‘Silent epidemic’: how online gambling is ravaging Filipinos’ lives

As addiction to online gambling grows, rehabilitation groups in the Philippines are urging the government to act – before it’s too late

In the dim glow of his bedroom, Clark* used to spend up to 18 hours a day gambling, his world distilled to the spinning reels and flashing lights of online betting apps.

What began as casual wagers – just a few hundred pesos here, a thousand there – quickly escalated. One day, Clark placed a 7,000-peso (US$120) bet that, in a dizzying stroke of fortune, ballooned into 1.7 million pesos (US$30,000).

With that huge win, he thought his luck had changed. Instead, it marked the beginning of a spiralling addiction that highlights the urgent, unaddressed crisis of online gambling gripping the Philippines.

Clark, who is employed in the business process outsourcing sector and works remotely, found himself betting between tasks. “My productivity really suffered. I only took breaks just to eat or sleep,” he told This Week in Asia.

Clark’s relationship with gambling began early, with bets on off-track horse racing as a teenager. Physical casinos came next, but the thrill soon gave way to paranoia: he feared being watched and marked as a high-roller.

“Although I wanted to go back, I was getting paranoid that they were monitoring me through the cameras and knew that I was a big spender. That’s why I transitioned to gambling online,” he said.

The digital world offered Clark what he craved: anonymity and convenience. “On payday, I would automatically transfer all of my funds to my e-wallet to top up for gambling portals and apps,” he recalled.

But the ease of access soon became a trap. Between 2021 and 2023, Clark accumulated millions of pesos in debt – owed to banks, credit card companies, even friends and family.

“There was a time when I had no money in my account, but one of my credit card companies offered a 500,000-peso loan,” he said. “Initially, I was going to use it to pay some debt. I set aside half of it for my bets. I ended up losing everything.”

Clark is far from alone. He is part of a fast-growing group of Filipinos battling addiction to online gambling. While the Philippine government has not released any official figures on gambling addiction, a 2023 survey by Capstone-Intel found that 64 per cent of Filipinos had tried online betting, with 66 per cent of bettors aged 18 to 40 and 57 per cent from 41 to 55.

The industry’s growth has been astounding. Last year, the Philippines recorded 410 billion pesos (US$7 billion) in gross gaming revenue, with the state-owned Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation predicting this could hit up to 480 billion pesos by year’s end.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

