts swathes of the South China Sea, Taiwan Strait and even the south of mainland China within range.

The first Typhon system arrived in the Philippines last year during joint exercises with the US – its first overseas deployment – and remains in northern Luzon for ongoing training.

But even when it comes to security, Shidore said countries like the Philippines had incentives to eventually seek a “more even-keeled policy” between China and the US.

“If there is any region in the world that has a good shot at reducing its dependence on the US, it is Southeast Asia, and current conditions incentivise it to make major efforts in that direction,” he said.

Trump’s tariff threats have not only forced Asean governments to rethink their trade with the US, but also reassess how they can secure longer-term growth as supply chains are thrown into chaos.

Yet despite these added strains, analysts say rash diplomatic moves are unlikely.

“I do not see the development of an outright rift between Asean and the US or, for that matter, US influence in the region eroding rapidly,” said Felix Chang, a senior fellow at the US-based Foreign Policy Research Institute think tank.

Southeast Asian nations have a long history of pragmatic diplomacy, and many still view Washington as essential for regional stability, economic growth and security – a relationship Chang says is resilient enough to endure.

“Despite policy shifts from Washington, Asean countries understand the US’ strategic importance and will continue to engage with it,” he added.

Money talks?

Asean remains one of America’s largest trading partners – total US goods trade with the bloc stood at US$476.8 billion last year. Washington is also a major investor in the region, especially in technology, energy and manufacturing.

“Ultimately, many Asean countries still greatly benefit from the US market, suggesting that economic interdependence will still play a crucial role in their relationships,” Chang said.

While the Trump administration is scaling back security commitments in Europe and the Middle East, US defence efforts in Asia are being reinforced, according to Chang, with allies including Japan, South Korea and the Philippines benefiting from enhanced deterrence capabilities.

The US Navy has stepped up freedom of navigation patrols in the South China Sea, and Washington has reiterated its commitment to a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific”.

“These should reassure America’s Asian allies that, in working to strengthen its regional military posture, that the US is actually more likely to come to their aid, if push came to shove,” Chang said.

Washington also remains deeply engaged in security partnerships with Asean, particularly through the Asean Defence Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM-Plus) and joint military exercises, including those with the Philippines and Thailand.

Hunter Marston, a researcher at Australian National University’s Southeast Asia Institute, said allies and partners were taking the Trump administration’s unpredictability “in stride”. Some, like the Philippines, were doubling down on their reliance on US security guarantees, he said, while others were broadening their network of strategic partnerships – including closer ties with the EU, Canada, Japan and Australia.

Malaysia, the current Asean chair, is among those looking to China. Trade Minister Tengku Zafrul Abdul Aziz spoke to Chinese Commerce Minister Wang Wentao in April, seeking deeper cooperation between Beijing and the bloc.

