Anwar Ibrahim mints a dynasty – but Malaysia’s youth aren’t buying it

The rapid ascent of Anwar’s heir apparent Nurul Izzah has alienated many young Malaysians who are tired of old feuds and unfulfilled promises

Anwar Ibrahim’s decades-long struggle for reform once inspired a generation to take to the streets, railing against corruption and cronyism.

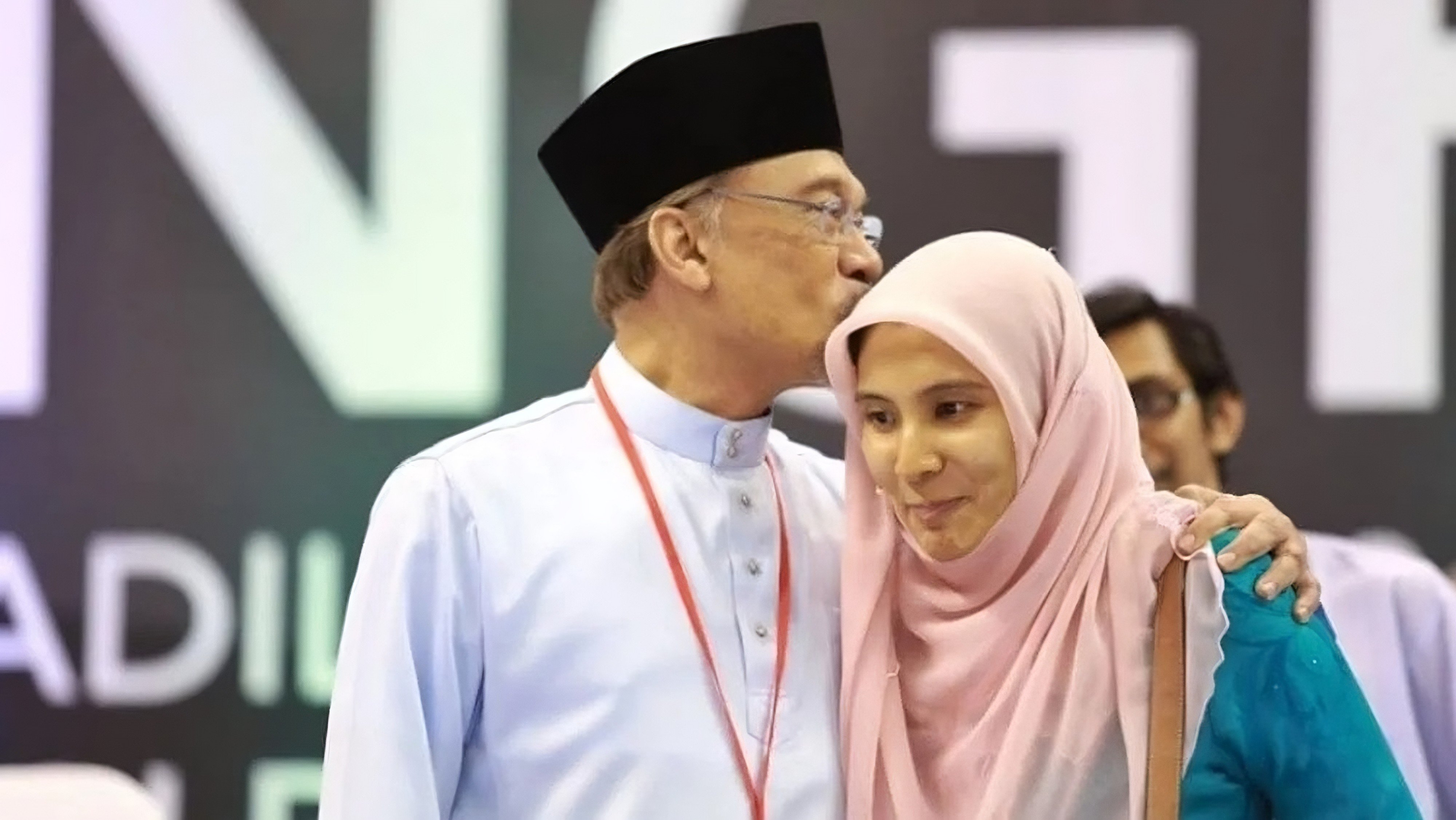

But two years into his tenure as prime minister, the political realities of governance have begun to erode his once-revered “Reformasi” brand. Critics accuse him of compromising principles for political survival, settling old scores and devising a dynastic succession through his daughter, Nurul Izzah Anwar.

