Beijing promised Manila billions in development aid. Why did it fall so short?

New study shows China disbursed US$700 million out of a promised US$30.5 billion, with analysts blaming political tensions for the gap

China pledged US$30.5 billion in development aid to the Philippines between 2015 and 2023 – the most for any Southeast Asian country – but only a sliver of that funding ever arrived, according to new data from an Australian think tank report.

Of the total pledged, just US$700 million was actually disbursed – a shortfall analysts attribute to derailed infrastructure projects, changing political winds in Manila and rising tensions with Beijing. These factors have not only stalled flagship ventures under the Belt and Road Initiative but also cast doubt on the long-term viability of Chinese development finance in the region.

The report by the Sydney-based Lowy Institute, released on Sunday, found that while the Philippines received the highest total commitment from China among Southeast Asian nations, it ranked near the bottom in actual disbursements.

Indonesia, by contrast, received and spent US$20.3 billion out of the US$20.7 billion Beijing had pledged, mostly on energy and transport projects.

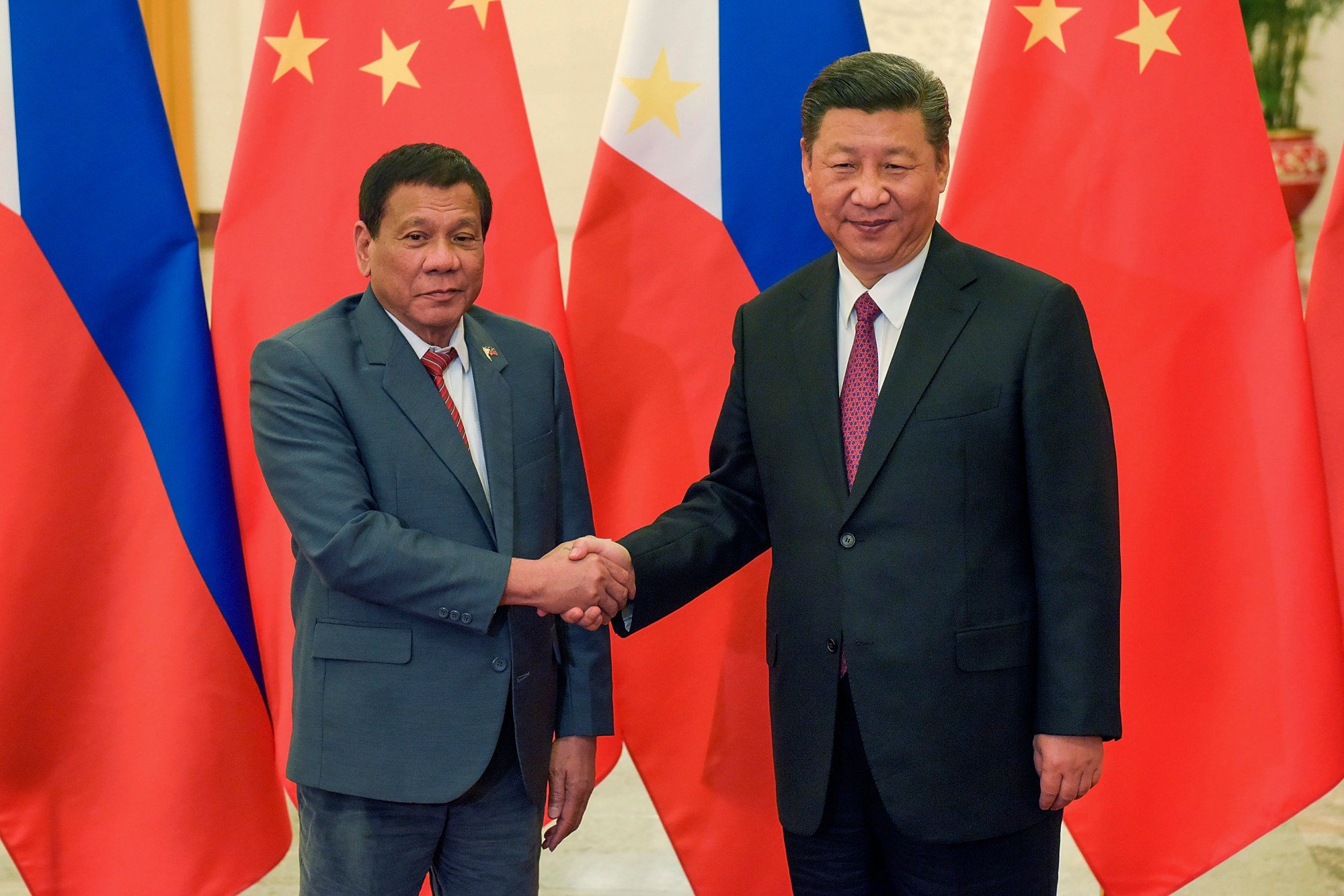

The bulk of China’s pledged financing to the Philippines was made during the administration of former president Rodrigo Duterte, who held office from 2016 to 2022 and pursued closer ties with Beijing through a wave of high-profile infrastructure agreements.

