Japan dives deep in race for rare earths, stirring a green backlash

While rich mineral deposits promise centuries of supply, critics argue Japan’s deep-ocean venture risks an irreversible ‘race to the bottom’

Japan’s quest for rare earths is about to plunge to unprecedented depths in what could be the most extreme trial extraction ever attempted, accelerating a push to lessen its reliance on overseas suppliers – but at what environmental cost?

The Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology plans to deploy a deep-sea drilling vessel to a site around 100km (54 nautical miles) from Minamitorishima, according to a report in the Nikkei newspaper dated July 1.

The remote atoll is some 1,850km (1,600 nautical miles) southeast of Tokyo and marks the easternmost tip of territory that Japan claims.

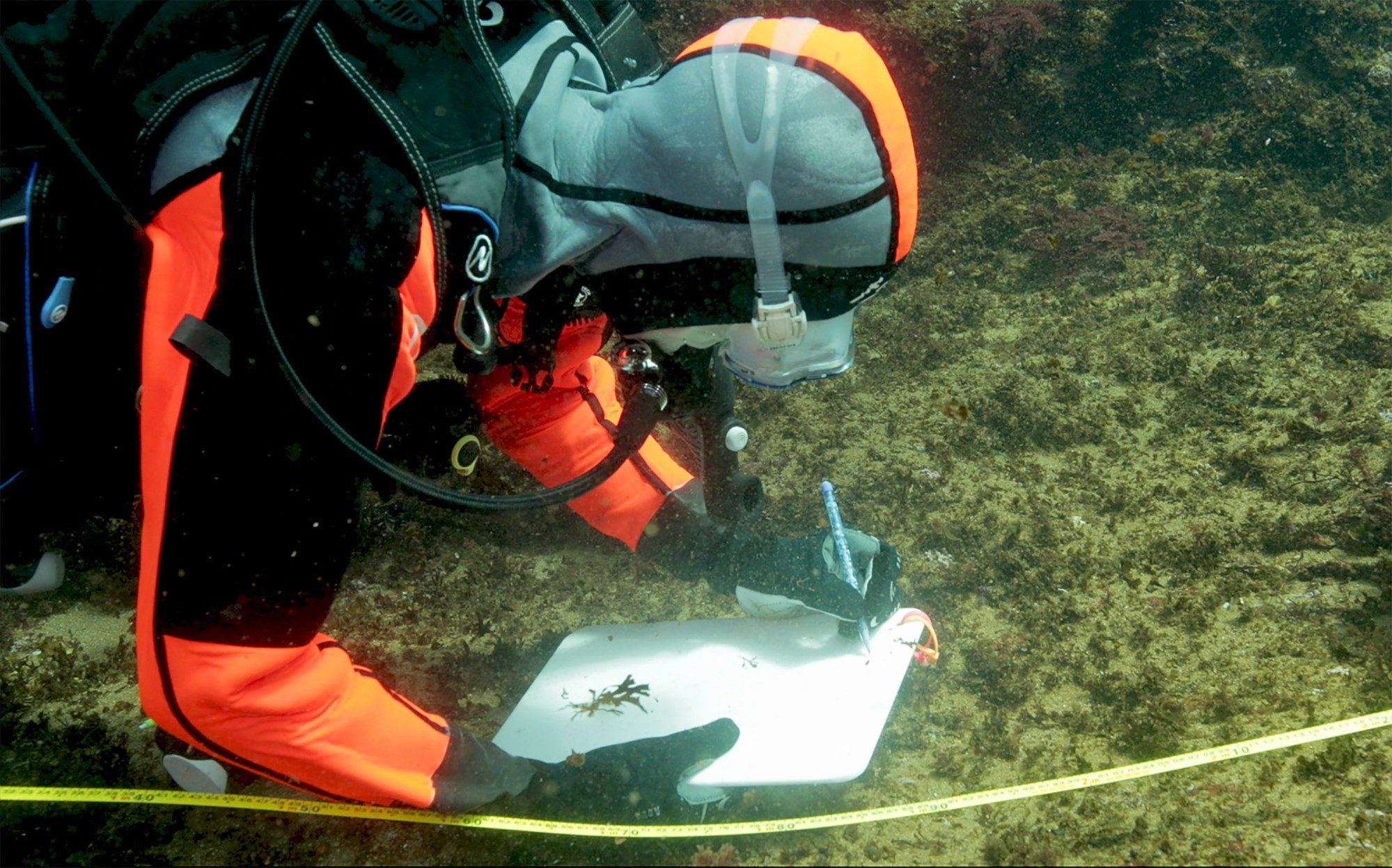

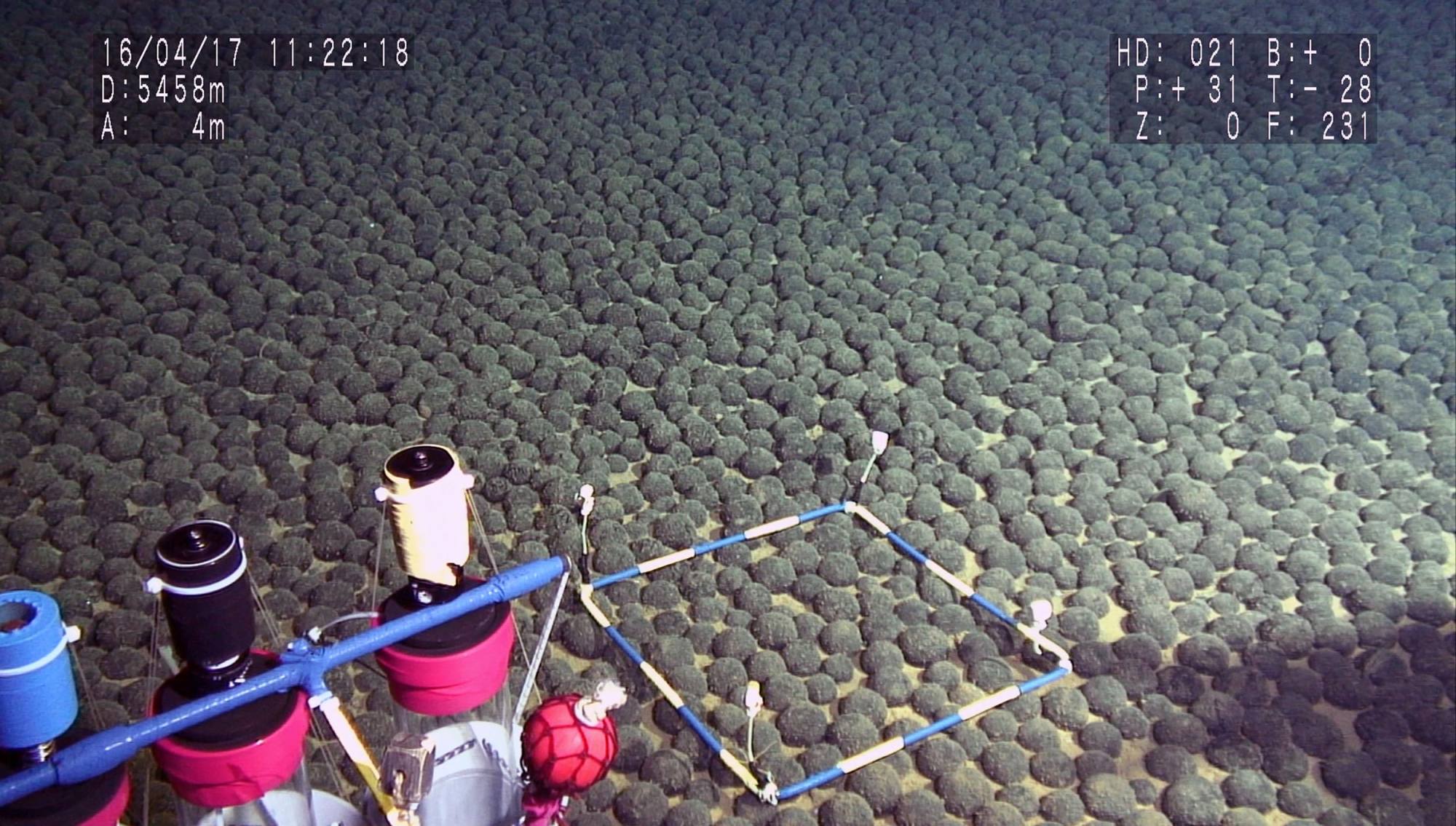

During the three-week operation, equipment will be lowered from the drilling ship Chikyu to around 5,500 metres (18,000 feet) to extract roughly 35 tonnes of seabed mud. While small samples have previously been collected from similar depths, the scale of this project is unprecedented, representing a step towards the commercial extraction and use of undersea minerals.

