‘More dangerous’ than Pogos: should Philippines ban online gambling?

A surge in online gambling sites and Filipinos hooked on them has led to lawmakers seeking a ban against the ‘silent epidemic’

At the rehabilitation centres run by Bridges of Hope, a recovery network spread across the Philippines, founder Jon Ty is used to seeing the different faces of addiction. For years, clients came seeking help for their abuse of drugs, alcohol or painkillers. Now, most come for something else.

Today, seven in 10 clients treated across the network of centres are battling online gambling addiction – a trend that highlights a deepening crisis in the country, fuelled by a boom in mobile betting apps during the pandemic.

“There’s so much enrolment into our treatment centres when it comes to gambling”, with online betting addiction becoming “an alarming national problem”, Ty told This Week in Asia.

While gamblers who seek treatment from Bridges of Hope come from various backgrounds, Ty is alarmed by the rising number of minors whose families come to the centres for help.

“We have seen many people, mostly the young ones in this generation, since last year, because of mobile apps that are promoting it,” Ty said.

Several lawmakers have already filed bills to regulate the country’s online gambling industry just days into the new Congress, amid increasing public pressure to address the rising cases of gambling addiction, especially among minors.

Senator Juan Miguel Zubiri has called online gambling “a silent epidemic” and proposed an outright ban on all forms of online gambling, including digital betting platforms, mobile applications and websites.

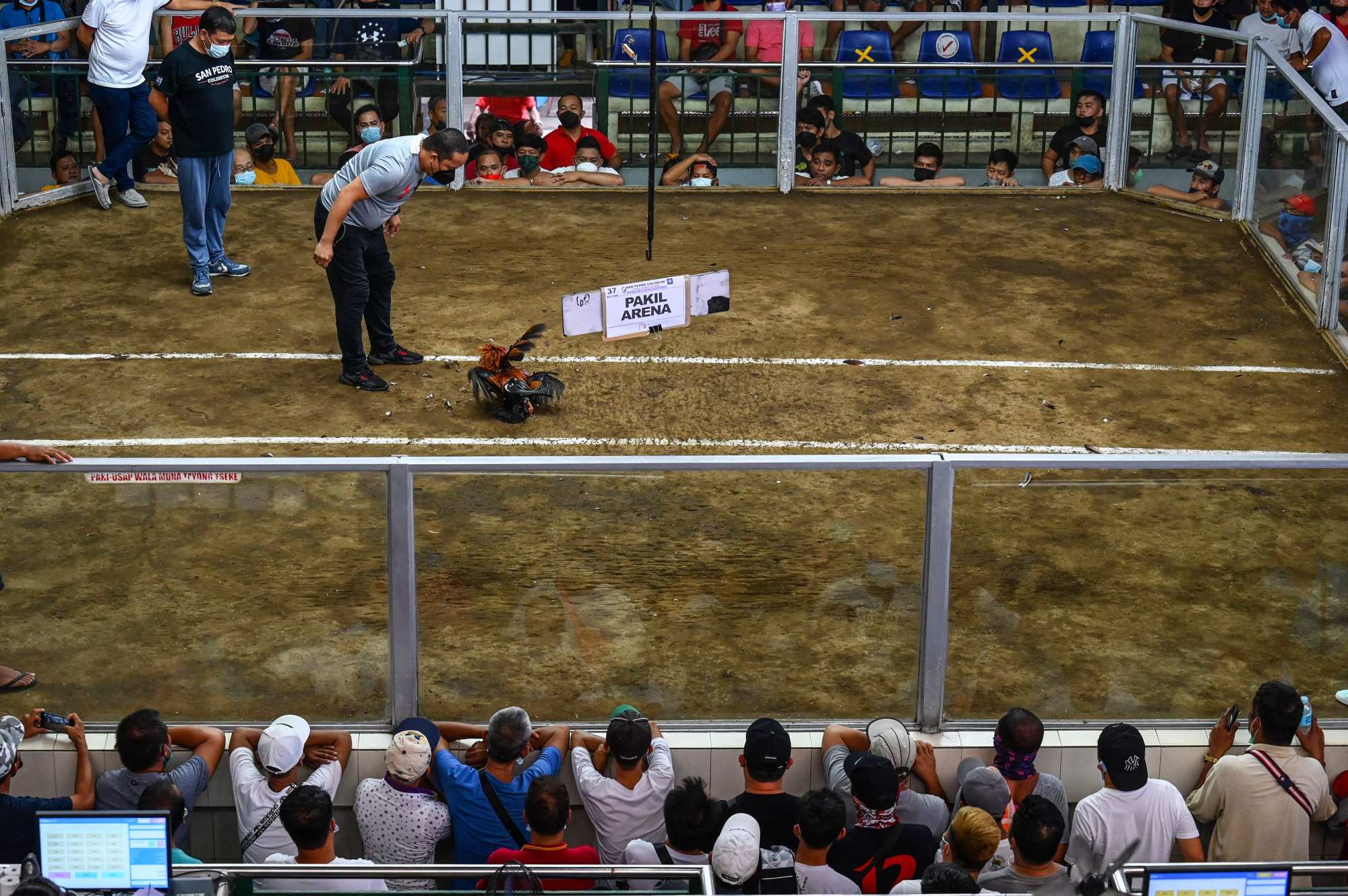

“Let’s not kid ourselves. The face of gambling addiction has already changed. This is no longer someone wasting away at a casino or a cock fighting arena. It now looks like a kid with a phone under the covers at 2am, losing the family’s grocery money on an online casino site,” Zubiri said last week.

