Beijing’s marine science diplomacy can calm South China Sea tensions

With heavy investment in ocean technology and scientific expeditions, China is set to shape a collaborative scientific agenda in the region

The South China Sea has long been a flashpoint in geopolitical tensions, but beneath its contested surface lies one of the planet’s most scientifically compelling marine frontiers. Home to an array of deep-sea ecosystems, hydrothermal vents, underwater mountain ranges and vast coral reef systems, the region is increasingly recognised as a natural laboratory for cutting-edge oceanographic research.

Climate change, biodiversity loss and overexploitation are putting mounting pressure on marine environments worldwide. Amid this, the South China Sea stands out for its environmental significance as well as the diplomatic opportunity it presents: a chance to pivot from conflict to cooperation through shared scientific enterprise.

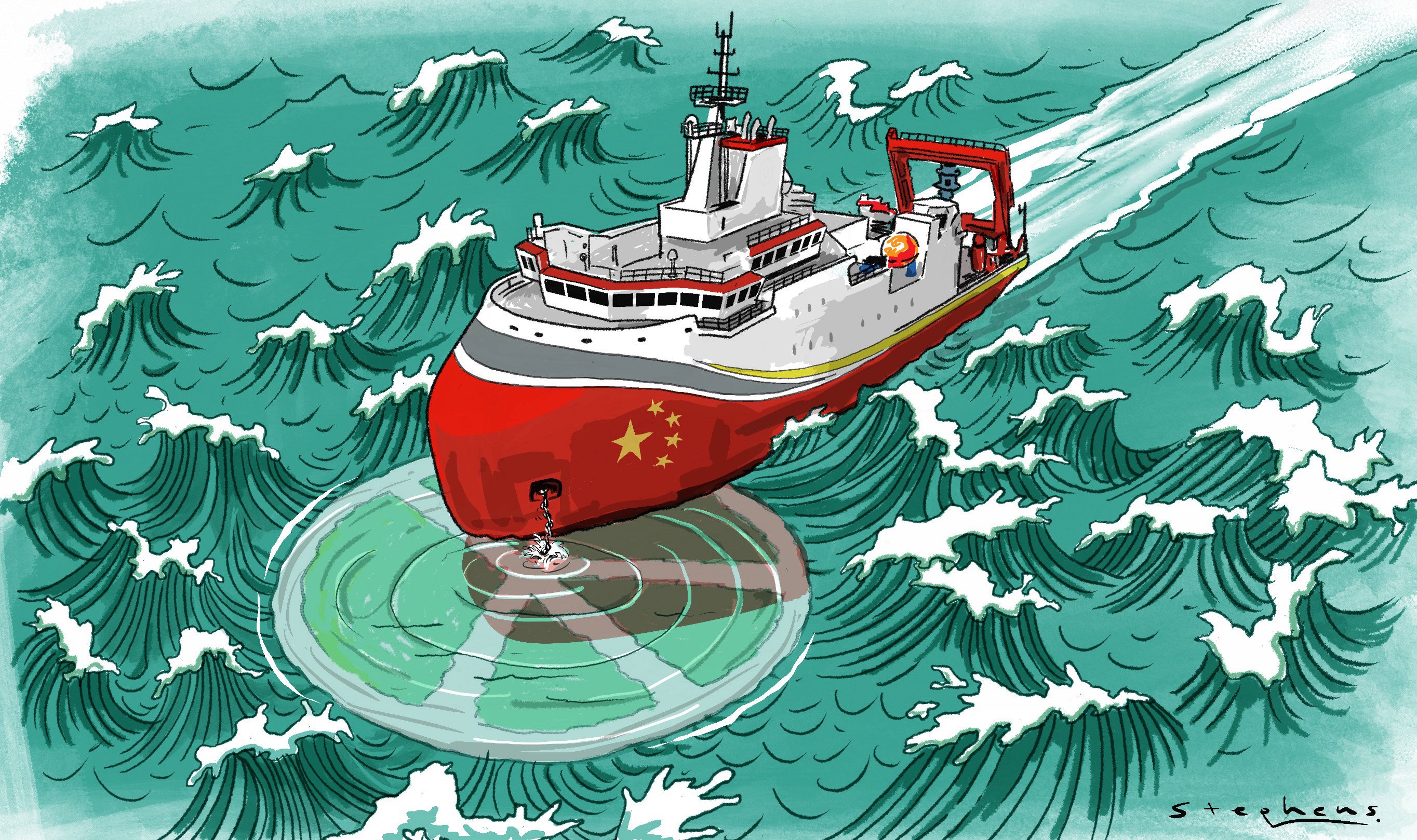

In recent years, China has asserted itself at the centre of this emerging science-based diplomacy. With heavy investment in ocean technology, scientific expeditions and international research partnerships, Beijing is now poised to take a leadership role in shaping a collaborative marine science agenda in the region.

