Anwar’s chief justice pick tests Malaysia’s faith in the courts

As ex-Umno insider Wan Ahmad Farid Wan Salleh takes his seat at the apex of the judiciary, he inherits not merely a bench but a burden

As the gavel passes to Malaysia’s new chief justice, old questions echo through Putrajaya. Can a judiciary led by a former Umno party insider truly deliver impartial justice, or will the shadows of political allegiance darken the bench?

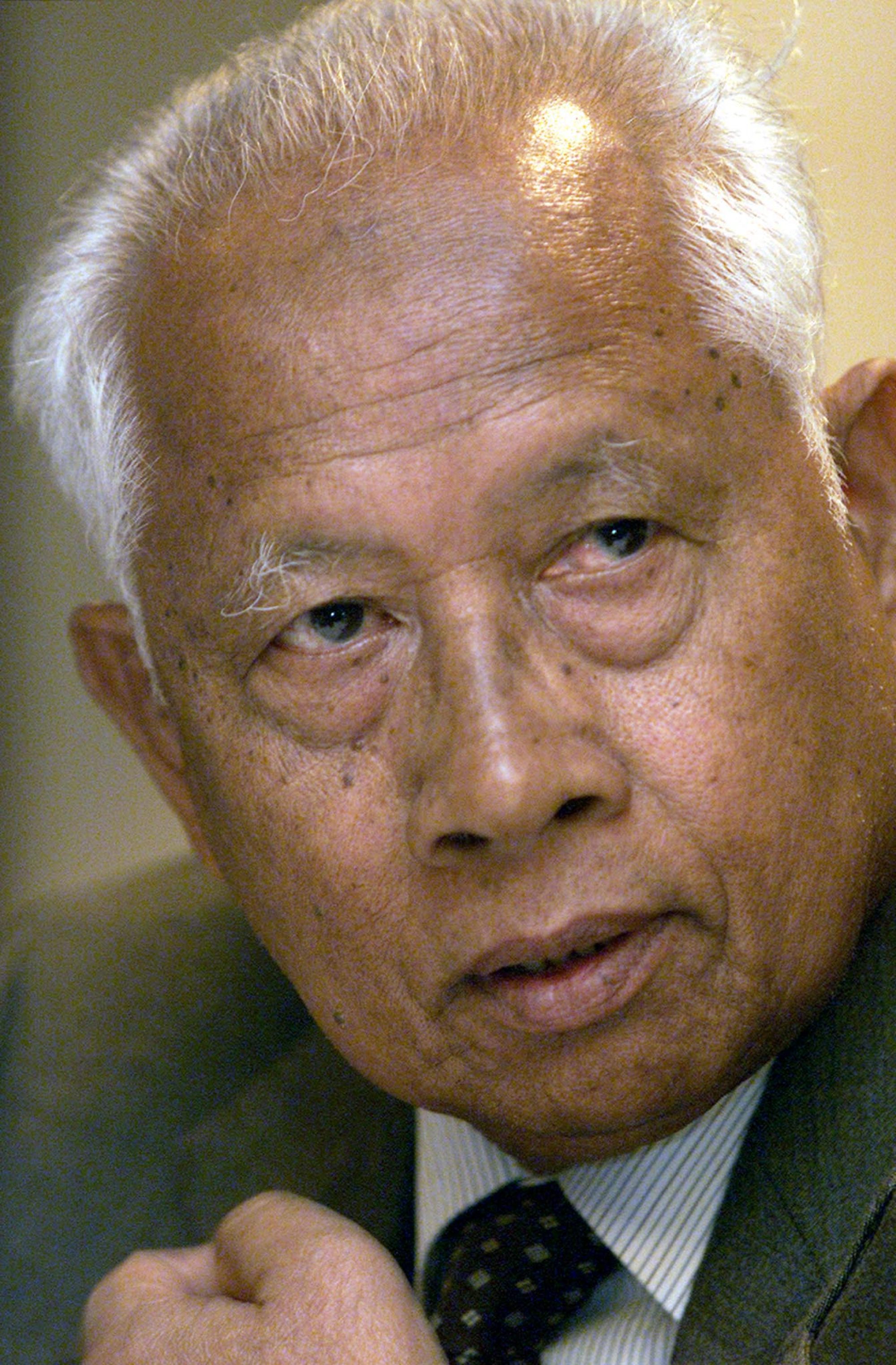

Wan Ahmad Farid Wan Salleh, previously a Court of Appeal judge and once deputy home minister under prime minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, is set to assume the judiciary’s highest seat on Monday.

