Will Bangladesh veer from its India-China middle path?

India’s recent aid gesture reflects resilient ties with Bangladesh, as analysts say fears that Dhaka will pivot towards China are misplaced

When a Bangladesh air force jet slammed into a school on July 21, killing 31 people, India was the first country to respond – dispatching a team of specialist doctors, nurses and emergency medical equipment.

Their swift arrival earned public praise from the head of Bangladesh’s interim government, Muhammad Yunus, and sparked cautious optimism that a thaw may be possible after months of strained ties between the neighbours.

“These teams have come not just with their skills, but with their hearts,” Yunus said. “Their presence reaffirms our shared humanity and the value of global partnerships in times of tragedy.”

The gesture was widely seen as a reaffirmation of the enduring ties between India and Bangladesh – ties that have frayed in recent months amid shifting political winds in Dhaka and rising Indian unease over the interim government’s perceived tilt towards China.

Since the ousting of long-time leader Sheikh Hasina in a student-led uprising in August last year, the Yunus administration has sought to recalibrate its foreign relations, prompting speculation over Beijing’s growing influence just across India’s eastern border.

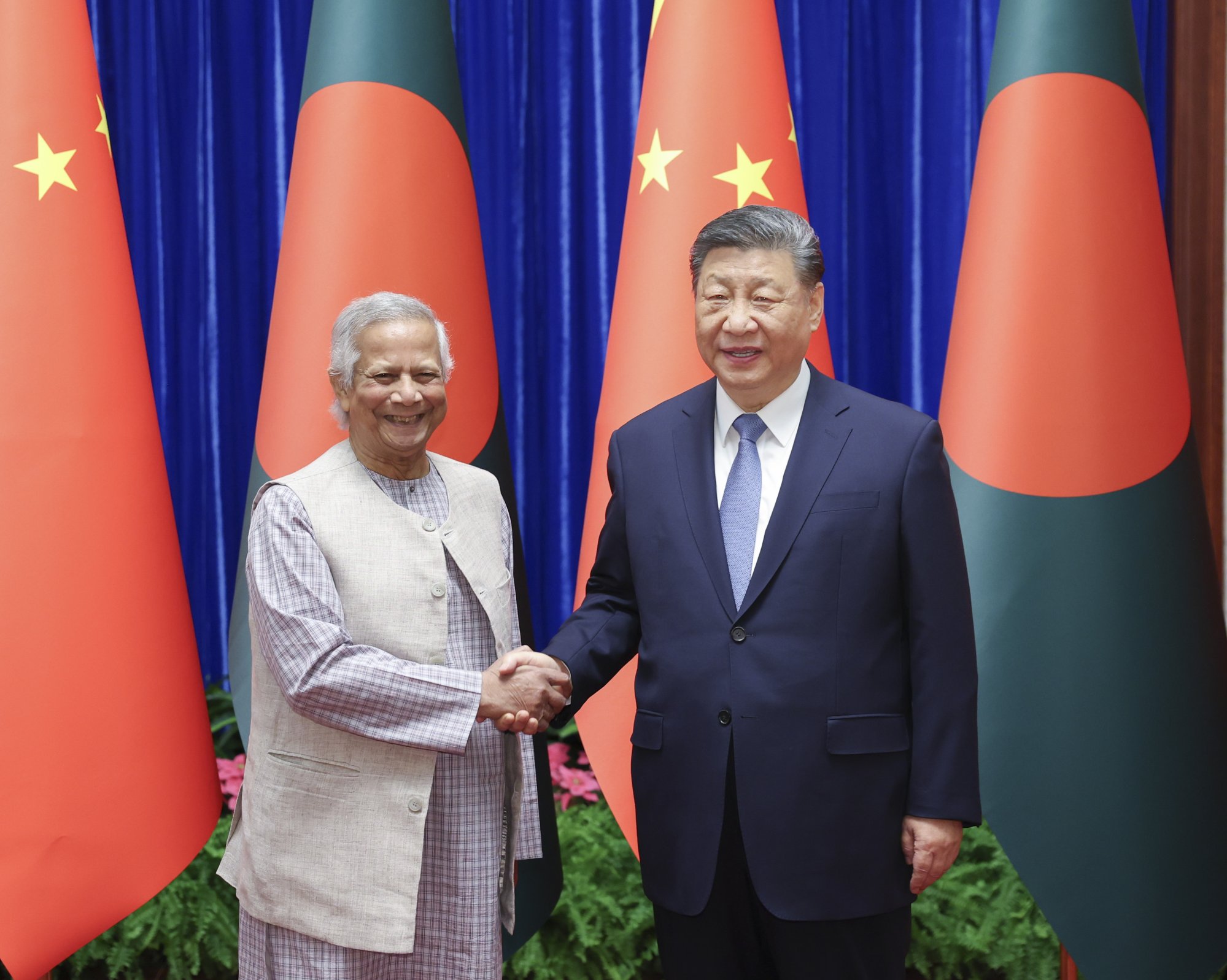

Those concerns intensified following Yunus’ visit to China in March this year, prompting speculation that Chinese-led infrastructure projects could be developed near Bangladesh’s Teesta River, close to India’s northeastern border.

About a month before her regime was toppled, Hasina had publicly voiced her preference for India over China for a US$1 billion Teesta River project. However, the political transition has cast uncertainty over the fate of such projects.

Sreeradha Datta, a professor of international relations in India’s O.P. Jindal Global University, noted that Dhaka had been working with Beijing even during Hasina’s regime and had secured funding for a number of projects.

“The difference is when China was working closely with Hasina we knew it was not going to pose any security concerns for us,” she said, adding that the regime change in Bangladesh fuelled concerns in India that Yunus would allow China to do anything from Bangladesh’s soil.

“I think this apprehension is misplaced because at the end of the day the Yunus government is an interim one. I don’t think any elected government will not want to do business with India,” she said, noting the countries’ geographical proximity.

Indian media had reported in April that China could build an airfield in Bangladesh’s Lalmonirhat district along India’s eastern border, close to an area known as India’s Chicken’s Neck corridor – a narrow strip of land linking the northeast region to the rest of the country.

Chinese companies could think of setting up manufacturing facilities in Bangladesh for sectors such as automobiles, while Bangladesh might step up exports of agricultural products such as jackfruits, mangoes and marine products by way of expanding business relations, she said.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

According to Datta, the likelihood is that these projects may be established for their commercial viability, although there has been little evidence about China setting up an airbase at Lalmonirhat probably because it lacks economic potential.

Analysts say New Delhi’s concerns have understandably been piqued because of the location of Lalmonirhat.

The space was used as an aeronautical education institute and for training purposes under the previous government, but Bangladesh’s recent plans had turned towards making it a fully functional air force facility, said Priyajit Debsarkar, a London-based author who writes on South Asia.

If China took responsibility towards regeneration and redevelopment of the land, then it could have strategic implications for India, particularly if Chinese hardware or equipment was installed in the future, he added.

Bangladesh has also been trying to recalibrate its international trade relations in the face of steep US trade tariffs on its mainstay garment exports, but the country may not have a ready alternative despite its pivot towards China, analysts say.

Bangladesh’s Foreign Affairs Adviser Touhid Hossain had in June denied speculation that the country was aligning towards any political bloc with China and Pakistan after holding talks on the sidelines of a China-South Asia Exposition in Kunming.

Analysts say Dhaka is likely to be conscious of walking a middle path between China and India, as it needs support from both countries in the midst of a volatile global trade environment.