China ‘has a lot of trust building to do’ in South China Sea, Philippines says

Manila’s defence chief says he wants China to engage in good faith. But observers note that trust is a two-way street

The Philippines’ defence chief has called on Beijing to engage in good-faith negotiations over the South China Sea, stressing that China still has a long way to go to earn Manila’s trust.

Observers warn that trust goes both ways, however, pointing to factors such as growing cooperation between Manila and Washington, and the reduced Chinese presence at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore over the weekend.

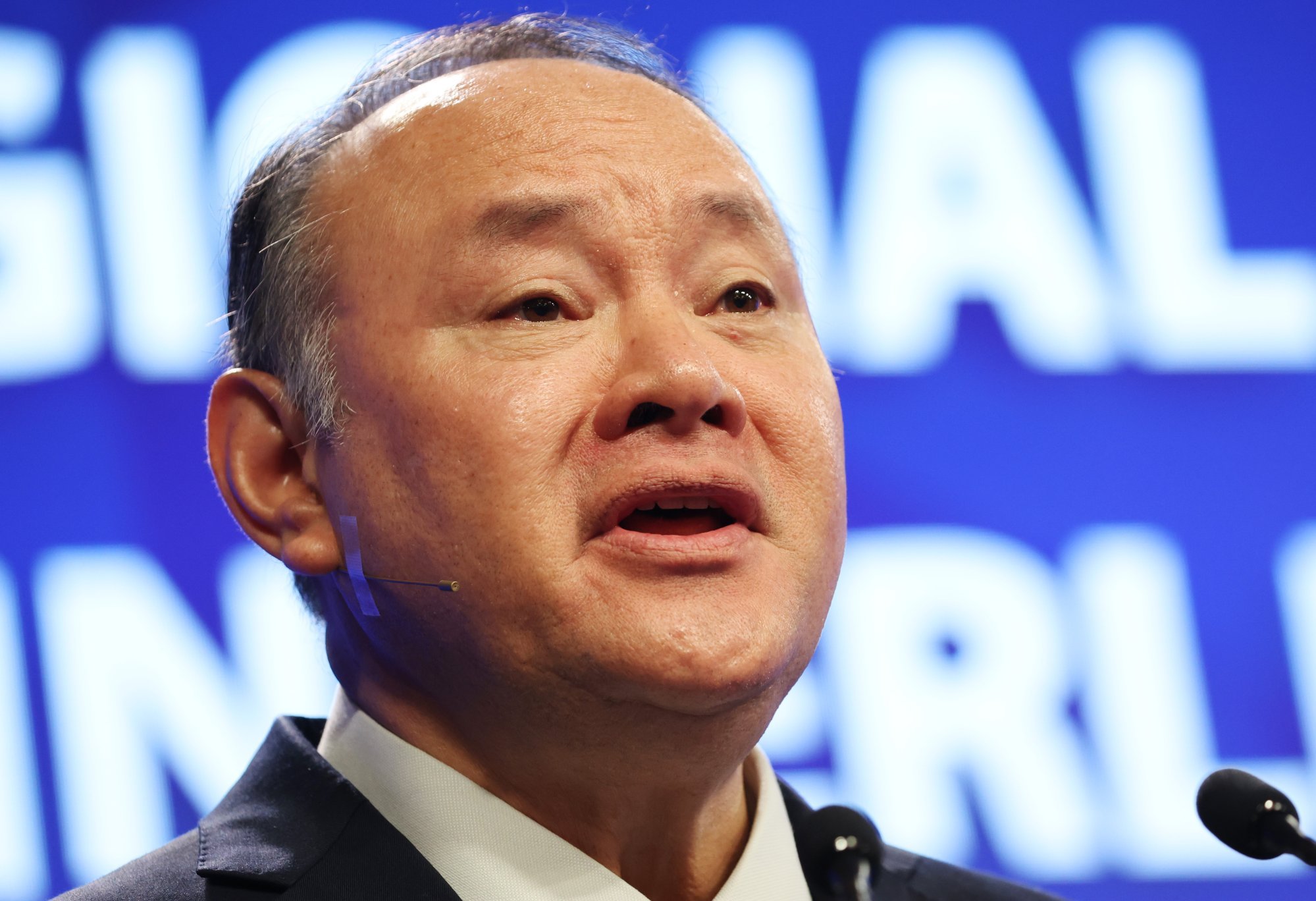

At the security summit, Philippine Defence Secretary Gilberto Teodoro Jnr rebuked a Chinese delegate who raised the issue of South China Sea tensions.

Senior Colonel Chi Zhang, had asked Teodoro whether Manila was concerned about a proxy war in Asia, citing the United States increasing arms sales to the region and establishing more military bases in the Philippines.

“Thank you for the propaganda spiels disguised as questions,” Teodoro said in response.