These are not qualities likely to inspire Malaysia’s 10 million young voters, many of whom feel besieged by the rising cost of living, stagnant wages, a failing healthcare system and schools that do not prepare them for the future job market.

“People said only he could fix the country,” Ahmad Riza, a 25-year-old marketing executive, told This Week in Asia. “But two years on, he’s just another politician.”

His sentiments echo those of many within his generation. While voters aged 18 to 39 were decisive to Anwar’s win in the 2022 general election, polling suggests they are increasingly indifferent to the political mythologies that defined their parents’ loyalties.

“My father was a big fan,” said Tobias Lim, a 20-year-old engineering student. “But I never quite understood why. I see him as a politician for the older generation, not so much for the people my age.”

This generational divide presents a problem for Anwar. By the time Malaysians return to cast their ballots at the next election in 2028, the youth vote will carry even greater weight as older voters pass on.

It is a conundrum he hopes his 44-year-old daughter can help resolve.

Erudite and well-versed in her father’s reformist ideals, Nurul Izzah is now being fast-tracked for the political spotlight. Yet she is also a relative political neophyte and currently holds little sway among a younger generation that feels neglected by those in power and is uninterested in party feuds and family politics.

For now, she insists she harbours no ministerial ambitions, but experts say she is being groomed for high office, starting with her successful bid to become deputy leader of the ruling Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) following a party election on Friday. She defeated the incumbent, Economy Minister Rafizi Ramli, who previously said he might step down from the cabinet if he were to lose his post as the PKR’s deputy president.

Nurul Izzah’s rise mirrors a growing pattern of dynastic handovers among Southeast Asia’s political families, as ageing patriarchs seek to maintain influence through their children.

In Thailand, Paetongtarn Shinawatra, the 38-year-old daughter of tycoon and ex-prime minister Thaksin, now leads her father’s party.

Indonesia’s former president, Joko Widodo, paved the way for his son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, to ascend to the vice-presidency before stepping down.

The Philippines, meanwhile, has seen the presidency rotate among the Marcos, Aquino and, more recently, Duterte families, with President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr and Vice-President Sara Duterte – both children of former presidents – currently locked in a power struggle.

