How Singapore’s early leaders supported Lee Kuan Yew’s vision by challenging him

Former Straits Times editor-in-chief Cheong Yip Seng reflects on the quiet candour and firm convictions of Singapore’s pioneer generation

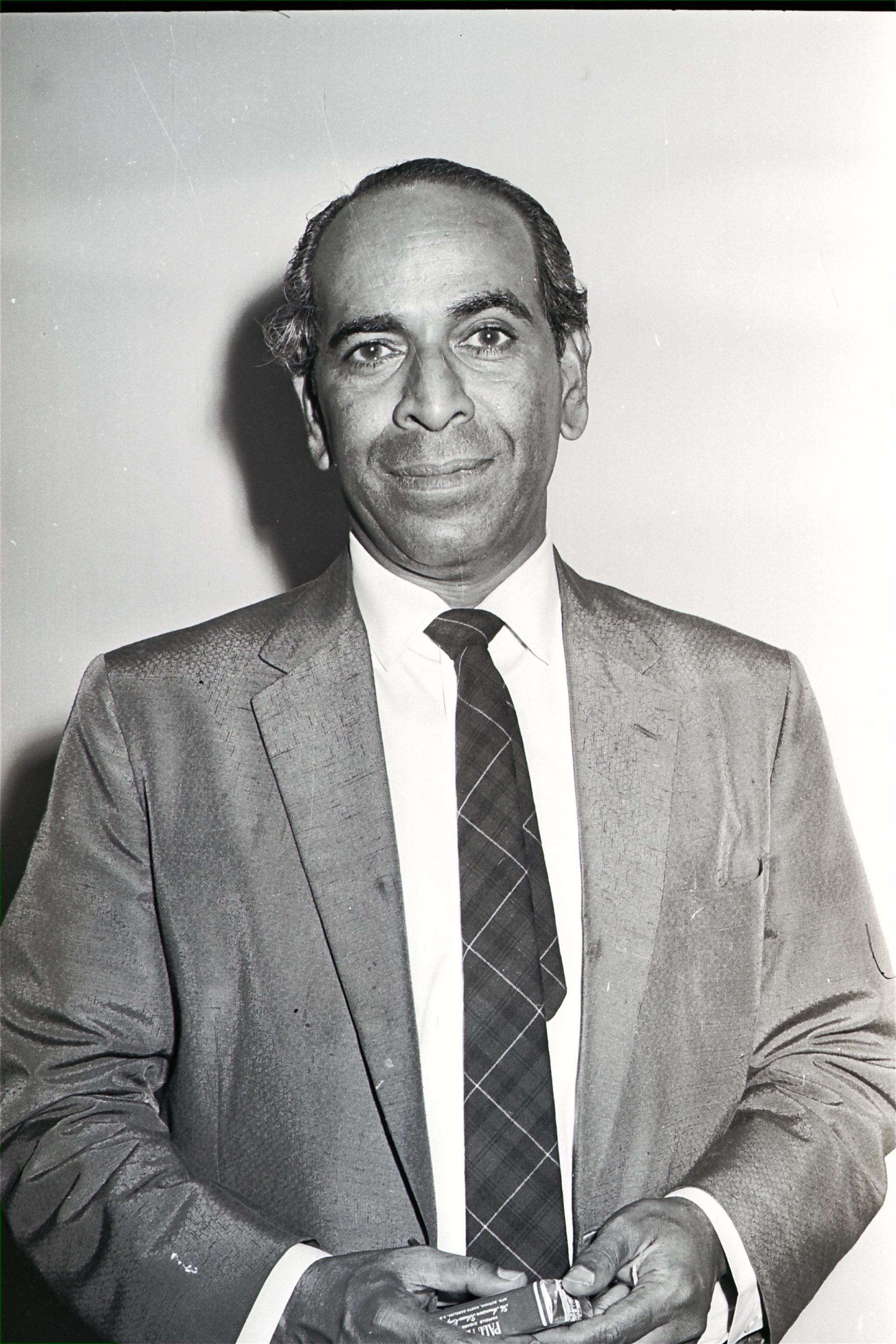

In this excerpt from Ink and Influence: An OB Markers Sequel, Cheong Yip Seng, former editor-in-chief of The Straits Times, offers rare behind-the-scenes insights into the personalities who shaped post-independence Singapore. Through stories involving figures such as S.R. Nathan, a senior civil servant who later became president, and S. Rajaratnam, the country’s first foreign minister, Cheong reveals a founding leadership team unafraid to challenge even Lee Kuan Yew – while remaining bound by a shared national mission.

A story S.R. Nathan once told me was revealing. He was S. Rajaratnam’s (Raja’s) Permanent Secretary when Raja took charge of the foreign ministry after Singapore separated from Malaysia. One afternoon, Raja was being interviewed by a visiting foreign correspondent, whose reporting was critical of Singapore.

