Australia juggles its China trade needs with Philippines defence ties

While seeking stable ties with its largest trading partner, Australia must also ‘maintain credibility as a regional stabiliser’, analysts say

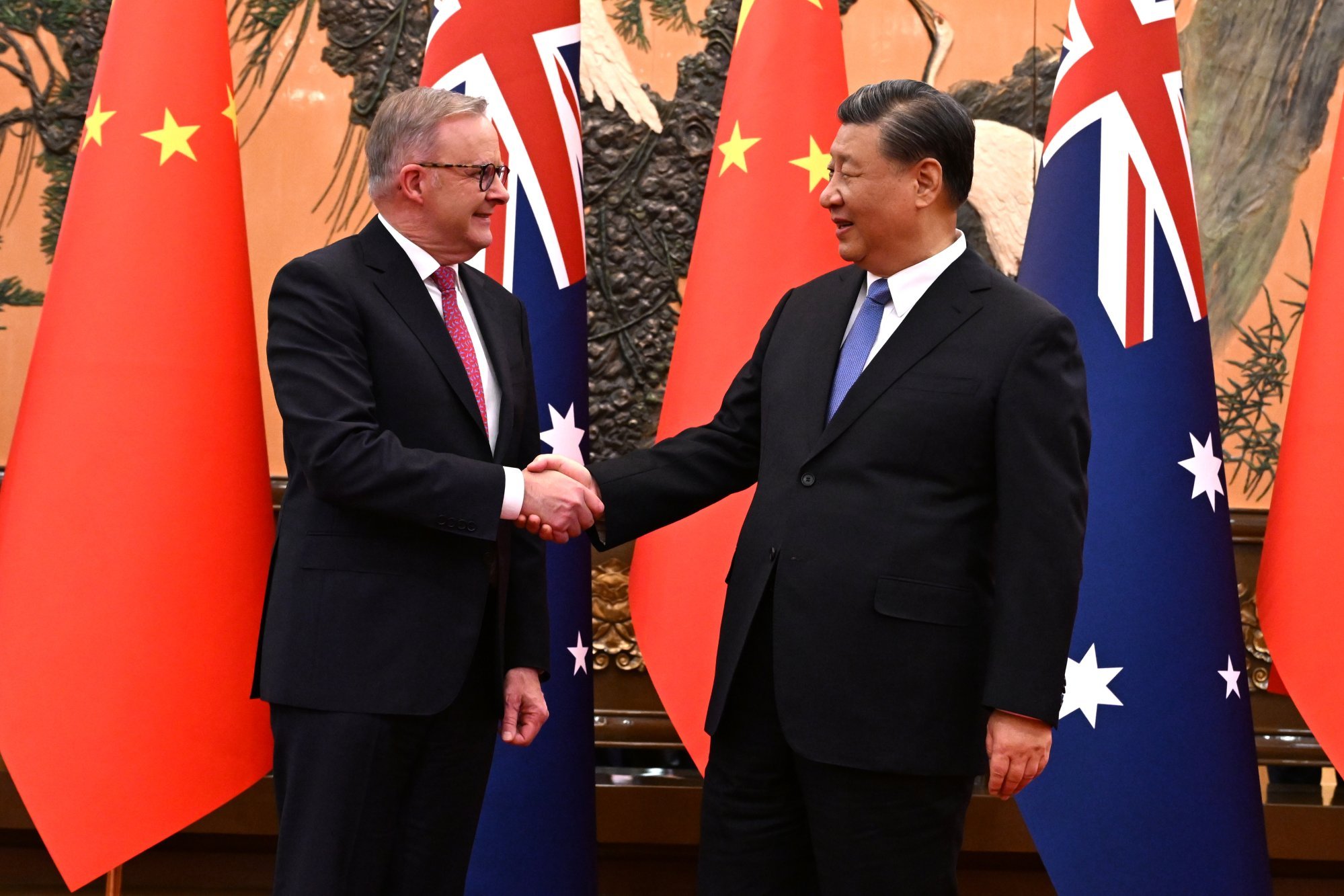

As the Asia-Pacific’s power dynamics continue to evolve and shift, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s visit to China promises to be a test of his country’s ability to walk the fine line between economic self-interest and strategic resolve.

His trip, which began on Saturday, unfolds against the backdrop of Australia’s deepening security ties with the Philippines, with Canberra stepping up support for Manila’s maritime capabilities and increasing participation in patrols and joint military exercises.

