Asian shippers fear spiralling costs as Iran threatens Strait of Hormuz closure

Apart from soaring oil prices, Asian economies have to factor in a surge in insurance premiums and potential supply disruptions

US air strikes on Iran sent oil prices soaring on Monday, leaving Asian shippers burdened with fresh costs on top of extra insurance premiums of US$1 million more per tanker, as Tehran threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz and paralyse the crucial sea lane.

Up to 20 million barrels of oil pass each day through Hormuz, one-fifth of global supply, most of it destined for East Asia’s biggest economies – China, South Korea and Japan.

The neck of water is controlled by Iran, whose parliament on Sunday approved the closure of the shipping lane in response to the US joining Israel’s bombardment of the country.

Any closure of Hormuz will have global ramifications for the Gulf oil-producing nations and the export markets of Asia.

Oil spiked to close to US$80 on Monday morning from US$60 a barrel at the beginning of June.

Any prolonged rise is likely to soon be felt by Asian consumers.

Tunku Mohar Mokhtar, a geopolitical analyst at Malaysia’s International Islamic University, said that a decision to close Hormuz would affect energy prices and energy supply to the Asian market.

“China is Iran’s largest oil customer and any disruption in supply can affect Beijing’s economy,” Tunku Mohar said. “In addition, the prospective closure of the strait can also increase trade costs for goods that usually use the waterway.”

According to US Energy Information Administration’s data, Iran exported an average of 1.5 million barrels of oil per day in early 2024, 90 per cent of which were destined for China. In March, China’s oil imports from Iran rose to an all-time high of 1.8 million barrels per day.

The cost to insure a vessel for the journey via Hormuz has risen from US$0.20 a barrel to US$0.80, according to Athens-based shipbrokers Xclusiv.

Before the US strikes, credit rating agency Fitch Ratings warned on June 16 that Yemen’s Houthi group could attack shipping routes in defence of its ally Iran.

The government in Sanaa, controlled by the Houthis, said on Sunday it was “ready to target US ships and warships in the Red Sea” following the US air strikes.

In 2023, the Houthis carried out a series of missile strikes in response to Israel’s attacks in Gaza, creating a chokepoint at the narrow Bab Al-Mandab in the Red Sea and causing a diversion of maritime traffic away from the Suez Canal toward the longer and costlier passage via the Cape of Good Hope off South Africa.

“There remains a risk that Iran’s response may be more disruptive than we expect. For example, an Iranian strike against US-related targets in the Gulf, including bases within the GCC, cannot be ruled out,” Fitch Ratings said, referring to the six-member Gulf Cooperation Council.