Senator Sherwin Gatchalian is seeking stricter regulations for the online gambling industry, including banning betting games through e-wallets and requiring a minimum cash-in amount of 10,000 pesos (US$176).

The Philippines raked in gross gaming revenue of 410 billion Philippine pesos (US$7.2 billion) in 2024, with the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation (Pagcor) projecting this to rise to between 450 billion and 480 billion pesos this year.

Access given by betting platforms had made gambling so “effortless”, leading to rapidly growing cases of addiction, Ty said.

“Unlike before, you physically have to get up, take a shower, ride your car and go to a casino. Now, as soon as you get up and turn on your phone, it’s there. So it’s problematic. It’s alarming to know that everybody – minors and adults alike – is exposed to that,” he said.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

The proliferation of advertisements promoting gambling on social media and its widespread use of celebrities and popular influencers have fuelled its popularity in the country, according to Samuel Cabbuag, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of the Philippines who researches on social media and digital cultures.

“Celebrities and influencers gave face to online gambling and online gambling platforms by allowing their persona to be used as a tool. Because they are popular figures both in digital and traditional media, people look to them as a source of entertainment and information. So by endorsing online gambling, these figures [brought people closer] to the platform,” Cabbuag told This Week in Asia.

Digital gambling platforms had provided an “easier gateway” for people of all ages to engage in gambling through social media, Cabbuag said.

“The free passes, coins, or bonuses packaged in ads to invite people to log in and play are already a great hook. It also gives an illusion of easy money for those who want to earn more than what they have,” he added.

‘More dangerous’ than Pogos

The growing concern over the online gambling boom in the country comes in the wake of other related controversies, such as the ban on Philippine offshore gaming operators (Pogos) and online cockfighting, both of which have been linked to other criminal activities.

Philippine authorities continue to struggle with the fallout of Pogos, which once lured in over 100,000 Chinese and other foreign workers and catered mainly to Chinese customers, as over 9,000 former workers remain at large following President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr’s order last year to close such operations.

Authorities have uncovered links to scam operations and human rights violations during their raids of Pogo facilities.

“The Duterte government’s embrace of Pogos blurred the line between foreign and domestic gambling and prepared the ground for the spectacular rise of e-sabong [live-streamed cockfights]. What was once a sport for wealthy aficionados became a daily pastime for wage earners,” political columnist Randy David wrote in the Philippine Daily Inquirer.

Zubiri said: “We already shut the doors on Pogos for the damage they caused. But an even more dangerous problem has crept into our homes: online gambling that targets our own people.”

Ty attributed the rise in cases of online gambling addiction to the introduction of online cockfighting during the pandemic, when “everybody was trying to create ways to continue their operations using mobile apps”.

“I have encountered minors who are 16, 17, that are into it. Parents promote it because the parents are also gamblers … they did not know down the line how it would affect their children,” he said.

Gambling addictions “hit everybody” across various socioeconomic backgrounds, Ty added.

“Someone who can afford a 2,000-peso stake would probably gamble his savings and then maybe his threshold will be higher than the rank-and-file employees making a minimum salary, but they still gamble. So a 2,000-peso stake would probably be a 200 or 500-peso stake for rank-and-file employees,” he said.

Cockfighting held at various pits in cities, towns and villages is a legal form of gambling in the Philippines. Remote bets placed during live streaming of cockfighting matches skyrocketed in popularity during the pandemic amid strict social distancing measures.

Online cockfighting raked in 7 billion pesos (US$124 million) in 2021, according to Pagcor. The industry was rocked by the disappearance of 30 cock fighters in 2021 and 2022, with a whistle-blower alleging that all of the victims were killed and dumped in Taal Lake, a popular tourist attraction south of Manila.

Amid attempts by lawmakers to impose stricter measures on the gambling industry, Ty expressed fears that regulation – instead of an outright ban – would only allow addiction cases to persist.

“[Online gambling] is too convenient … If it’s too accessible, our kids will be exposed to it, and that’s when harm comes into play. If you leave room there, that little wiggle room will magnify and escalate,” he said.

The general tolerance for gambling in the Philippines had made it difficult to control the industry, Ty said. “In Filipino culture, it’s OK to gamble. [It does not factor] the mental health of people if they get [too deep] into it. They don’t see what we see when people and families suffer.”