In Japan, fears grow of Aum Shinrikyo death cult’s revival

A woman widowed by the 1995 Tokyo sarin attack warns the founder’s son is poised to rebuild the notorious cult and its deadly ambitions

The widow of a man killed when followers of the Aum Shinrikyo cult released sarin gas on the Tokyo subway system in 1995 has warned that a son of the founder of the apocalyptic religious group intends to resurrect its operations and ambitions.

Shizue Takahashi also cautioned that public memory of the attack – which killed 14 people and left 5,000 others needing treatment for exposure to the nerve agent – is fading in Japan, making it easier for Shoko Asahara’s son to reassert control and rebuild the group.

“Asahara’s second son was born and raised within the Aum Shinrikyo cult and has been indoctrinated during that time by his father’s teachings,” Takahashi told This Week in Asia.

“Rather than being encouraged by Asahara’s loyal believers to become the next leader of the cult, I believe he personally desires to seize power and rebuild the organisation,” Takahashi said.

“If he becomes as powerful within the cult as his father was, I believe he will try to expand it and create a new version of Aum Shinrikyo.”

Takahashi’s warning comes after Japan’s Public Security Intelligence Agency reported this week that Asahara’s second son, a 31-year-old who has not been named, has emerged as the “second-generation guru” and leader of Aleph, the group that was formed after Aum was forcibly disbanded.

The agency announced on Tuesday that the man had been heading Aleph’s operations for about a decade, supported by Asahara’s widow, 66-year-old Tomoko Matsumoto. The son’s elevation is in accordance with the wishes of Asahara, who identified him as his successor after he was arrested in 1995.

In its latest report into the status and activities of the group, the agency confirmed that it has 20 facilities around Japan and an estimated 1,190 followers.

Agency officials also confirmed that an inspection of a flat in Saitama prefecture, north of Tokyo, where Matsumoto and Asahara’s son presently live, led to the discovery of tens of millions of yen in cash. The agency has been unable to determine where the funds came from and what they were likely to be used for, although it requested in its report that the cult not be permitted to buy additional properties in Japan.