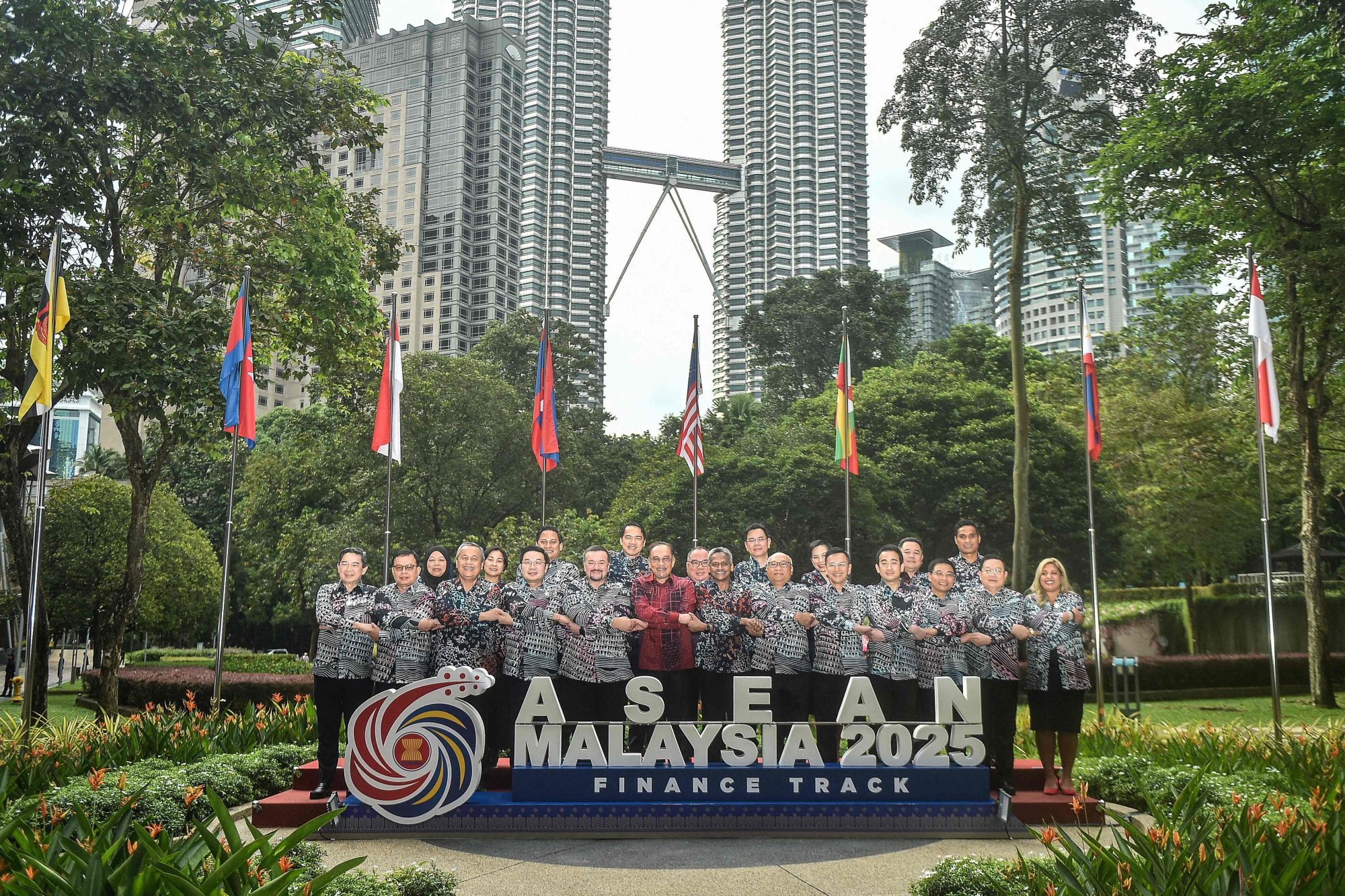

At last month’s Asean Summit in Kuala Lumpur, calls grew for greater regional integration and resilience against global trade disruption. “All this is to say that the current trend has already factored in US unreliability,” Marston said. “The Trump administration has not sparked any new form of hedging behaviour above and beyond pre-existing fears of US neglect or volatility.”

Marston pointed to the risks of a widening gap between US rhetoric and policy action, noting that Southeast Asia had long viewed Washington as “inattentive and inconsistent”. The Philippines, for instance, would continue to “oscillate” its China policy to best serve its own security, he said.

That includes Manila’s recent reciprocal access agreement for defence cooperation with Japan, atop existing arrangements with the US and Australia.

“I would expect Manila’s on-again-off-again tensions with Beijing to continue to drive friction in the relationship, particularly concerning disputed territory in the South China Sea,” Marston said.

Hanh Nguyen, a research fellow at the Yokosuka Council on Asia Pacific Studies who specialises in Southeast Asia’s international relations, said that despite the “bombastic rhetoric”, Hegseth’s speech had sought to reassure a region increasingly alarmed by China’s rising military power.