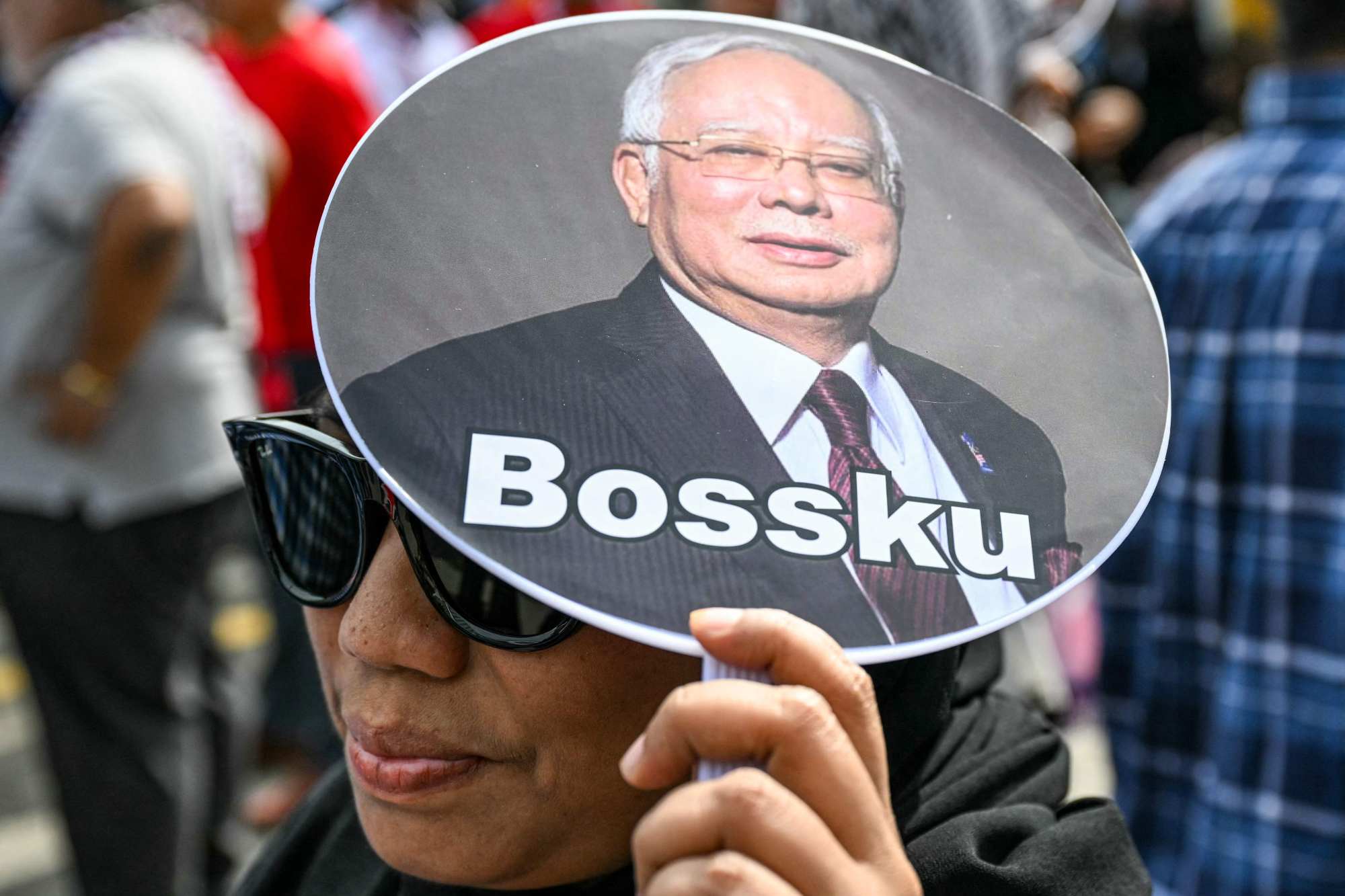

Malaysia is no stranger to such dynasties. Former prime minister Najib Razak is the son of the country’s second leader, Tun Abdul Razak, while his cousin Hishamuddin Hussein – another prime minister’s son – is an ex-defence minister.

Malaysians call these networks of family and friends “cables”, which, for those outside them, represent unfair advantages – often abused to secure business deals, climb the political ladder, or evade legal trouble.

“The public will have a trust issue with Anwar,” said political analyst Tunku Mohar Mokhtar. “He opposed nepotism, but this is now happening in PKR under his watch. It was once thought of as a reform party, now to many, it is becoming a party of personage.”

Political princess

Nurul Izzah was once seen as a symbol of Malaysia’s future and hailed as the “Princess of Reform”, appearing in photos supporting her father’s Reformasi movement.

Now, with Anwar at the height of his political career, his eldest daughter chairs an advisory board to the finance ministry and has risen to become the PKR’s new No 2, a development that could position her to eventually succeed her 77-year-old father.

Her entry into the race was met with cries of nepotism – allegations she has dismissed.

“Regardless of the titles and perceptions thrown at me over the decades, I will continue to serve, God willing,” she said on May 9. “Because I am convinced that the process of openly contesting and then receiving a mandate from the grass roots is not a form of nepotism.”

But for many young voters, her emergence seems out of step with the future they envision for Malaysia. Despite becoming the largest cohort among the electorate since the voting age was lowered from 21 to 18 in 2019, they feel their voices are not being heard.

The contest for PKR’s No 2 seat has also opened a rift in the ruling party between those loyal to Nurul Izzah and others backing Rafizi.

Both camps tout their legacies: Rafizi is heralded as an anti-corruption campaigner who blew the whistle on more than a dozen scandals under past administrations, while Nurul Izzah is lauded for her early and enduring role in her father’s reform movement – standing steadfast alongside her mother and younger siblings when Anwar was jailed in 1999 amid a prolonged feud with two-time prime minister Mahathir Mohamad.

Yet for today’s youth, the Reformasi movement that electrified Malaysia in the late nineties feels like ancient history.

“I know she did a lot of things in the past but I haven’t heard much about her until she started contesting as his deputy recently,” 25-year-old Ahmad said of Nurul Izzah. “But to me, first and foremost, she is Anwar’s daughter.”