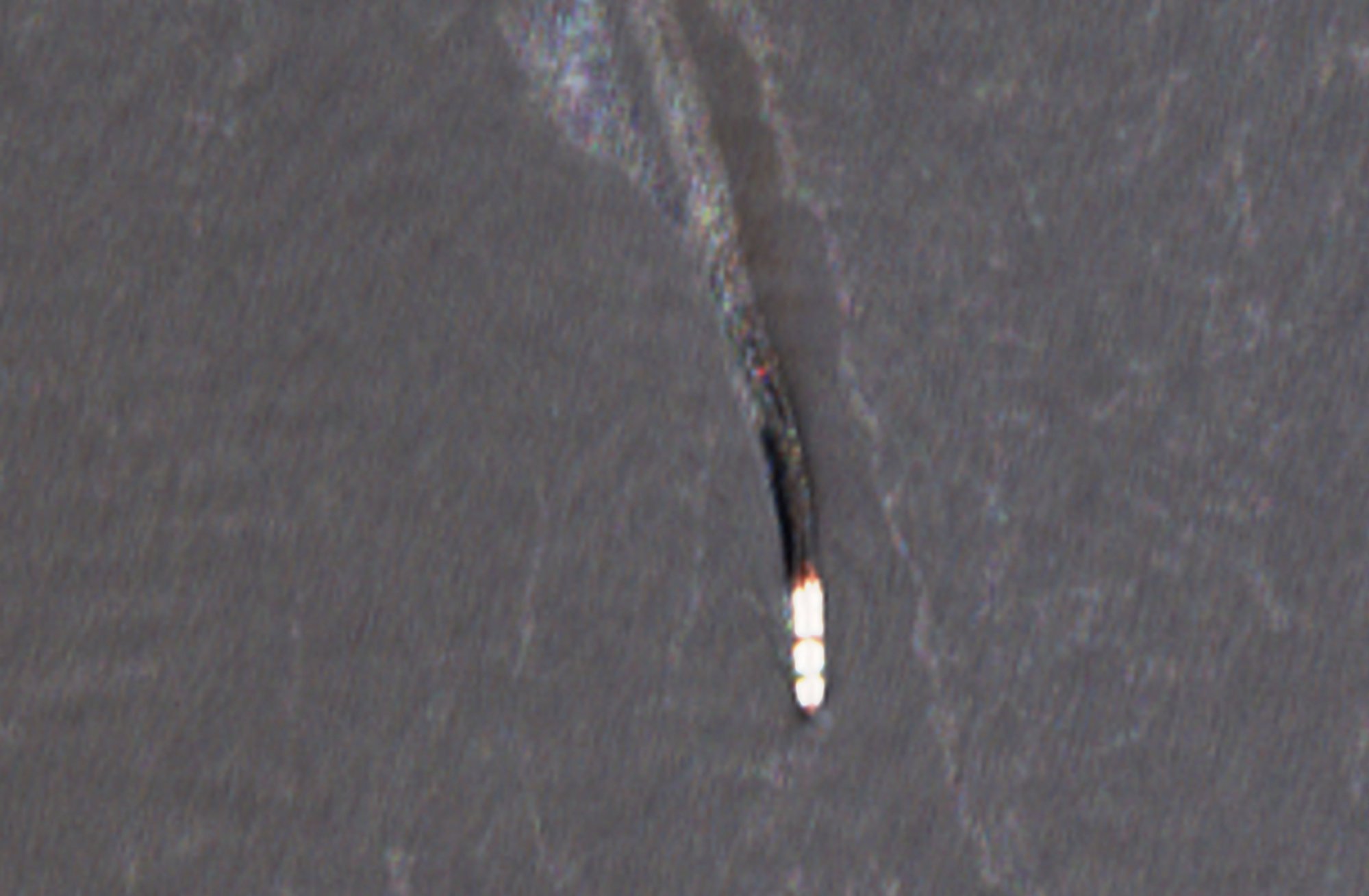

On Sunday, US President Donald Trump announced that the US military carried out an aerial attack on three nuclear sites in Iran, following days of appeals by Israel for the American military to join its attacks on the Islamic republic.

Trump called the operation “very successful” and demanded that Tehran must agree to end the war.

The US-led Joint Maritime Information Center, launched in February 2024 to share information on the Houthis’ attacks on merchant vessels, has placed the regional threat level at “significant” as strikes continue from both Iran and Israel against each other, and designated the maritime specific threat level as “elevated”.

Over a week, nearly 1,000 ships in the region had been affected by GPS jamming and interference believed to be by Iran, maritime intelligence firm Windward said on Thursday.

These attacks compromise the Automatic Identification System (AIS), which sends a vessel’s real-time position, speed and direction to help avoid collisions and aid maritime monitoring.

Two large tankers collided last Tuesday in Hormuz, believed to be a result of navigational misjudgment compromised by the GPS jamming in the area.

Over the past week, ships have appeared on navigational systems as if sailing on land – over the Omani desert, near Iran’s Bandar Abbas port, or even within Dubai – due to spoofed AIS signals.

Although Hormuz remained operational, the risk environment had deteriorated, Windward said.

“Shipowners, insurers, charterers, and energy traders are now reassessing maritime safety and security,” the agency said. “Persistent electronic interference has led to delays, diversions, and broader shifts in routing strategies as stakeholders attempt to navigate the growing operational uncertainty.”

Michelle Wiese Bockmann, a maritime intelligence analyst at Windward, said that jamming had been Iran’s preferred retaliatory tactic for the past six years, which usually resulted in a temporary disruption of Western-affiliated shipping traffic.

While Iran would unlikely close Hormuz, which would hurt Asia more than the West, or hijack ships, Tehran had “upped the maritime ante with this new tactic of GPS jamming”, Bockmann said.

“It’s persistent, severe and widespread,” she added.

Although Iran may issue threats, it does not have the means to fully dictate the decisions of shippers, according to energy analysts.

Hendrian Sukardi, an LNG market analyst at ENN Energy, said that while Hormuz was always a risky waterway, it would rarely lead to prolonged market ruptures.

“Iran can provoke, but cannot dominate. And markets? They trade on fear as much as fact,” Sukardi said.