But his past life as an Umno politician, and personal associations with disgraced ex-prime minister Najib Razak, have cast a long shadow over his appointment on July 18.

The timing is as sensitive as it is symbolic. Wan Ahmad Farid’s elevation comes just as the courts are poised to hear Najib’s contentious bid for house arrest.

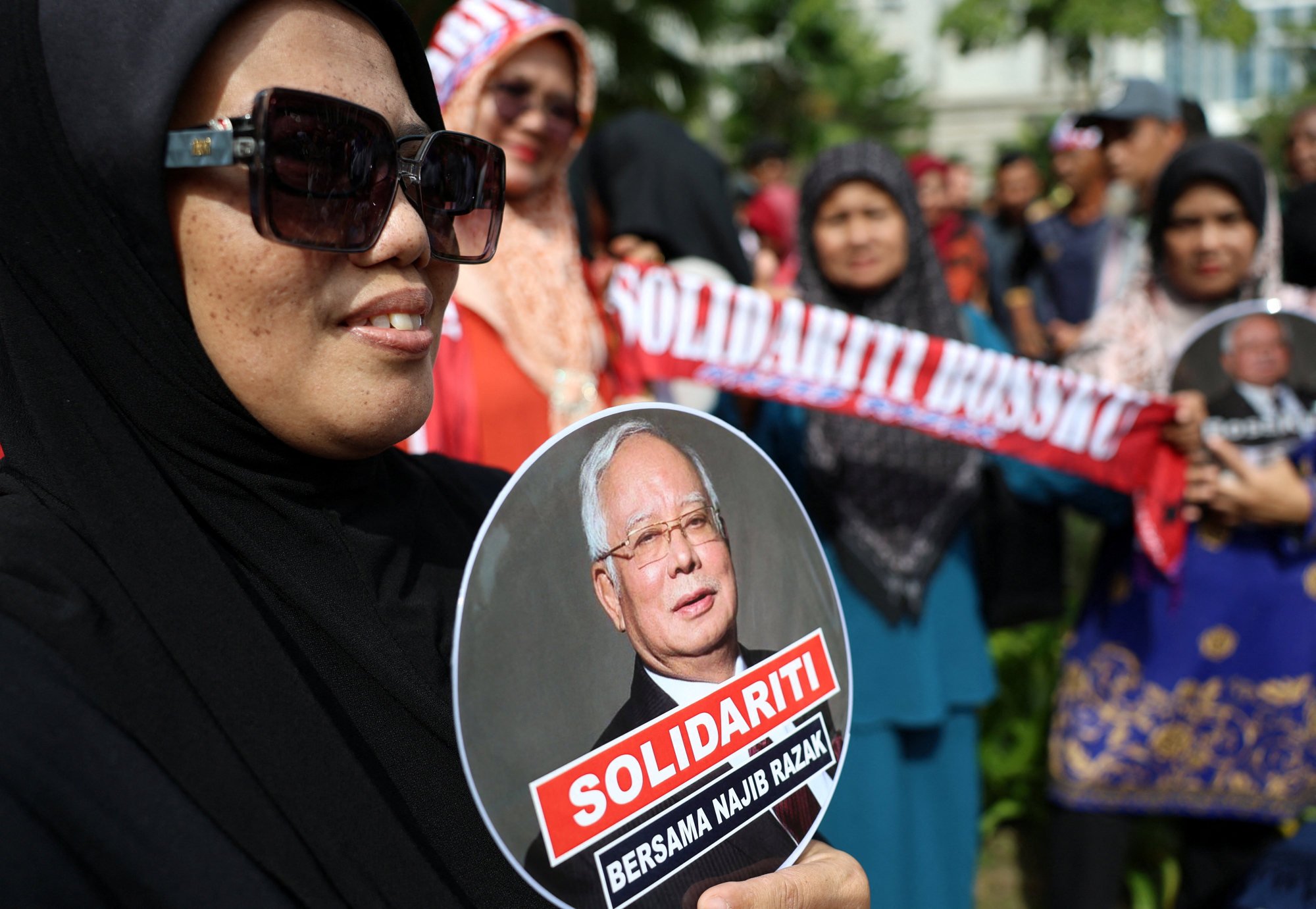

The former prime minister, convicted in 2021 of corruption linked to the multibillion-dollar 1MDB scandal and currently serving a six-year sentence, is seeking to exchange prison for home confinement – a move his lawyers claim is permitted by a royal decree the government has kept under wraps.

