Asean firms in limbo as Trump’s 90-day tariff window ticks, China ‘dumping’ fears grow

Companies brace for drop in demand and profits as they and regional governments struggle to find a way to tackle the punishing duties

Malaysian luxury watchmaker Ming has carved out a niche following with its minimalist designs and Swiss craftsmanship.

But a third of its customers are in the United States and now stuck on the wrong side of a tariff barrier thrown up by President Donald Trump, casting a long shadow over future sales.

“It doesn’t matter whether we export as Malaysian or Swiss – for the US customer, the landed cost has effectively gone up by 30 per cent,” said Ming Thein, the brand’s co-founder. “That’s going to hurt demand, no question.”

One month after Trump’s self-professed “Liberation Day” levies unveiled on April 2, Southeast Asian companies with a US market are running the numbers on what their business may look like in a few days, weeks and months.

But crystal ball gazing for the long-term has diminishing returns, as the White House rows back duties on some sectors – semiconductors and electronics – and then adds more taxes on others like solar.

At the same time, the Trump administration has turned the screw on trading partners with a 90-day deadline to find an agreement or live with punishing levies that range from 10-49 per cent across Asean.

Most Malaysian goods face a 24 per cent tariff.

That has left companies with multiple bases and reliant on complex manufacturing – such as luxury watches – in a costly limbo.

Ming has facilities in Switzerland – itself slapped with a bigger 31 per cent tariff – and elsewhere around the world, making the impact both “potentially significant and complex”, Thein added.

“The initial reactions of shock have now given way to practicality: how can we find a solution?”

For a company like Ming, which exports over 95 per cent of its products and counts the US as a third of its market, the hit could be significant as Americans recoil from sticker shock from tariffs on Chinese products sold on Temu, Shein and Amazon.

“It feels like another challenge in a never ending string of them,” Thein said.

“We had self-imposed ones through setting up in Malaysia, worldwide ones through the pandemic, domestic ones from the shift in taxation, currency devaluation and now Trump.”

Tariff pinball

Planning inventory, paying suppliers and booking transport has become a fool’s errand, companies told This Week in Asia, in what amounts to a freeze on business confidence.

It is a game of trade pinball, where wins have been counted: Thai exports surged in March ahead as retailers stockpiled before Trump’s announcement, but losses are also mounting.