Those reassurances included a commitment to remain in the region and to strengthen military deterrence – moves consistent with previous US administrations, Hanh said.

But she described Hegseth’s promise of American staying power, while also following orders from Trump, as “contradictory”.

The heavy-handed reliance on military power while dismantling economic and soft power is not the region’s preference for US engagementHanh Nguyen, international relations researcher

“The heavy-handed reliance on military power while dismantling economic and soft power is not the region’s preference for US engagement,” she added.

During his first term in 2017, Trump withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, ending American participation in the 12-nation trade pact aimed at lowering tariffs and creating a free trade area.

In the vacuum, Southeast Asian nations have increasingly hitched their economic fortunes to China.

But this presents a dilemma for the Philippines, in particular: caught between US demands for greater defence spending and hosting more American troops, and the economic necessity of working more closely with China.

Lucio Blanco Pitlo III, a research fellow at the Asia Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation, argued that the US must do more than “lecture” about China’s economic influence.

“[Washington] has to offer robust alternatives to meet the region’s demand for greater access to export markets, infrastructure funding, and investment and technology transfer for industrial upgrading,” Pitlo said.

For example, he said the US should create more opportunities for allies and partners to develop their own defence industries.

“Beyond low-value ship repair, arms co-production and investment in allies’ shipyards should be considered,” Pitlo said.

Time ticking away

Trump’s tariffs, announced on April 2, were subsequently paused for 90 days, giving economies such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand a brief window to negotiate.

Whether Trump will follow through with his threats against economies that fail to open up to US investment or reduce trade deficits remains uncertain, but Asean’s has already got the message: new trading partners are needed.

Malaysia, for example, has pivoted more towards China in the wake of US tariff threats and Europe’s phase-out of palm oil exports.

Still, Asean as a whole has yet to adopt a unified position on the trade turmoil.

Indonesia, for its part, continues to advocate for stronger ties with the US, even as it deepens economic links with China, particularly in mining and minerals.

In April, Jakarta and Washington reaffirmed their commitment to expanding their strategic partnership in politics, security, trade and investment during a meeting between Indonesian Foreign Minister Sugiono and US Secretary of State Marco Rubio in Washington.

“So despite the disruptions under the early Trump administration, I believe Asean is unlikely to fully pivot away from the US,” Chang said.

“Instead, the region’s countries will likely maintain their divided preferences, leaning somewhat less toward the US, but not decisively turning its back on it.”

Still, Washington would be wise not to assume its old alliances are unbreakable, observers say, particularly as public sentiment in Southeast Asia sours over the White House’s heavy-handed tactics and the binary choice it offers between the US and China.

An ISEAS-Yusof Ishak survey this year found that 47.7 per cent of respondents across 11 Southeast Asian nations would choose China over the US if forced to align with one power.

Many Asean states will also seek to integrate more deeply with each other, and multi-align outside the region even moreSarang Shidore, geopolitical risk analyst

“Many Asean states will also seek to integrate more deeply with each other, and multi-align outside the region even more,” said Shidore of the Quincy Institute. “These preferences are deep-rooted and the larger and more capable Asean states have the means to make progress in that direction.”

Last month, leaders from Asean, the Gulf Cooperation Council and China convened in Kuala Lumpur for an inaugural summit to deepen cooperation in trade, supply chains, infrastructure and finance.

Meanwhile, Indonesia became the 10th full member of the China-led Brics group of developing economies in January, and Vietnam gained admission as a partner this month, joining Malaysia and Thailand.

“The unpredictability of both Washington’s policies and the US-China relationship will incentivise the region to seek insurance policies through enhanced multi-alignment and greater regional integration,” Shidore added.

Chang, meanwhile, recalled repeated warnings from Asean members, including long-time partner Singapore, advising the US not to force the region to choose between America and China.