‘Grooming’: uproar over student-teacher ‘romance’ forces K-drama off the air

The TV drama in which a teacher falls for her 12-year-old pupil was meant to arouse curiosity. Instead, it ignited a firestorm of criticism

Barely a week after its unveiling, a South Korean television drama centred on a forbidden romance between a teacher and her 12-year-old student was cancelled, following a torrent of public outrage that laid bare the uneasy intersection of storytelling, social responsibility and child safety in the nation’s booming media industry.

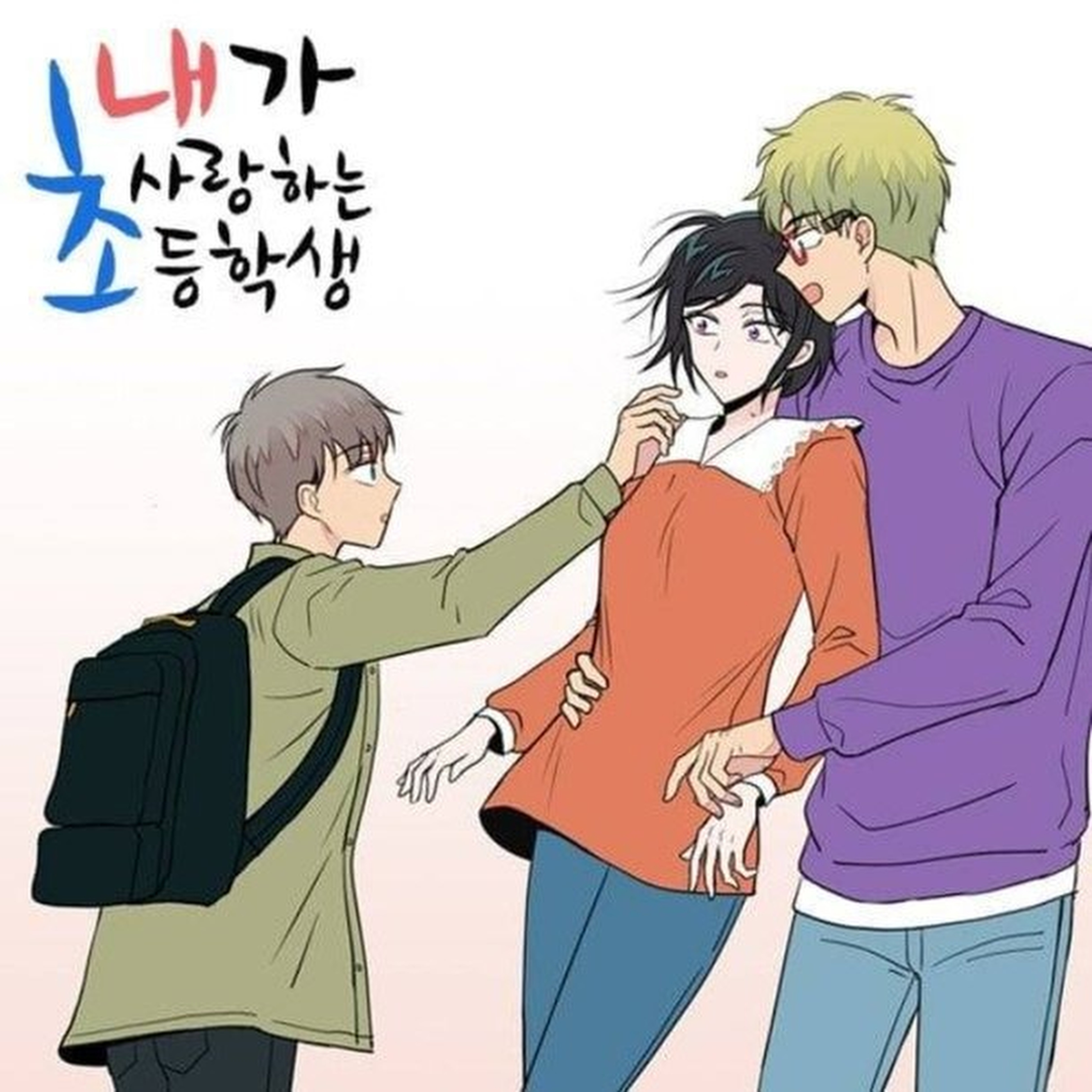

The series – tentatively titled The Elementary School Student I Love – was to be based on a webtoon of the same name and had only just been announced in late June when it was met with immediate and overwhelming condemnation. Within days, educators, civic groups and ordinary viewers had united in calls for its cancellation, denouncing the premise as a dangerous romanticisation of abuse.

By July 4, production company Meta New Line had bowed to public pressure, saying in a statement it would “suspend the production and planning” of the drama, citing “changing social sensitivities”.

At the centre of the storm was a plot in which a woman in her twenties developed romantic feelings for one of her students – a storyline many critics likened to a glorification of grooming.