The case, alongside the ongoing appeal of Najib’s wife, Rosmah Mansor, and a string of other politically charged trials, has placed the judiciary at the centre of the nation’s debates over justice and power. Critics say the courts are once again open to accusations of political interference: allegations that have dogged Malaysia for decades.

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, acutely aware of the stakes, has acknowledged being pressured by members of the United Malays National Organisation over Najib’s house arrest application. “[But] the matter is already before the courts, and I cannot act ahead of the judicial process,” he said on July 18, seeking to reassure a wary public of the government’s respect for judicial independence.

The optics, however, are harder to manage than the rhetoric. “The position of chief justice is not just an ordinary judge. He is the highest symbol of justice in the country,” political satirist Fahmi Reza said in a social media post on Sunday. “Is it appropriate for a politician to hold this position? I guarantee you will agree that the answer is no.”

Court of public opinion

Such scepticism is rooted in history. In 1988, then prime minister Mahathir Mohamad orchestrated the sacking of chief justice Mohamed Salleh Abas and the suspension of senior judges he believed were undermining his administration in a watershed moment that shattered public faith in the courts.

Two decades later, a videotape showing senior lawyer V.K. Lingam brokering judicial appointments with then chief justice Ahmad Fairuz Abdul Halim triggered a Royal Commission of Inquiry in 2007, which found credible evidence of political meddling but resulted in no prosecutions.

For many Malaysians, high-profile corruption trials have long resembled political theatre, with the ruling elite accused of using the courts to settle scores rather than pursue justice. Yet Najib’s conviction in 2021 appeared to mark a turning point – a rare instance of the law reaching the very top, persuading some that the judiciary was at last shedding the yoke of executive control.

Still, to Najib’s supporters, the verdict only confirmed their belief in selective prosecution. They claim that only those who are out of favour, such as former prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin or government critic Muhammad Sanusi Mohd Nor, find themselves in the dock.

Former chief justice Tengku Maimun Tuan Mat, who presided over Najib’s final appeal in 2022, was pilloried by Najib loyalists who accused her of bias.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

Defenders of Wan Ahmad Farid argue that he is more than his political past. They note his 2022 decision to recuse himself from a Najib-linked case – a gesture the Malaysian Bar Council described as “a profound understanding of the judiciary’s sacred role in upholding the rule of law”.

Criminal lawyer Naran Singh told This Week in Asia that the new chief justice deserved the benefit of the doubt. “It’s unfair to him. He has yet to sit on the chief justice’s chair. Let’s see how he performs first.”

The Malaysian Bar, for its part, said in a statement that it was “relieved” by his appointment.

‘Trust deficit’

Such endorsements have not silenced the doubters, however. Wan Ahmad Farid, 62, hails from a family deeply entwined with Umno, served as deputy home minister from 2008 to 2009 and was once political secretary to Abdullah Badawi. His 2009 by-election nomination received Najib’s personal endorsement, calling him “the right candidate”.

“We have so many judges to pick from – why did we have to go with a judge as exposed as this?” said one lawyer, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Despite Wan Ahmad Farid’s insistence that his political days are behind him, detractors say his former loyalties render him vulnerable to allegations of conflict of interest, which are likely to be tested in the months ahead.

And the concerns are just not hypothetical. Najib’s legal team previously sought to disqualify his trial judge, arguing that the judge’s past work for a bank involved with 1MDB created “grounds for a reasonable person to believe that he cannot act with an objective mind”.

They also attempted to remove Tengku Maimun from Najib’s appeal, citing a Facebook post by her husband critical of Najib after the 2018 general election. Both efforts failed, but each fuelled suspicions among Najib’s supporters that the process was stacked against him.

For many Malaysians, the real issue runs deeper than any one judge. “The public, especially those who opposed Umno for its power excesses, is sceptical of an ex-Umno chief justice,” said political analyst Tunku Mohar Mokhtar of Malaysia’s International Islamic University. “The problem here is the trust deficit.”