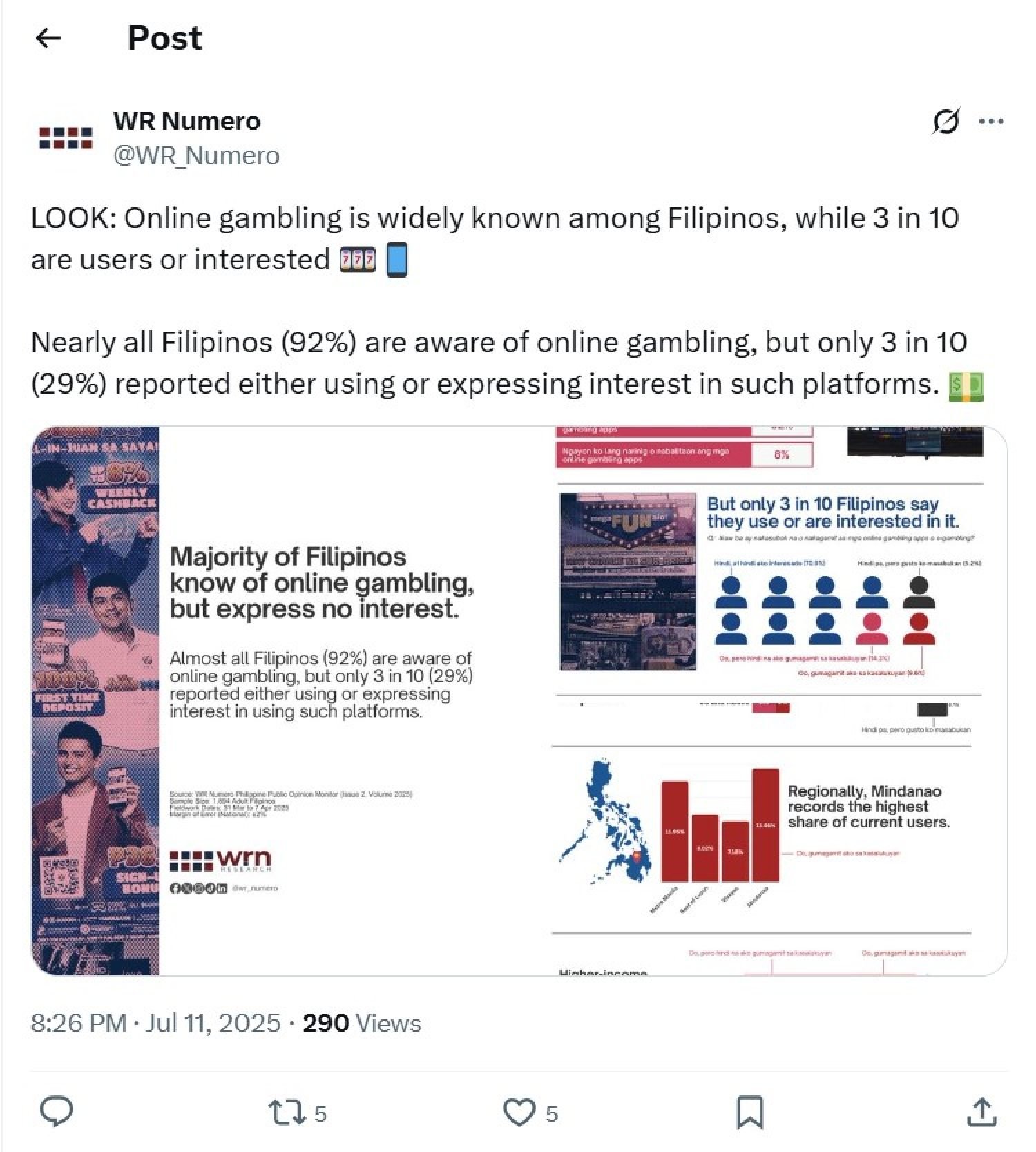

A recent survey by pollsters WR Numero found that nearly one in three Filipinos, or 29 per cent, had either gambled online or wanted to try.

‘Worse than Pogos’

But as the nation’s appetite for online betting swells, its leadership remains largely silent. On Monday, President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr delivered a populist-tinged State of the Nation Address, pledging a raft of improvements in welfare and infrastructure and vowing to tackle corruption.

Conspicuously absent, however, was any mention of online gambling – a silence that has angered lawmakers and advocates alike, as public concern mounts over what many now call a “silent epidemic”.

Opposition Senator Risa Hontiveros, who has introduced legislation to ban e-wallets from connecting to gambling platforms, called the omission a “missed opportunity”. Fellow Senator Joel Villanueva likewise expressed his disappointment.

“We’re talking about [social] ills that it’s bringing to our people, destroying the moral fibre of our society. It’s becoming a national crisis. It’s worse than Pogos,” Villanueva said, referencing the now-banned Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators. He pointed to a police officer arrested in 2021 for robbing a remittance store to feed his gambling habit and a teenager detained after racking up half a million pesos in debt betting on online cockfighting.

“These evil effects cannot be bought off by money, so this needs to end for good,” Villanueva told local reporters.

Senator Bong Go has described online gambling as a “growing menace to public morality, family stability, and financial security”, warning in a statement that the social costs had become “too large and deep”. He stressed the need for urgent action, regardless of the president’s silence.

Presidential press officer Claire Castro told local media on Tuesday that Marcos was still assessing the impact of online gambling and would refrain from comment until the issue had been “thoroughly studied”.

But for those on the front lines of addiction, the president’s silence speaks volumes.

“That can indicate that maybe there’s a business interest in the online gaming environment, which is why they could not tackle it all,” said Jon Ty, founder and director of Bridges of Hope, a nationwide network of 15 rehabilitation centres.

Reagan Praferosa, director of the support group Recovering Gamblers of the Philippines, echoed this sentiment, noting the proliferation of Philippine Inland Gaming Operators (Pigos) – local casinos that have stepped in as Pogos exited the market.

“The greediness is already there,” he told This Week in Asia. “We know who is behind these [Pigos], and we don’t care. We only care about the suffering addict.”

Both Ty and Praferosa believe the government has missed an opportunity, not just to acknowledge the crisis, but to press gambling operators to institute responsible gaming programmes.

National crisis

Praferosa, himself a reformed gambler, has seen the devastating reach of online betting. He said the accessibility, the relentless promotion by influencers and the lure of “free credits” had made gambling omnipresent.

“People are always on their phones. The minimum bet is so low – you can place a bet even for just one peso. Gamblers have also lost their safe spaces,” he said.

“As casino players, we would have comfort and refuge in our home where we’re safe. But now, you can be triggered [to bet] even in your own home. You sacrifice even sleep just to play.”

Before the pandemic, Praferosa said he received an average of three calls a day for help with online gambling. In the past year, that number has surged to 20. His support group now meets more often – and the demographics are changing.

“Before the pandemic, we were dominated by men. But lately, we have become dominated by housewives and children. There has been a sudden change, especially in 2023 and 2024. Our attendees are getting younger,” he said, linking the shift in part to the rise of online cockfighting and betting apps during the Covid era.

Two years ago, 60 per cent of Praferosa’s 200 support group attendees sought help for online gambling and 40 per cent for physical venues like casinos, he said. Last year, among 400 participants, a staggering 90 per cent needed intervention for online gambling and just 10 per cent for casinos.

Ty, who fields up to 10 calls a day from desperate families, said his team was “already on red alert on this situation progressively getting worse”.

Both Ty and Praferosa have witnessed the severe mental health consequences of addiction: crushing debt, family breakdowns and the corrosive effects of shame and stigma.

Among Ty’s cases was a man in his thirties who resorted to robbing Jeepney drivers to cover his losses. Praferosa’s experience is even more sobering: he has lost four hotline clients to suicide.

“The police would call me because my hotline was the last they called,” he said. “They couldn’t bear the debt and shame they caused their families.”

Praferosa urged the government to establish a gambling board to regulate online access and protect vulnerable players. Ty, who favours an all-out ban, called for lawmakers to consult with frontline professionals and advocates to ensure policies were effective.

“If we’re the biggest network in the country and no one reached out to us, it’s less likely they’re reaching out to others,” Ty said. “I hope they’re talking to an expert and doing something about it.”

*Name changed to protect identity