But many of those projects never materialised, and under President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr, engagement with China has slowed considerably.

“The lack of follow-through on China’s infrastructure promises in the Philippines is largely a political story,” Grace Stanhope, a research associate at the Lowy Institute overseeing the research, told This Week in Asia.

“There was much more ambition in the relationship and several large megaproject deals were signed” under Duterte, she said. “But under Marcos, there is much more caution and very low levels of new commitments.”

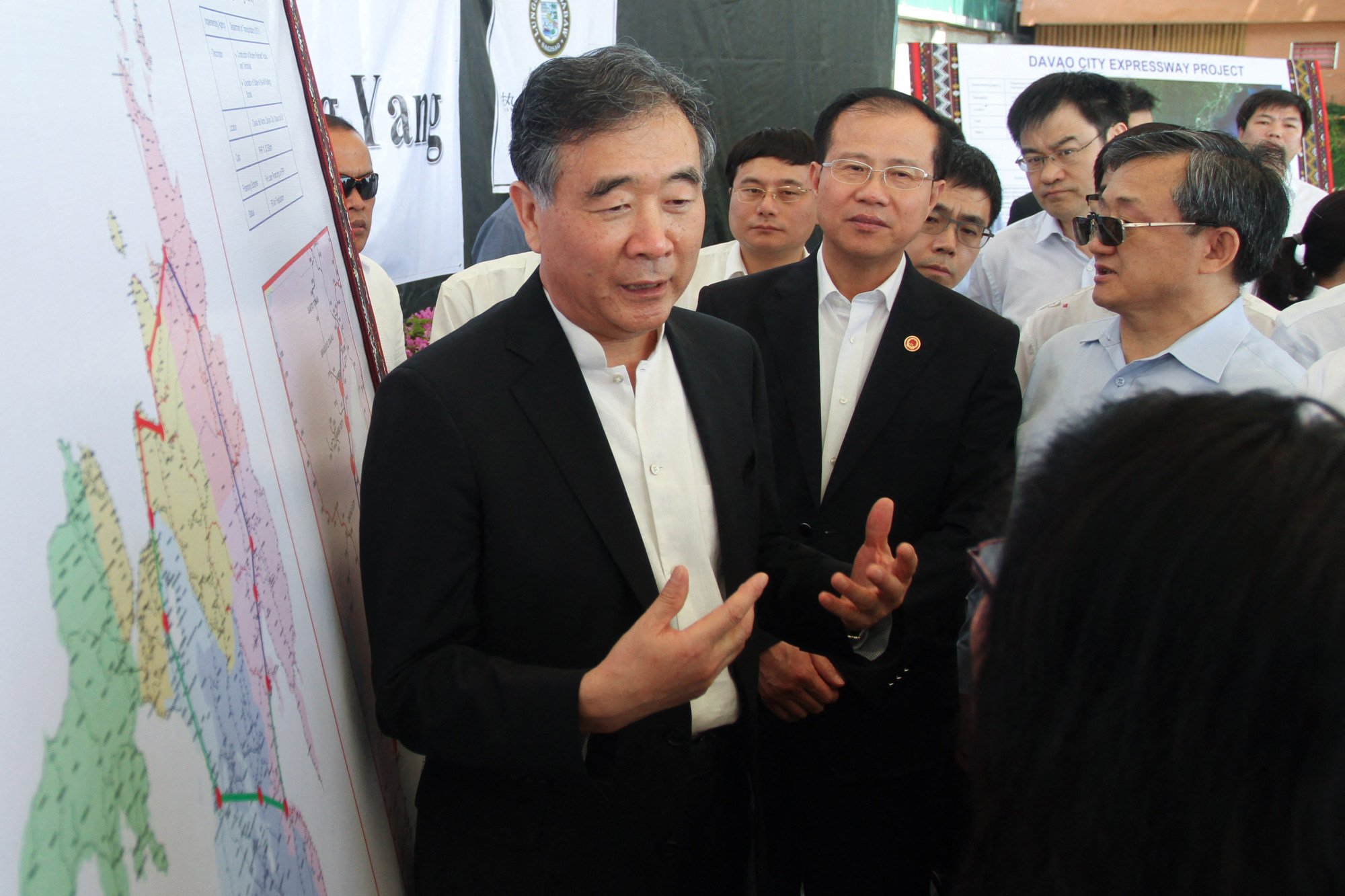

Three major Chinese-backed railway projects were cancelled in 2023, amid rising maritime tensions between Manila and Beijing over their overlapping territorial claims in the South China Sea.

These included the proposed Mindanao Railway, which was supposed to have broken ground in 2022. That same year, the Philippine Department of Transportation reported that China had failed to respond to repeated follow-up requests on funding.

The Department of Finance later informed the Chinese embassy that the Philippines was “no longer inclined” to pursue financing for the railway, following remarks from a senior Chinese economic official who cited “geopolitical factors” as a constraint.

Two other railway projects – a 380km line connecting Laguna to Bicol and a 71km line linking Subic Bay to Clark – also failed to take off. The latter has since been incorporated into the Luzon Economic Corridor, to which the US pledged $15 million in investments during Marcos’ visit to Washington earlier this week.

Of the many belt and road-linked proposals, only one – the 4.5 billion peso Chico River Pump Irrigation Project – was completed. China also donated 1 billion pesos (US$19.5 million) in defence equipment.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

Other infrastructure projects such as the Kaliwa Dam “will continue to generate disbursements in coming years, but we don’t really expect to see much growth”, Stanhope said.

Chester Cabalza, president of the Manila-based think tank International Development and Security Cooperation, said ongoing tensions in the South China Sea had limited the scope of economic cooperation.

“China will sustain its absence or declining trade in exports and imports with the Philippines under the Marcos administration due to the ongoing maritime security dilemma,” he told This Week in Asia.

Yet others argue that the shortfall in Chinese funding cannot be explained by geopolitics alone.

“The failure in the delivery of funding from China goes beyond a fundamental deterioration in Philippines-China relations,” said Matteo Piasentini, a geopolitical analyst and international relations lecturer at the University of the Philippines.