Those under 40 largely had their political consciousness shaped by the fall of Najib in 2018 amid the multibillion dollar 1MDB scandal, followed by the upheaval of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Najib’s nine years in power – and his previous stints as deputy prime minister and defence minister – left a particularly deep imprint, with infrastructure projects like Kuala Lumpur’s mass rapid transit system and the East Coast Rail Link, as well as student book vouchers and cash handouts for the poor, all parts of his legacy.

Anwar’s public image, by contrast, has been defined by his protracted battle with mentor turned rival Mahathir, a jail term for sodomy he maintains was politically motivated and his long, exhausting quest to become prime minister.

While his overseas trips and investment announcements dominate headlines, many Malaysians say they feel little tangible benefit. To them, his lofty slogan “Malaysia Madani” – which most struggle to define – has become shorthand for rising living costs and unfulfilled promises.

In fact, young Malaysians are left cold by most current front-rank politicians, according to Aziff Azuddin of Kuala Lumpur-based think tank Iman Research – with one exception.

“If you asked young people who they trust and know, it’s Khairy Jamaluddin, supported by his past experience as a somewhat capable health minister,” Aziff said, referring to the 49-year-old politician who served as Malaysia’s health chief amid the pandemic from August 2021 to November 2022.

Something of a maverick, he has also avoided the negative associations of political dynasties, despite being the son-in-law of former prime minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi.

Khairy’s bold bid for the presidency of Umno in 2018 after the long-ruling party lost that year’s election won him accolades. Ultimately defeated and ejected from the party before the next leadership election in 2023, he subsequently reinvented himself as a morning radio presenter and host of Malaysia’s most popular current affairs podcast.

‘They care, and that’s good!’

Despite all major parties having youth wings and youth empowerment dominating discourse since the voting age was lowered in 2018, a disconnect persists.

“Young people no longer have the same opinions or ideas as the older generations,” Yuveraaj Pillai Kalidasan, a PKR youth leader from the Kuala Lumpur division of Batu, said on Monday.

“We want not only opportunities or space to voice out, we also would like to see our ideas implemented as policies across various matters like the education system, climate change and political system.”

But Yuveraaj, 23, says many of his peers simply toe the line with older leaders rather than push for change.

“The youths can’t relate. Politicians or governments rarely speak our language, solve our problems or think like us,” he said.

The youth can’t relate. Politicians or governments rarely speak our language, solve our problems or think like usYuveraaj Pillai Kalidasan, PKR youth leader

Muda, a youth-oriented party, was founded in 2020 to address this gap, unburdened by Malaysia’s entrenched racial politics, legacy loyalties and political grandees.

Its acting president, Amira Aisya Abdul Aziz, 30, argues that today’s generation is shaped more by what they see online than by what traditional institutions – or even their parents – tell them.

“I don’t see that as a bad thing. It reflects a shift in how political narratives are being shaped today,” Amira told This Week in Asia.

Young people who grew up on a diet of unfiltered social media commentary rather than polished television talk shows want leaders who both understand their frustrations and do not belittle them, she says.

“They’re incredibly diverse, and yes, they’re polarised but that’s the reality of a thinking generation,” she said. “They care, and that’s good!”

Muda’s sleek branding, monochrome visuals and strong online presence helped it stand out, but its political impact has been limited. In the 2022 general election, it contested six parliamentary seats but won only one. In the Johor state election that same year, the party secured just one of seven seats.

Only two of its members hold elected office: Amira in the Johor state assembly, and its charismatic former leader Syed Saddiq Syed Abdul Rahman in parliament.

Muda’s reliance on Syed Saddiq has been both a strength and a weakness. His 2024 resignation following a corruption conviction that he is appealing against left the party floundering, and critics say it has struggled to connect with rural voters.

“They do not have the political, cultural – or financial – capital to be publicly relevant,” Aziff said.

But as Malaysia’s political landscape fragments, old assumptions about voter loyalty are crumbling.

For insurgent movements like Muda, the challenge now is seizing the moment – especially if Anwar pursues a familiar path towards dynastic politics.

“The real question,” Amira said, “is are we present in the spaces where young people are having these conversations?”

Malaysia’s youth, meanwhile, are left waiting for leaders who can speak their language, share their frustrations – and deliver on promises of a better future.