S.R. received a call from Lee Kuan Yew’s (LKY’s) secretary: Can Raja drop by his office? Raja glanced at S.R.’s message, and carried on talking to his visitor. More than an hour went by. S.R. grew nervous. He didn’t think the Prime Minister should be kept waiting.

More time passed. LKY’s personal assistant was frantic and messaged S.R. again. S.R. sent a reminder, but Raja continued with the interview.

Late that afternoon, after the reporter had left, Raja phoned LKY. I was talking to a foreign correspondent, he told LKY. Did you want to see me? Never mind, was the reply.

S.R.’s point in narrating the story was to show how tightly-knit the team was. They were a group of equals drawn together by a common cause. It also showed how seriously senior leaders took the press, even those hostile to them.

Another story S.R. told me illustrated how the core team worked. In 1977, a Vietnamese plane was hijacked during a domestic flight from Saigon and landed at Seletar airport. The four hijackers wanted political asylum. S.R. was in charge of dealing with it. Negotiations dragged on. LKY was impatient, and phoned S.R. frequently for updates.

Dr Goh intercepted one call, and told LKY: “Leave him alone, he will call when he has something useful to report.” LKY did not bother S.R. again.

Lim Kim San (LKS) told me how he dealt with LKY’s impatience. He was then the Minister for National Development and LKY would regularly call the ministry’s Permanent Secretary for updates. LKS was furious, and called LKY.

He was direct: “If you keep doing this, you really do not need me here!” Then he put down the phone. LKY stopped calling the Permanent Secretary.

LKS was not a man to pull his punches. Although he was a member of the pioneer generation leadership, he had a mind of his own.

He had strong opinions, and was not afraid to air them in his chats with me. For instance, he disagreed with LKY on three major policies.

One, the reserves. He did not believe so much should be put aside for a rainy day. Central Provident Fund (CPF) contributors were a better judge of how much should be saved. After all, the money belonged to them. They knew better than the government how it could be used.

He believed it was impossible to prevent the reserves from being squandered by a future generation. Hence, there was no need for an elected president.

LKY was unmoved. In fact, he told me in private that if he had his way, he would lock up half of every worker’s salary in the CPF.

LKS believed the second key the president holds to protect the reserves was not foolproof. A future government could easily find ways around it.

Two, high ministerial salaries. LKS saw the negative consequences.

He felt strongly that political leaders wanting to serve should not be motivated by money. Also, not every minister truly deserves the high pay. Thirdly, the policy would drive up private-sector salaries. It would make Singapore too expensive, and encourage the wrong motivations.

Three, how the People’s Action Party (PAP) recruited political talent. LKS was known for his ability to size up people accurately, a rare gift. For years, he was the chief talent scout for the PAP, sitting through hours of interviews with potential candidates for elections.

“You really don’t need me for this,” he told the party. He felt the PAP’s selection criteria often resulted in the party picking the same type of people.

“It’s like a sausage machine,” he told me in exasperation. They all came out of the same mould.

He was candid, but only in private. His views were not for public consumption. He faithfully played by the rules that forbade publicly expressing views that were contrary to the government’s.

From these anecdotes, one could dispel the common myth that LKY was such a dominating presence there was little Cabinet debate. It was not true that LKY was not open to dissenting views. Whether he accepted them or not though, was another matter.

In the case of Raja, he and his Permanent Secretary, S.R. Nathan, worked closely together but S.R. practically ran the Foreign Ministry.

Raja, his minister, had little interest in administrative matters. He spent most of his time reading, meeting people, and thinking. An ideas man, he vigorously promoted them through his speeches.

It was a skill he honed as a political journalist for the now defunct Singapore Standard, and The Straits Times (The ST). It was he who drafted the Singapore Pledge and thought of Singapore’s future as a global city.

In fact, that was how LKY saw the future, a day after Separation on August 9, 1965. By developing itself as a hub for everything — maritime trade, aviation, logistics, finance — Singapore was linking up with the rest of the world.

Like the skilful wordsmith that he was, Raja gave it an inspiring name, “global city”, in a speech to the Singapore Press Club in 1972.

For someone so prescient, I was taken aback when I visited him after he retired from politics in 1988. He was in a tiny office at the Nanyang Technological University, as a distinguished senior fellow at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

I could not help thinking to myself that he was living in splendid isolation.

His wife had died in 1989 so he lived alone in a large house in Chancery Lane with two helpers. Surely, he must have known the risks of loneliness to his health, secluded away in his office in Jurong.

Would he write a book, I asked. He had been in the thick of things, one of a handful who intimately knew how the nation was born, and its struggles. More than that, he was an accomplished writer, and had published short stories and radio plays in the 1940s and ’50s.

In 2011, Epigram published all his works with an introduction by his biographer, Irene Ng, a former colleague and later PAP Member of Parliament.