In April, Albanese’s government donated 20 state-of-the-art surveillance drones worth 34 million pesos (US$600,000) to the Philippine Coast Guard, buttressing its maritime domain awareness just days after a near-collision between Philippine and Chinese vessels in contested waters.

The donation was part of a broader civil maritime cooperation programme, encompassing vessel remediation, postgraduate scholarships, operational training, marine protection and maritime law seminars. Australia plans to double its investment in these initiatives to A$11.5 million (US$7.5 million) from 2025 to 2029.

Analysts say these moves reflect the pair’s expanding ties over time. “Australia and the Philippines are set to mark 80 years of diplomatic relations in 2026, with both countries motivated to further enhance the strategic partnership in the years ahead,” said Julio Amador, interim president of the Philippines-based Foundation for the National Interest think tank and founder and trustee of the non-profit policy advisory firm FACTS Asia.

Thanks to a visiting forces agreement signed in 2007 and effective from 2012, “the two countries boast strong defence and maritime cooperation”, Amador said. “Because of this, both have regularly conducted high-level dialogues and military exercises.”

In 2023, Canberra and Manila elevated ties to a strategic partnership, broadening cooperation to include counterterrorism, law enforcement, climate action, education, development and people-to-people exchanges.

Australia is trying to position itself as at least an alternative pillar for development and security cooperation here in Southeast AsiaDon McLain Gill, Filipino geopolitical analyst

“Australia is trying to position itself as at least an alternative pillar for development and security cooperation here in Southeast Asia,” said Don McLain Gill, a geopolitical analyst at De La Salle University in Manila. “While it still has a long way to go to significantly cement its influence in the region, the Philippines is in fact one of its most important anchors.”

The Philippines’ geographic location “is of strategic consequence to Australia”, he added. “The eastern seaboard of the Philippines’ exclusive economic zones along the South China Sea hosts an array of vital sea lanes that are critical to linking Australia and Oceania to the immediate region and to the rest of the world,” Gill said, adding that the shared democratic values between Manila and Canberra positioned the Philippines as a “strategic amplifier for Australia’s regional soft power objectives”.

Australia’s Defence Minister Richard Marles said in June last year that relations with Manila were at “high point”, calling the Philippines “vital for Australia’s capacity building” and describing the country as a bridge for broader engagement with Asean and multilateral regional platforms”.

More than a ‘US sheriff’?

But as Australia deepens its engagement in Southeast Asia and upholds its commitment to the international rules-based order, it risks encountering growing pressure from Beijing.

“Increased pressure from the major powers will be a recurring response to ambiguity arising from middle powers, as it has done with Asean countries,” Amador said, noting that Australia’s defence ties with the US through security groupings such as Aukus and the Quad were seen as provocative by China.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

Tensions flared in February when Australia protested against what it called “unsafe and unprofessional” actions by a Chinese fighter jet towards an Australian maritime patrol over the South China Sea – a claim Beijing disputed.

“The expulsion measures taken by the Chinese side are legitimate, professional and restrained, and China has lodged solemn representations with the Australian side,” foreign ministry spokesman Guo Jiakun said.

On Tuesday last week, Albanese noted in a statement that China was Australia’s largest trading partner – accounting for one-third of its total trade – “and will remain so for the foreseeable future”.

“We will continue to patiently and deliberately work towards a stable relationship with China, with dialogue at its core,” he said.

The Australian prime minister’s state visit, through Friday, is expected to take in Beijing, Shanghai and Chengdu, with discussions on cooperation in AI, green energy and the digital economy.

But negotiations were sure to be “nuanced with geostrategic implications”, Amador said.

“Australia’s pursuit of economic interests with China may temper its security posturing,” he said, adding that this delicate balancing act risked producing “incoherent policies”.

Canberra had to “exercise diplomatic finesse in order to maintain credibility as a regional stabiliser, without escalating tensions while pursuing its economic goals,” he said. “Asean partners, including the Philippines, may watch closely how Australia walks this tightrope.”

Meanwhile, Gill argued that despite close ties with Vietnam and Singapore, Australia still “has a long way to go in order to position itself more favourably” in a region where many countries were wary of great-power rivalries.

“The challenge for Australia is to show that it is more than willing to engage with the rest of Southeast Asia in a way that would not make it seem that it is the sheriff of the United States.”