Central to this effort is the vision of building a network of marine protected areas across the South China Sea. Unlike isolated conservation zones, these areas are designed to function ecologically and operationally as interconnected systems. They facilitate the movement of marine species, enhance genetic diversity, provide resilience against climate stressors such as ocean acidification and warming seas, and serve as platforms for international research.

Spanning around 3.5 million sq km, the South China Sea is one of the world’s most ecologically and geologically rich marine regions with more than 3,000 fish species, vibrant coral reefs and largely uncharted deep-sea habitats. Its sea floor holds vital clues to the Earth’s geological past and the unfolding story of global climate change.

Marine scientists see this area as a treasure trove of research opportunities. A forum organised by the journal National Science Review at the Annual Conference of the South China Sea-Deep Programme, held in January in Shanghai, highlighted the region’s significance as a “fantastic natural laboratory” for deep-sea research and emphasised the importance of international collaboration in exploring and preserving these ecosystems.

China’s efforts to build this collaborative framework are becoming more visible. Through institutions such as the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing has launched multinational expeditions and invited regional and global partners to join in data sharing, capacity building and joint marine monitoring programmes.

China’s scientific outreach in the South China Sea comes amid persistent geopolitical disputes over maritime claims, resource rights and military presence. Even so, there is a growing sense within the marine policy community that science can act as a neutralising force, offering a platform for constructive engagement even when political dialogue stalls.

In a keynote address at the Boao Forum for Asia in March, Vice-Foreign Minister Chen Xiaodong described China’s role as an “anchor for peace” in the South China Sea, emphasising that regional stability hinges on a shared commitment to dialogue and cooperation to manage maritime tensions.

Beijing appears to recognise the value of this soft-power approach. In the past decade, it has steadily increased funding for marine research vessels, such as the Tan Suo Yi Hao and Xiang Yang Hong 01, equipped with state-of-the-art submersibles capable of diving to 10,000 metres.

Although some countries remain wary of China’s strategic intentions, there is also cautious optimism that science-based cooperation could serve as a confidence-building mechanism.

China reportedly maintains more than 270 marine protected areas within its coastal waters, a reflection of its growing acknowledgement of ecological challenges such as overfishing, coastal pollution and ocean acidification.

These issues are particularly acute in semi-enclosed seas such as the South China Sea, where cumulative stressors threaten the integrity of entire ecosystems. Chinese scientists have warned about coral reef degradation and declining fish stocks in the region, further underscoring the urgency of scaling up conservation efforts.

China has already designated several marine protected areas within its claimed waters, but the vision now appears to be scaling up. According to sources close to the Ministry of Natural Resources, there are plans under way for China to join a regional conservation network that could include co-managed marine protected areas, or shared zones with neighbouring countries based on ecological importance rather than territorial claims.

Such a network would align with global conservation goals under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which calls for protecting 30 per cent of the world’s oceans by 2030. As a signatory to the agreement, China is under pressure to demonstrate measurable action. Leading a cooperative marine protection initiative in the South China Sea could provide the political and environmental dividends needed to fulfil that commitment.

Significant hurdles persist, including the absence of a regional legal framework for transboundary marine protected areas, ongoing geopolitical tensions and limited data transparency. Scepticism is further heightened by concerns over China’s dual-use research infrastructure, which some fear could serve both scientific and military purposes.

Nevertheless, incremental progress through science-driven confidence-building measures could lay the groundwork for broader regional dialogue. Joint research surveys, collaborative management of marine protected areas and the establishment of a South China Sea marine science council are among the proposals gaining traction in diplomatic and academic circles.

If successful, China’s strategy could signal a pivotal shift in its South China Sea policy from assertive power projection to environmental stewardship, and from unilateral actions to science-led, shared governance. The outcome carries weighty implications for regional peace as well as the preservation of one of the world’s most fragile and vital marine ecosystems.