Yes, he would write, Raja said, but it would not be the Singapore Story. He was more ambitious. He had been fascinated by the migration of people across the whole of Asia over the centuries. Not surprisingly, nothing came of it.

He did write, however. He became a frequent contributor to the Forum page of The ST. He used a pseudonym: One-legged chicken. Sometimes, he signed off as a two-legged or three-legged chicken. I cannot recall any memorable letters. But their overall tone was unmistakable. They all took tiny potshots at the government.

LKY was not amused. He knew the “chicken” was Raja, the style was so obvious. He sent word: Spare Raja the ignominy. I could not bring myself to stop Raja. My colleague, Leslie Fong, found the perfect solution. He decided the paper would no longer allow readers to use pseudonyms when writing to the Forum page.

Though Raja did not write his Singapore Story, Irene Ng did. Her two volumes on the man were the best books on modern Singapore history that I have read, after those of LKY.

The only other pioneer leader who wrote for The ST after retirement was Dr Goh, who asked me, after he retired from politics in 1985, if I would use op-ed pieces from him.

He wanted $5,000 a piece. Of course! I replied. With his intellect, experience, and writing skill, he would be a breath of fresh air. He wrote largely about economic issues. But he managed no more than half a dozen pieces. I did not ask him why he stopped. I know it is hard to sustain quality once you are out of the loop.

Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) was to be the last career move for LKS. He had one condition: a free hand. It was a point he repeatedly stressed to me on arrival.

The first letter of appointment, as SPH chairman, disappointed him. LKS rejected the offer which came from the SPH board. He refused to be just a figurehead.

He insisted on being executive chairman. He got his way.

The cost-cutter

I worked closely with him, and had a close-up view of the leadership style of this pioneer generation leader. On arrival in September 1998, he left no one in any doubt that, like LKY, he preferred to be feared than loved.

Not every editor could accept that style. Senior editors of my division in SPH met every weekday evening for what we called “coffee breaks”. It was a forum to make editorial decisions and discuss the latest run-in with the government.

For a few months after LKS’s arrival, I had to regularly soothe ruffled feathers as the editors would let fly at coffee break. They were fuming over what they considered the unreasonable conduct of the new boss, especially the way he treated some of the senior management staff.

Within months, he overhauled the team. This was one way he changed the team:

From their initial interactions with LKS, they would get a good idea how they were regarded. In one case, the person asked LKS, “Am I in your plans?” When the hapless man got his answer, he sent in his notice.

In the end, CEO Frank Yung and about six or seven others left.

I laid all my cards on the table. I invited him to join all my meetings with the editors so he could see for himself how the newsroom was run. For the first few Saturdays of his arrival, he kept tabs on me by calling me on the phone. He wanted to know what was keeping me busy.

After a few months, he decided it was enough. “I leave it (the job) to you,” he said. Making editorial judgments every day under deadline pressure was not his cup of tea. From then on, I got a free hand.

He never interfered in newsroom operations. Not once did he tell me how a sensitive story should be handled. The only red line he drew was over coverage of his family business, Mothercare, the shop catering to infant needs.

His political stature was a huge asset. Once, he showed me a letter he received from LKY.

After I read it, he asked: “What do you think?” LKY was asking him to remove one of the editors, who was regarded by some members of the Cabinet as a thorn in their side.

When I said I had no reason to accede to the request, he was silent. But only for a few moments. Then he filed the letter away. We did not hear from LKY again on this matter. Nor did I ask how LKY reacted to my response.

On another occasion, LKS gave me feedback from LKY, who told him that some of our writers were too critical of the government. My response: How do I retain talent if the writers were not given space to air their views?

He took the point. And the matter rested.

He was also largely focussed on corporate matters. He rewarded staff, giving them SPH shares which peaked at $38, before the share split.

LKS was the second of three executive chairmen sent to SPH during my time, basically to act as a monitor, build trust between the newspapers and the government, and ensure the editors did not consistently stray beyond the OB markers.

The first was S.R. Nathan, then Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Ironically, he had been SPH’s choice. In 1982, The ST’s relations with LKY had soured so much, he decided he would move in a team from the civil service.

LKY had been inspired by the success of a civil service team he had sent to revamp the chaotic public transport system. Before 1973, there had been as many as 11 bus companies plying the roads. But the system was in shambles. Breakdowns were frequent and buses were poorly maintained. The civil servants consolidated the industry and made changes that vastly improved public transport.

Months before S.R. came, LKY had several rounds of meetings with then CEO Lyn Holloway and editor-in-chief Peter Lim. They met on Saturday afternoons at his Istana office, in a bid to find a way to deal with LKY’s loss of confidence in The ST.

Little came of it. LKY could not be dissuaded, but he could compromise. He agreed to the newspaper’s choice of S.R as monitor.

Excerpted from Ink and Influence: An OB Markers Sequel by Cheong Yip Seng, published by World Scientific Publishing. Cheong also served as an editorial adviser to the South China Morning Post.