“Make no mistake: the effective delivery of development assistance is always complex and contentious. It depends on multiple factors, including bureaucratic coordination, budgetary constraints, and more,” he told This Week in Asia.

He noted that other factors could include the Philippines’ deep-rooted ties with alternative donors such as Japan, and the possibility that “the Philippines jumped late on the bandwagon of China’s charm offensive in Southeast Asia”.

“I believe the Philippines has, on several occasions, demonstrated its willingness to engage in dialogue. However, the current leadership perceives the risk of external influence or economic coercion to be too great at this time,” Piasentini added.

Tariff trouble

The study comes at what the report described as an “uncertain moment” for Southeast Asia, whose “highly successful export-driven economic model is at risk” from US President Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs and declining foreign aid from major Western donors.

The Philippines, a key US ally, secured a modest tariff reduction following Marcos’ Washington visit, with Trump agreeing to lower duties on Philippine exports from 20 per cent to 19 per cent.

Although Manila seems to be “relatively well-protected from the tariffs” compared to other Asean member states, Stanhope said Trump’s punitive levies continued to threaten economic growth and development, which would further be compounded by aid cuts.

The Philippines’ largest finance providers are multilateral development banks such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. Stanhope said there were no signs these banks would decrease spending, but cautioned that “those announcements could be coming, if the countries cutting their aid budgets also reduce contributions to these banks”.

Piasentini, meanwhile, said tariffs and investment were not necessarily linked to trade, adding the Philippines “still has the opportunity to strengthen bilateral ties with multiple regional and extra-regional partners, despite looming tariffs from the US”.

Cabalza told This Week in Asia that Trump’s tariff strategy amounted to a “salami-slicing trade-off in the region” – referring to a tactic of offering incremental, selective benefits to divide or pressure rivals – which he said had further polarised the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), pushing member states to choose between aligning with the US or China.

Despite the fallout from Chinese funding, the Philippines’ economy has remained resilient and could withstand a “frustrating 19 per cent tariff from an ally”, according to Cabalza, who suggested Manila focus on “Japan and other like-minded countries [in bringing] more funding into the country”.