The recovered material will then be transported back to Japan, where it is hoped that each tonne of mud will yield an average of 2kg (4.4lbs) of rare earths.

Japanese researchers have already identified substantial mineral deposits in other waters within the nation’s exclusive economic zone. A 2018 study off the Ogasawara Islands, about 1000km (620 miles) south of Tokyo, suggested that a 400 sq km (154 square-mile) area could hold as much as 16 million tonnes of rare earths.

Scientists estimated that the site’s deposits of yttrium – an element used in the manufacture of displays, superconductors and lasers – alone could satisfy 780 years of domestic demand.

Major reserves of europium, terbium and dysprosium – used for high-performance magnets as well as defence and nuclear applications – were also discovered.

Japan’s drive to reduce its dependence on imported strategic minerals has been spurred on by concerns over economic security. Strained trade relations with the United States have prompted Tokyo to redouble efforts to source its own resources, while long-standing competition with China over rare earth access has added to the urgency.

Beijing has previously restricted or entirely halted rare earth exports to other nations, including Japan, to show its diplomatic displeasure.

But despite the apparent necessity, Tokyo’s plans have elicited deep concern from environmental groups, as well as the many Pacific island nations whose survival hinges on the health of the ocean.

In July 2022, the Federated States of Micronesia joined the Alliance of Countries for a Deep-Sea Mining Moratorium, launched at the United Nations Ocean Conference in Lisbon the previous month.

In a statement, then-president David Panuelo acknowledged that mining the Pacific for natural resources offered the promise of “significant wealth” but warned it could also “lead to the systemic collapse of our oceanic ecosystems, resulting in mass starvation and mass environmental destruction”.

Unhandled type: inline-plus-widget {“type”:”inline-plus-widget”}

Such outcomes would worsen the effects of climate change and bring about “abject economic suffering to peoples and communities who do not benefit from mining activities but feel their direct impacts”, he said.

Duncan Currie, an environmental lawyer advising the High Seas Alliance of like-minded nations and green groups, cautioned that without a moratorium, deep-sea extraction could have disastrous consequences.

“We know the ‘collector’ on the sea floor will dig into the sea floor up to 15cm (5.9 inches), releasing sediment plumes from disturbing the seabed,” he told This Week in Asia. “These plumes will likely travel considerable distances, possibly hundreds of kilometres, smothering life on and near the sea floor.”

Once commercial exploitation begins, processing is expected to take place aboard specialist vessels, with unwanted, toxin-laden sediment discharged back into the ocean.

Currie’s organisation recently wrote to the Japanese government, highlighting that while the US announced plans in April to exploit sub-sea resources in the central Pacific’s Clarion-Clipperton Zone, and the Canadian mining firm The Metals Company (TMC) has applied to operate there, such activities would violate the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the International Seabed Authority’s regulations, to which Japan is a party.

TMC has already identified Japan as a key processing hub for recovered polymetallic nodules, in partnership with Tokyo-based Pacific Metals Co for refining.

The letter warned that if nodules were illegally extracted and shipped to Japan for processing, the government would be breaching the UN convention, leaving Tokyo “open to legal action at both the national and international level”.

“We urge the government to take proactive action to censure any actor who seeks to undermine multilateralism, international law and both Japan’s and humankind’s best interests by pursuing unlawful deep seabed mining,” the letter read.

“I think public opposition to deep-sea mining is widespread and deeply felt,” Currie told This Week in Asia. “The challenge is in translating that opposition to the International Seabed Authority, and the danger is that the mining interests push through their agenda through legal machinations.”

“Seabed mining is highly legalistic, depending on international agreements, regulations and contracts and, once it is started, it will be extremely difficult to stop,” he added. “It will trigger a one-way race to the bottom of the sea: once the green light is given, such as through regulations, the new and damaging industrial activity will be under way.”