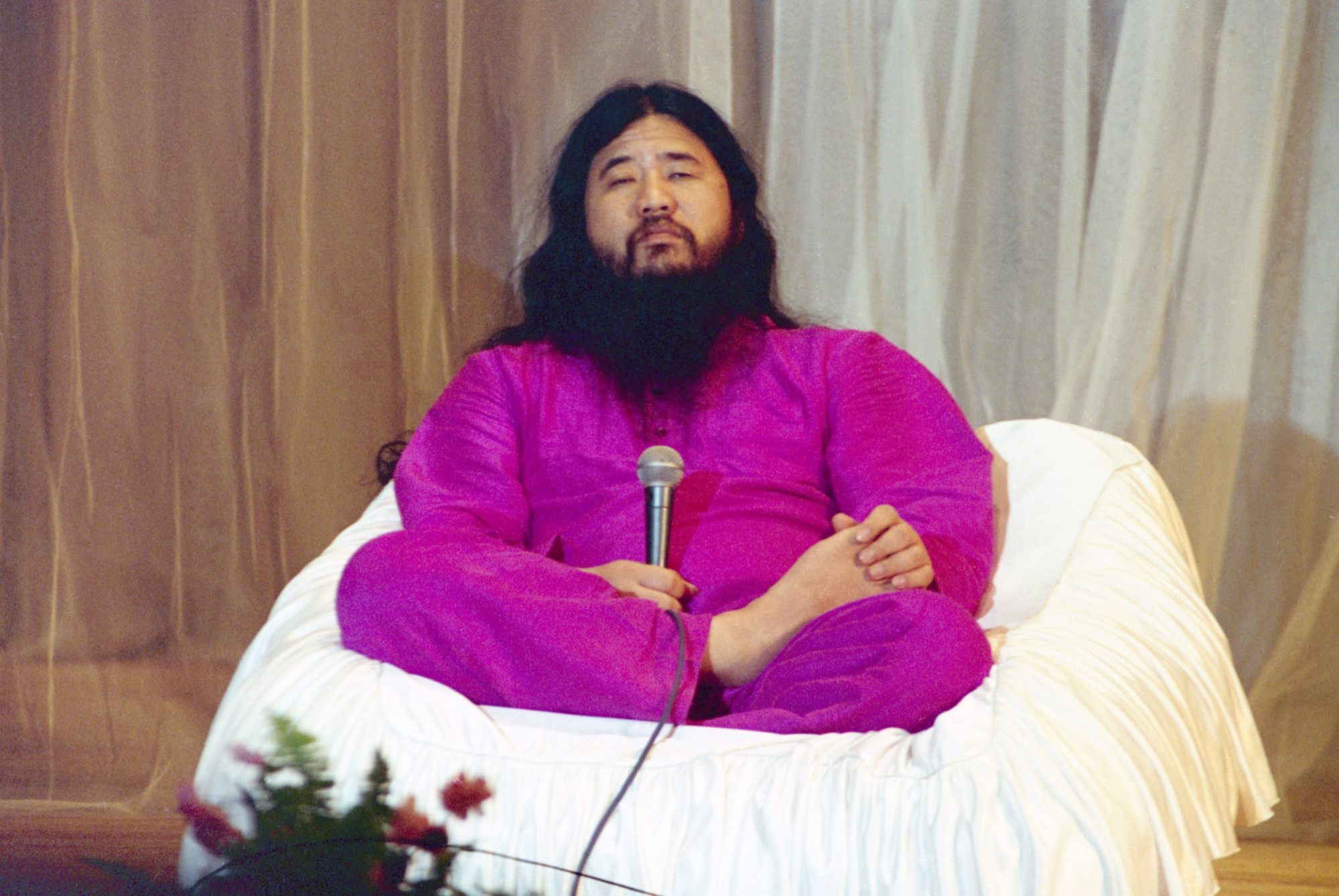

Founded by the partly blind Asahara in 1987 as a yoga school, Aum grew by appealing to socially awkward members of Japanese universities. Soon, the group became more aggressive in its ambitions, standing in national elections but failing to achieve a broader following.

Frustrated by the group’s failure to gain political support, Asahara began plotting to seize control of Japan. In remote compounds across the country, engineers and chemists recruited from top universities developed weapons, including machine guns and chemical agents.

In 1994, the cult tested sarin gas at the home of a judge in Matsumoto. The following year, aware that authorities were preparing a crackdown over Aum’s involvement in several crimes – including the murder of a lawyer and his family – the group carried out the sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway during the morning rush hour.

Dozens of Aum members were charged with crimes, but 13 individuals were ultimately sentenced to death. Asahara and 12 followers were hanged in July 2018.

Takahashi’s husband, Kazumasa, was assistant stationmaster at Kasumigaseki, one of the stations that cult members targeted because it is used by bureaucrats at Japan’s ministries and government agencies. Responding to reports of passengers collapsing aboard a stationary train and on the platform, he picked up a plastic bag of sarin that had been deliberately pierced to remove it from a carriage, but collapsed and died within minutes.

Today, Shizue Takahashi is a leading member of the Tokyo Subway Sarin Incident Victims’ Association and is demanding that more be done to halt the activities of Asahara’s remaining acolytes.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

“The agency can monitor Aleph through inspections, but it lacks the authority to investigate its activities. The police and other agencies need to share all the information that they have with the agency and compel Aleph to disclose everything about its activities and the assets that it is hiding,” she said.

Takahashi noted that the Supreme Court had in November 2020 ordered Aleph to pay more than 1 billion yen (US$6.85 million) to the organisation representing Aum’s victims.

Aleph reported having 1.3 billion yen in assets at the time of the ruling, but that amount quickly dwindled and the group soon claimed it had only 10 million yen available, Takahashi added.

“The reason it continues to hide its assets is to avoid paying compensation to the victims’ organisation,” she said. “If the money found in the flat in Saitama is cash being hidden from the authorities, then I and the rest of the families will be outraged.”

Ultimately, Takahashi is calling for Aleph and two other splinter groups, Circle of Light and the Yamada Club, “to be dissolved as soon as possible”.

“The crimes committed by Aum are fading from people’s memories and younger people lack a sense of crisis,” she said. “I strongly believe that the younger generation is vulnerable to the threats posed by these groups today.”