As Malaysia’s Huawei chip storm shows, sovereign AI is a fraught pursuit

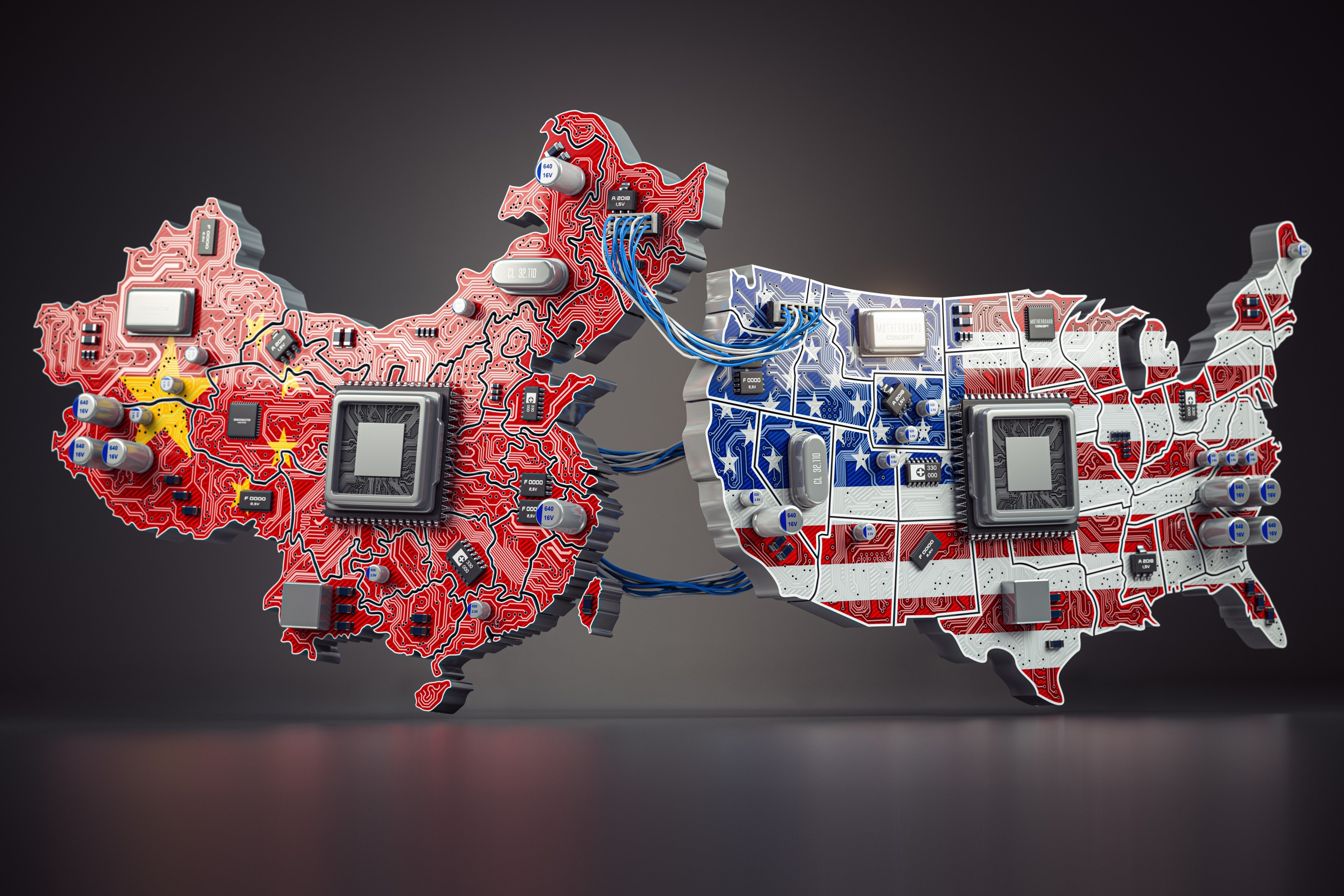

For third states, what is there to differentiate a Chinese AI stack from an US one when both lock in external reliance in the longer term?

When Malaysia’s deputy minister of communications, Teo Nie Ching, announced the launch of the country’s “sovereign AI infrastructure” powered by Huawei Technologies’ advanced computing chips and the DeepSeek large language model, she inadvertently set off a geopolitical maelstrom.