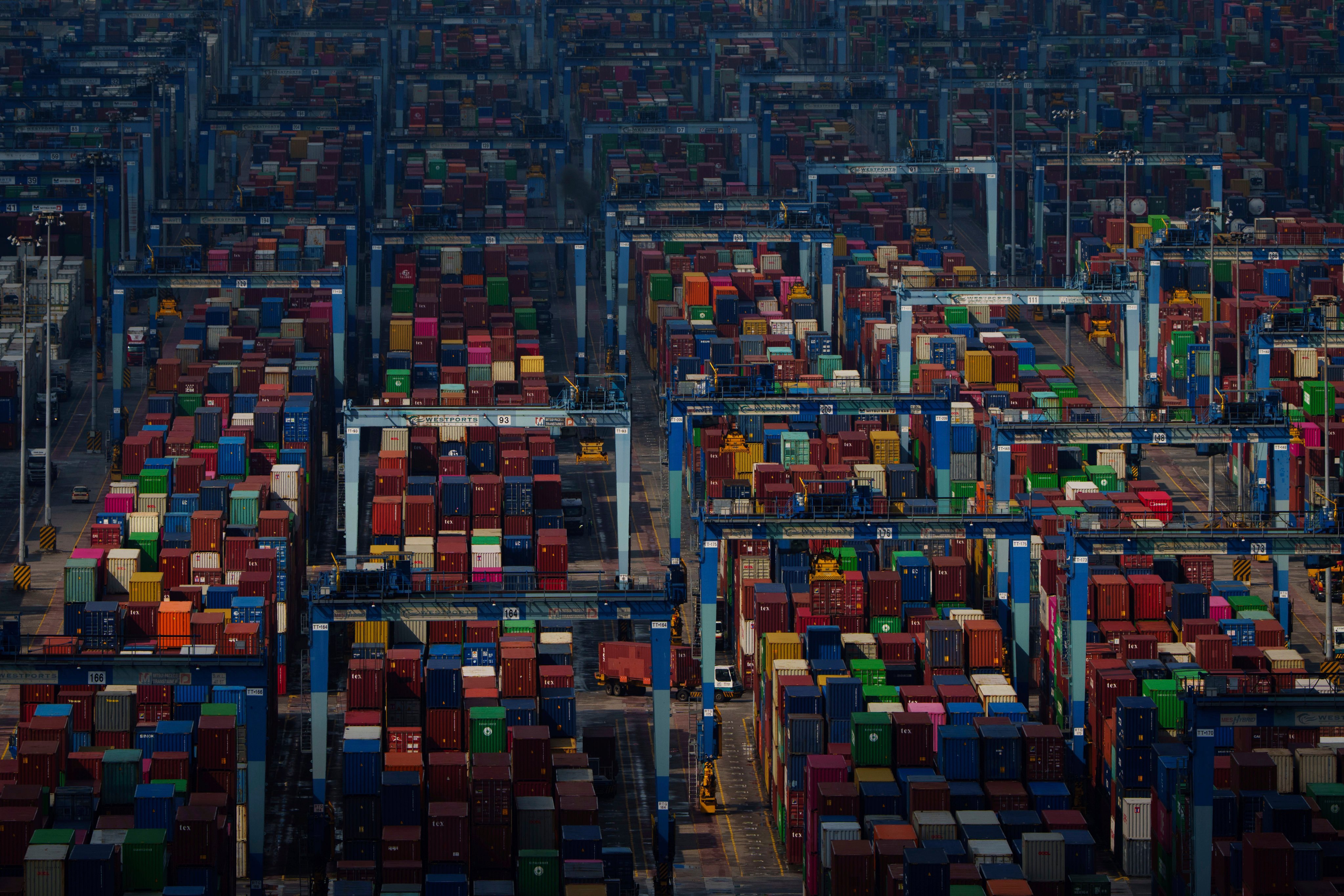

Twenty-two container ships were this week anchored off Malaysia’s Port Klang as congestion seizes up ports across the region, according to an Australian logistics tech firm.

Sources at the Malaysian port attributed the clogging to shippers rushing to move their cargo within Trump’s 90-day deadline, with some vessels waiting three days for a berth.

Governments are also flailing around in the dark for an apt response.

Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia have struck out on their own to make deals with Washington – despite vague language on the unity of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Thailand has held back so far, but its leaders have been forced into increasing verbal contortions to neither reveal their full hand, nor upset the US and China, which wants its Southeast Asian allies to call Trump’s bluff and reject trade pacts at the barrel of the tariff gun.

Thailand may hit some “air pockets”, Finance Minister Pichai Chunhavajira said on Thursday after growth forecasts were trimmed by nearly one point to 2.1 per cent for the Southeast Asian kingdom.

“No matter how the tariff will end up, if it is at an equal level and equal to our competitors, it will not affect us,” he added.

The trade whiplash has landed unevenly across Asean. Some nations, like Singapore, enjoy lower tariff rates under US trade classifications. Others, like Malaysia, are caught in the ambiguity of how American customs authorities will interpret multi-origin supply chains.

Certificates of origin – once a bureaucratic formality – are now viewed with suspicion.

As the 90-day tariff pause window ticks, manufacturers worry goods diverted through Southeast Asia may be retroactively penalised.

“If moving to Singapore would solve it, everyone would be transhipping from zero-tariff countries,” Thein said. “Until we know the answer to this, all we can do is speculate.”

Singapore, which has a free-trade agreement with the US, is itself slapped with a 10 per cent “nominal tariff”, a move that incurred a rare rebuke from the trading-dependent city state.

The lack of clarity around final tariffs or their enforcement – especially how the US will determine the “country of origin” – has frozen business decisions, as Chinese supply chains hesitate over rebasing to third countries with lower duties to build and export their products.

For Malaysian electronics manufacturer Otax, the concern is less direct exposure to the levies – it is the ricochet effect on the local market.

“If Chinese firms can’t sell to the US, they’ll look here – just like they did 10 years ago,” said Otax Malaysia managing director Long Fong Ping. “That could trigger a new wave of dumping.”

The company, which produces dip switches used in factory automation and appliances, has factories in China, Thailand and Malaysia.

About half its orders come from US-linked clients, but are routed regionally, shielding it from immediate impact. Still, suppliers have begun reporting sudden drops in demand, a worrying sign.

“Clients are already asking us to match lower prices offered by others. That puts huge pressure on local firms,” Fong Ping said.

The firm fears a repeat of what happened under former prime minister Najib Razak’s Beijing-friendly investment push, when an influx of Chinese manufacturers drove price wars that hurt domestic players.

“Even those that didn’t build factories here just shipped in bulk and undercut us,” he said. “Having our own factories in China didn’t help.”

There are some upsides.

The weeks of trade chaos have accelerated Asean’s search for new partnerships.

On April 24, Malaysia concluded a long-stalled free-trade agreement with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) – comprising Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein – after more than a decade of negotiations.

“The tariffs were the catalyst,” said Grimur Grimsson, head of Iceland’s parliamentary delegation. “It closed the deal after more than 10 years of talks.”

Norwegian and Swiss officials said companies are now eyeing Malaysia more closely as a China alternative, particularly in sectors like renewable energy, maritime logistics and precision manufacturing.

“Malaysia offers a good middle option – more advanced than Vietnam, but more affordable than Singapore,” said Thomas Aeschi, head of the Swiss delegation.