He then gave an example that he said proved China’s word could not be trusted.

“I just look back to 1995 on a place called Mischief Reef. There were a few bamboo structures erected there, and China said that these were temporary havens for fisher folk. Now you have an artificial military island, heavily militarised,” he said.

“China says it has peaceful intentions. Why does it continue to deny the Philippines its rightful provenance? And as proof of this, we do not stand alone. None have agreed with China and none have condemned the Philippines for standing up against China in the face of a threat to its territorial integrity and sovereignty.”

About 250km (155 miles) from the Philippines’ Palawan Island, Mischief Reef is a coral atoll in the disputed Spratly Islands. It has been under China’s control since 1995 and hosts a military base.

Manila and Beijing have been locked in a territorial dispute in the South China Sea, involving an escalating war of words and several naval skirmishes including vessel blockades and the use of water cannons.

In 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled in favour of the Philippines in parts of the disputed waters. But the court does not have the power of enforcement.

According to Teodoro, trust is necessary for dialogue to be effective. “China has a lot of trust building to do,” he said.

“To be an effective negotiating partner in dispute settlement, we have to call a spade a spade. And that’s what we see. And that is the biggest stumbling block to dispute resolution or dialogue with China.”

Trust is a two-way street

Observers said Teodoro’s remarks resonated with a growing number of Filipinos who were becoming increasingly aware of the legal and security dimensions of the row.

Danielito Jimenez, founder of advocacy platform The Pinoy Street Lawyer Official, said he found Teodoro’s position to be firm yet appropriately diplomatic.

Teodoro’s response to the Mischief Reef issue, the lawyer said, was “not merely a personal opinion, but one that should reflect the broader stance of the current president, who is constitutionally mandated as the chief architect of Philippine foreign policy”.

Laying the issue out as a “betrayal of trust” was a compelling narrative that would likely provoke a strong pushback from China.

“However, it is in China’s own interest to respond not with dismissiveness but with clarity and specificity about how it intends to resolve these long-standing and multilayered disputes,” Jimenez said.

Political analyst Sylwia Monika Gorska argued that trust was a two-way street, pointing to Manila’s expanding cooperation with the US under the Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement (EDCA).

In 2023, Manila gave the US access to four new military sites, on top of an existing five under the EDCA, which allows Washington to rotate troops and preposition defence material, equipment and supplies in specific locations around the Philippines.

The following year, Washington deployed the Typhon missile system, which can fire projectiles up to 2,500km (1,550 miles) – putting the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait within their range.

In April, the US also deployed an anti-ship missile launcher, known as the Navy Marine Expeditionary Ship Interdiction System, in Batanes near Taiwan. Beijing considers the self-ruled island part of China to be reunified by force if necessary. The US and other countries are opposed this, but do not recognise Taiwan as an independent state.

Manila describes its alliance with the US as a defensive deterrent. But Gorska said Chinese policymakers perceived it as part of a broader US-led containment effort.

“The situation reflects a dynamic security dilemma: defensive measures by one side generate insecurity in the other,” she said. “If Manila seeks genuine de-escalation, it must balance its alliance signalling carefully – reinforcing deterrence without feeding Chinese narratives of encirclement.”

Beijing, for its part, needs to recalibrate its coercive tactics if it wants to rebuild regional credibility and demonstrate commitment to a peaceful dispute resolution, according to Gorska.

Noticeable absence

China’s reduced presence at the Shangri-La Dialogue could be seen either as a strategic move or an attempt to avoid uncomfortable questions, Jimenez said.

Regardless of intent, such an absence limits opportunities for dialogue and trust-building. “Asean should play a more active role in proposing alternative diplomatic frameworks for resolution,” he said.

Beijing’s decision to downgrade its participation – sending Rear Admiral Hu Gangfeng instead of Defence Minister Dong Jun – signalled to Manila its reluctance to engage in high-level, multilateral security dialogue, particularly at a time of intensifying US-China tensions, Gorska said.

“China’s ministerial no-show effectively deprived the forum of opportunities for meaningful bilateral engagement or public rebuttal at the highest level. Philippine officials have interpreted this as Beijing deliberately sidestepping accountability,” she said.

“It reflects Beijing’s broader pattern of selective multilateralism: while China champions multilateralism in economic forums, it consistently prefers bilateral channels when addressing sovereignty disputes or sensitive security matters, where power asymmetries favour Chinese leverage.”

But such a strategy carried long-term risks, she warned. By avoiding public multilateral forums, China was ceeding narrative ground to the US and its regional allies, allowing them to reinforce the perception that Beijing was a disrupter rather than a cooperative security stakeholder.

“For the Philippines, this undercut hopes of advancing trust-building through regional mechanisms and may push Manila even further into US-led security frameworks, including emerging trilaterals with Japan.”