Far from being an isolated artistic misjudgment, the controversy has spurred a broader reckoning within South Korea’s thriving webtoon and television industries, raising urgent questions about where the line should be drawn between storytelling and social harm, especially in an era when Korean content is finding a global audience.

Normalising the ‘unacceptable’

One of the most forceful condemnations came from South Korea’s largest teaching union, which accused the show’s creators of “idealising” what should have plainly been recognised as abuse.

“[A teacher] abusing their status to share private emotions with a student and developing that into a romantic relationship is not romance or fantasy, but a clear idealisation of sexual grooming,” the Korean Federation of Teachers’ Associations (KFTA) said in a statement on July 1.

“Attempts to sexualise children under the guise of creativity and artistic originality can never be justified.”

The union warned that such content would “undermine the values of child protection, damage trust in the teaching profession, and potentially cause harm to children and adolescents”.

It’s shocking that a storyline like this was even considered for broadcastPark Byung-ha, Korean educator

Among educators, the sense of alarm was readily apparent. “It’s shocking that a storyline like this was even considered for broadcast,” said Park Byung-ha, a 25-year-old teacher of physical education in Seoul.

“Content like this is dangerous because it risks normalising unacceptable relationships. A teacher’s feelings toward a student should never go beyond care and responsibility.”

Yet while the public condemnation was swift, some industry insiders noted that stories involving relationships between adults and adolescents have long lingered in the shadows of South Korean webtoons – albeit confined to niche digital spaces with limited readership.

“With webtoons, readers choose what to see,” said Wendy Kim, a 26-year-old webtoon illustrator in Seoul. “You have to search for these story subjects, and only people with that taste usually find them. It’s different from dramas, which are broadcast widely to the general public.”

Veteran comic critic and columnist Seo Chan-hwe agreed that such narratives once existed quietly on the fringes. “This material used to be for a closed readership,” Seo said. “What was underground has now surfaced to a broader audience.”

The trope of teacher-student romances was not new, he argued, having appeared for decades in both Korean and Japanese comics – but he said the public’s understanding of its dangers had evolved. “It’s practically a formula … I don’t want to blindly condemn the author or the producer. They were lazily repeating what had been done before,” he said.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

“In the past, many turned a blind eye. Now, everyone understands the inherent danger in depicting such a power-imbalanced relationship. Today, we recognise it for what it is: [sexual] grooming.”

Seo dismissed the notion that flipping the gender of the adult and child typically seen in such stories made it less problematic.

“It’s still inherently patriarchal,” he said. “It caters to a particular fantasy young men might have towards older women … but in reality, most grooming cases involve adult men and young girls. So even when the gender is flipped, it depicts real-world violence.”

At its core, the issue was the fundamental hierarchy embedded in the teacher-student relationship, he sai. “It’s about trust, power, and the inability of a child to give meaningful consent.”

Culture clash

The uproar has triggered renewed calls for stricter oversight of South Korea’s booming media industry, which churns out thousands of titles annually for domestic and international audiences, often with scant formal regulation. As K-dramas and Korean webtoons achieve unprecedented global reach, the question of how these stories reflect or shape social norms has never felt more urgent.

“It’s different from platform to platform, but sometimes, almost 80 per cent of content on a site is explicit,” said Kim, the illustrator, referring to webtoon platforms. “There’s often no editorial guideline or ethical review process involved.”

Civic groups have long called for tougher regulations on the webtoon industry. In 2020, an online petition protesting against a comic depicting unethical behaviour attracted more than 130,000 signatures.

These demands were renewed following The Elementary School Student I Love controversy, with the country’s second-largest teachers’ union – the Korean Teacher and Education Workers’ Union – calling for government regulation of the webcomic sector.

In the past, many turned a blind eye. Now, everyone understands the inherent dangerSeo Chan-hwe, veteran comic critic

But Seo, the columnist, cautioned against censorship. “All forms of expression should be protected,” he argued. “But creators and producers must be prepared to face public criticism.”

Instead, he called for a more nuanced debate. “We need a forum, facilitated by traditional media, where artistic freedom and social responsibility can be debated in a healthy way. If people think a subject is not suitable, they will not watch or read it, and that will naturally resolve clashes.”

The decision by Meta New Line to halt production of the series was welcomed by teachers’ unions as a rare example of showrunners heeding public sentiment.

“It is a suitable decision that accepts the demand of the 500,000 education workers, protects children, and recovers the honour and trust of teachers,” said the KFTA in a statement.

“We will continue to respond [to such developments] so that the relationship between the teacher and student is not distorted [for entertainment], and so that non-educational and unethical content that makes fun of education is not produced,” added KFTA chief Kang Joo-ho.

For educators like Park, the show’s cancellation felt like a rare boundary being upheld in a rapidly shifting culture.

“This isn’t just about one show,” he said. “It’s about whether we as a society are willing to stand up for the rights and safety of children, even in our entertainment.”