In the crosshairs of Teo’s announcement was the activation of Huawei’s Ascend chips on a national scale and the planned roll-out of 3,000 of those chips by next year to “form the backbone of Malaysia’s national AI grid”. Teo’s office reportedly retracted her remarks just a day later. Had they been true, Malaysia’s deployment of this class of Huawei’s integrated circuits could have fallen foul of US export controls targeted at specific Ascend chips, issued just a week earlier.

Malaysia’s Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry distanced itself from Teo’s announcement, clarifying that the artificial intelligence infrastructure touted was “privately driven” and “not developed, endorsed or coordinated” at the government level. Even Huawei, whose vice-president of Malaysia operations attended Teo’s event, denied selling any Ascend chips in the country when asked by the media.

The incident threw a spotlight on the increasingly difficult positions of Southeast Asian countries walking the tightrope between technological autonomy and fracturing geopolitical realities. Beijing has threatened to retaliate against Washington’s latest export controls on Chinese-made chips with its anti-sanctions law, which would affect third parties enforcing US regulations.

If Teo’s remarks were, in fact, verifiable, they would have implied double jeopardy for a Malaysia caught between the extraterritorial reach of the United States and China’s unilateral, punitive measures.

This dilemma begs the larger question of what a third country’s sovereign AI infrastructure might look like if it lacks or is denied sufficient tools, technologies and the tradecraft to build, operationalise and deploy AI services to its people. As even China and the US must realise, no country can yet construct, own and control its entire AI stack completely independently of others.

Technological advances have always been an experimental mix of public and private-sector innovations facilitated by complex global supply chains. Historically, they have also been built on the backs of invisible labour, resource extraction and, in the age of AI, copious amounts of data from everywhere.

Teo correctly observed that if Malaysia did not act decisively in the AI space, it risks becoming “perpetual consumers of technologies defined by others, running on infrastructure governed by others, under laws written by others”.

The irony is that owning and operating strategic, national AI infrastructure inevitably relies on high-performance, capital-intensive inputs from foreign sources, especially initially.

Physical infrastructure including subsea data cables, data centres and computing and processing units that collectively enable data flows and provide the computational power and storage capacity to power AI operations is costly, technically specific and enduring.

It often demands external investment and expertise which carry the long-term risk of cornering countries into the very foreign dependencies and barriers Teo warned against.

Is a national AI architecture run on Chinese integrated circuits, powered by DeepSeek’s open model and operating within a “trusted data zone” with China materially distinguishable from an AI stack underlaid by Meta or Google subsea data cables (incidentally bound by national security agreements with the US government) which connect to Amazon, Google or Microsoft data centres running on Nvidia graphics processing units (GPUs)?

In other words, what is there to differentiate a Chinese AI stack from an US AI stack in the eyes of third countries when both lock in external reliance for the longer term?

For many non-superpower countries aspiring to autonomy, sovereign AI looks realistically more like tweaking AI models or architecture for local use and governance, rather than constructing the stack from scratch.

In Southeast Asia, government, academic and corporate stakeholders have begun building home-grown language models to better cater to the cultural nuances of local populations and to mitigate against Western, English-language biases of large-scale, popular models.

For these developers, open-source models such as GPT-2 from OpenAI and Qwen from Alibaba Group Holding (which owns the South China Morning Post) have democratised access to less-represented languages such as Indonesian, Thai and Vietnamese as well as the perspectives they encode.

But even though openness generally disrupts the power asymmetry of a few well-resourced tech titans dominating large language models, not all open models are created equal. For example, many have refuted Meta’s claim that its Llama 2 model is open-source because of its licensing regime.

In some instances, openness may paradoxically result in greater centralisation due to market incumbency. There is a greater incentive for developers to create systems that align with Google’s TensorFlow or Meta’s PyTorch, both open-source frameworks for machine learning, since they already dominate pre-trained deep learning models.

For many countries, the pursuit of greater AI autonomy – or more accurately, degrees of sovereignty – is now more urgent given geopolitical pressures and technological fragmentation. But for these nations, it’s also a much longer, comprehensive arc in the making to unshackle their futures from the impulses of more powerful players.

As countries outline distinct notions of sovereign AI to suit their domestic contexts, Southeast Asian nations would do well to interrogate just how much autonomy is possible with differing levels of resources, coordination and capacity across the spectrum of AI systems. And with some private-sector players larger and more influential than smaller countries, who does sovereign AI ultimately serve?